The Government’s offer to pay half the 2007 rateable value to uninsured properties and bare land in Christchurch’s ‘red zone’ has been declared unlawful and the Crown has been asked to reconsider, in a split decision by the Supreme Court.

The most important task for governments after a natural disaster is to uphold the basic rules of the game: private property rights, contracts made prior to the disaster and the rule of law and also repair and restore the infrastructure services that governments own.

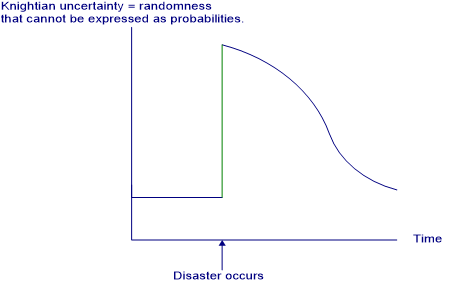

There is a massive spike in Knightian uncertainty after a natural disaster. Knightian uncertainty is risk that cannot be calculated. Risk usually means a quantity susceptible of measurement. Risk applies to situations where the outcome of a given situation in known, but we can accurately measure the odds. Risk can be insured against because the probabilities of underwriter loss are known in advance. Knightian uncertainty is radically distinct from this more familiar notion of risk and applies to situations where we do not know enough information in order to set reliable odds in the first place.

Knightian uncertainty after a disaster spikes because so many things change so quickly and cannot be calculated. The level of damage is unknown as is the amount of surviving resources and how people are adapting to the situation and their plans for the future. This extreme uncertainty continues in a short period due to the continued lack of new knowledge and the confusion under the chaotic situation created by the natural disaster.

The length of this period of extreme uncertainty depends on the size of the natural disaster and the extent of the damage. As the emergency response and recovery takes hold, more is known about damages, surviving resources, disaster relief requirements and recovery and rebuilding needs now and into the future. Thus the degree of Knightian uncertainty will diminish after the disaster by the falling away of uncertainty after the initial spike at the time of the natural disaster.

To the extent that governments must adjust rules of the game pertinent to the rebuilding process, such adjustments must respect property rights and the rule of law, and must be made quickly, clearly, and credibly. If governments draw out the decision-making process about rules of the game, the signals that civil and commercial society receives are likely to become noisy and the resulting uncertainty will delay the rebuilding process. The aim of the government is to reduce Knightian uncertainty after a natural disaster, not increase it.

After disasters, the pre-existing knowledge discovery, handling and dissemination capabilities of government do not improve. The merits of government and the market process must be compared ‘warts and all’ in disaster response and recovery. Disaster response and recovery requires quick adaptation and fast learning about the nature of rapidly unfolding and confusing events. A great merit of the market process in normal times and after natural disasters is how little the individual participants need to know in order to be able to take the right action.

Legal frameworks need to change to remove barriers to governments and the market process to allow rapidly adaptation of people and resources to the post-disaster circumstances and learning and adjusting quickly.

The decision of the Supreme Court to require the NZ government to reconsider its settlement offer to landowners is an example of the regime uncertainty that undermines natural disaster response and recovery in Christchurch after the 2011 earthquake.

Regime uncertainty is a situation where the government increasingly undermines public trust in the durability of private-property rights and the rule of law. Without the assurance that the government would abide by and enforce these rules, entrepreneurs and investors remained on the side-lines, stalling the post-disaster recovery. The signals on which people depend to make decisions become difficult to read if there is also noise in the information they collect due to irrelevant, false and misleading factors.

Disaster-relief policies and regime uncertainty can be sources of this noise. Signal noise distorts the market prices that guide private sector adjustments to the new circumstances after the natural disaster. Uncertainty about the rules of the game inhibits the ability and willingness to reinvest and anchors expectations around pessimistic post-disaster outcomes.

The best way policymakers can avoid problems of regime uncertainty in the aftermath of a disaster is to respect and continue to enforce private property rights and the rule of law and uphold contracts made prior to the disaster. To the extent that the government decides to adjust rules pertinent to the rebuilding process, such adjustments must respect private property rights and the rule of law. Furthermore, such rule changes must be made quickly, clearly, and credibly. If policymakers draw out the decision-making process, the price signals that civil and commercial society receives are likely to become noisy and less useful to those who are rebuilding.

This decision of the Supreme Court to overturn a key government decision prolongs regime uncertainty for several more years and invites further litigation.

After the initial emergency relief period, the principal roles of government in disaster response and recovery are guaranteeing that the rules of the games have not changed and the repair and restoration of public infrastructure services.

Whatever benefits government disaster relief and interventions might bring, these benefits must be weighed against the potentially costs imposed by the introduction of signal noise over what might happen in the future and what is happening right now to the rules of the game.

As communities emerge from the immediate crisis and set out on the road to recovery, this regulatory trade-off over regime uncertainty is increasingly relevant. The decision today of the Supreme Court of New Zealand illustrates this point in spades.

A leading advantage of government in a recovery from a natural disaster is its ability to compel people to make exchanges. Compulsion overcomes the hold-out problem and deals with new and modified externalities and with some unusual post-disaster co-ordination problems. The government made a major mistake not making the offers in terms of the sweeping emergency powers past just after the 2011 earthquake.

Recent Comments