When I was a lad, the environmental movement was dead set against pollution taxes. Robert N. Stavins and Bradley W. Whitehead said in 1992:

…for many years, market-based incentives were characterized by environmentalists, not only as impractical, but also as “licenses to pollute.” Over time, environmental groups have frequently applied a different and more rigorous standard in measuring market-based systems against their command-and-control counterparts, possibly because of their belief that market-based systems legitimize pollution by purporting to sell the right to pollute. This old suspicion likely continues among many rank-and-file environmentalists.

How times have changed. Now the environmental movement of the biggest champions of carbon taxes as well as carbon trading. What gives? Anything more than cynical political opportunism? Concede nothing until the last moment when it is tactically opportune to sideline opposition.

Initially, all environmental regulations were command and control regulations that specified quantities and the technologies to be mandated and gave no role to prices to ensure that the pollution reduction was done by those who could do it cheapest. Robert Crandall noticed the shift in position in his recent essay on pollution controls:

… environmentalists have increasingly realized that markets can work to allocate pollution reduction responsibilities efficiently among firms and across industries. Although the command-and-control approach is still the norm, environmental lobbyists and legislators have, on occasion, considered market-based approaches to pollution control. Most of the proposals for limiting global warming, for example, explicitly include market-based approaches for controlling carbon dioxide emissions.

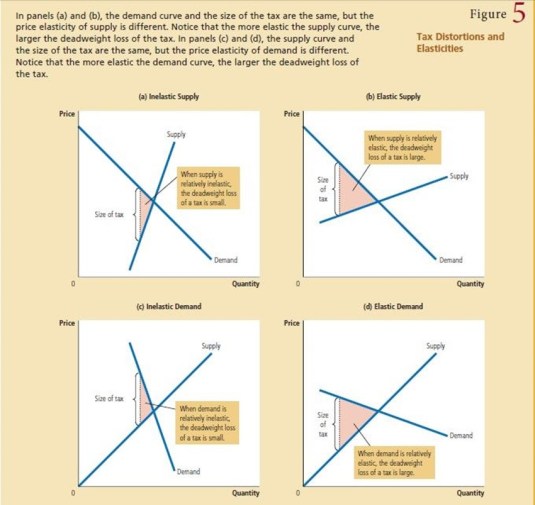

The reason for the change in tactics by the environmental movement is quite straightforward. The deadweight cost of regulation and taxes that leads to increasing resistance from those subject to existing and proposed environmental regulations.

- The deadweight losses of taxes, transfers and regulation are a constraint on inefficient policies (Becker 1983, 1985; Peltzman 1989).

- The deadweight loss is the difference between winner’s gain less the loser’s losses from a tax or regulation-induced change in output. Changes in behaviour due to taxes and regulation reduce output and investment.

- Policies that significantly cut the total wealth available for distribution by governments are avoided because they reduce the payoff from taxes and regulation relative to the germane counter-factual, which are other even costlier modes of redistribution (Becker 1983, 1985).

The rising deadweight cost of regulation due to technological change, and the dissipation of wealth through these rising costs progressively enfeebled environmental groups lobbying for more regulation. This allowed industry and consumers to win the initiative in resisting more environmental regulation. The cost of reducing carbon emissions is a classic example. Another is the United States acid rain allowance market.

In the case of carbon emissions, the additional political pressure that the winners had to exert to keep the same reduction in carbon emissions had to overcome rising pressure from the losers such as carbon intensive industries and they consist customers to escape their escalating losses of complying with any sort of further carbon emission regulation.

Eventually, the fight was no longer worthwhile relative to the alternatives. Taxed, regulated and subsidised groups can find common ground in wealth enhancing policies and an encompassing interest in mitigating any reduction in wealth from public policies (Becker 1983, 1985; Peltzman 1989).

In the case of global warming, both the environmental movement, and carbon intensive industries, and consumers find common ground in finding a cheaper way of reducing carbon emissions. That is done by agreeing to either carbon trading or carbon taxes. Coalitions of environmentalists and industry also form where carbon emission taxes or trading disadvantage the competition of some industries and some competitors within the same industry.

Carbon trading was a classic example of these dark coalitions. There’s a big difference in their cost to industry depending on whether carbon trading quotas are auctioned or given away to the incumbent firms for free or at a discount price.

Recent Comments