Regional development policies have a long history as a way of pretending to rescue a region from decline. These days, regional development policies are known as place making policies. Place making policies range from the old-fashioned regional development policy of days gone by to enterprise zones and export zones:

Place-based policies refer to government efforts to enhance the economic performance of specific areas within their jurisdiction. Most commonly, place-based policies target underperforming areas, such as deteriorating downtown business districts in the United States or disadvantaged areas in European Union countries. But they can also be designed to improve the economic performance of areas that are already doing well, for example by encouraging further development of an existing cluster of businesses concentrated in a particular industry.

Regional development policies have multiple effects. This blog post will focus on those related to employment. The reason is that regional development policies are back in the news in New Zealand because of the by-election in a northern part of New Zealand that is in decline.

The research into regional development policies has one thing going for it. Regional development policies are subsidies. If you subsidise something, upwards sloping to supply curves being what they are, you usually see more of whatever is subsidised.

The twist in the tale is that you’re not actually attempting to subsidise the industries and firms who are the recipient of the subsidies under a regional development policy. You attempting to encourage activity in in a particular region to the benefit of their employment of the existing residents. More jobs and better paid jobs for the existing residents of an area in decline such as Northlands in New Zealand.

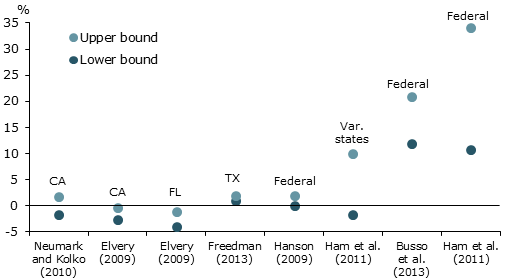

Source: David Newmark and Helen Simpson (2015).

The evidence on the employment effects of regional development policies is rather mixed as shown by the graph. A lot of the studies seem to be clustered around zero. One of the reasons why regional development policies are unsuccessful for the existing residents of the region lies in another result of studies of regional development policies:

…there is consistent evidence of housing price increases, implying that benefits are received by unintended recipients

The reason why housing prices are increasing is outsiders move to the region to take the jobs created by the industries are being subsidised within the region pursuant to the regional development policy. The local workforce benefits only in a minor way in terms of new job opportunities and ends up paying higher rents. The only clear winners among existing residence of homeowners. One of the few saving graces of declining regions is that the housing prices fall quite significantly because as a durable stock that has nowhere else to go.

It doesn’t matter much whether the regional development policy was aimed at subsidising jobs for high skilled or low skilled workers. The inflow of workers from outside the whatever skill level it may be is a pretty consistent finding.

New Zealand is a small country with a highly integrated labour market. No place in New Zealand is more than 80 km from the sea. Is relatively easy to move into regional New Zealand, especially now that housing prices are so high in Wellington and in Auckland in particular.

Inter-regional migration is the predominant channel of regional labour market adjustment in New Zealand, although unemployment and labour force participation also play supporting roles (Choy and Maré 2002).

Changes in wages have been found to account for very little of regional labour market adjustment. The inflow and outflow of workers is rapid, inside a few years, in response to a shift in regional labour demand in New Zealand (Choy and Maré 2002; Grimes, Maré and Morton 2009). These New Zealand findings are consistent with those overseas showing that the dominant effect of a local labour market shock is migration. People moving in and out as labour opportunities fluctuate.

The rapid speed of regional labour market adjustment will undermine any regional labour demand policy (Choy and Maré 2002). New workers will migrate into expanding regions quickly, filling an estimated half or more of the new jobs in a New Zealand region and local wages will not increase by much, but local housing costs may come under upward pressure (Grimes, Maré and Morton 2009).

When there is an adverse regional demand shock, housing prices drop precipitously because the regional stock of housing is durable. Housing prices quickly fall well-below new construction costs. The excess in capacity also drives down rents. There is evidence that some low paid workers and welfare beneficiaries remain in or migrate to declining regions because of an abundance of cheap housing and lower living costs. There is already a Work and Incomes policy that discourages beneficiaries from moving to areas of limited economic opportunity.

The OECD (2005) found evidence that programmes that target high-unemployment regions can lock workers into low-paid jobs in these depressed regions. The public provision of a local job can reduce regional mobility and the intensity of job search. This lock-in effect leads us to the answer for declining regions that was explained well when by Edward Glaeser when he was discussing rebuilding New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina:

For too long, America’s declining cities have tried to find magic bullets that would bring them back to their former glory. Eighteen months ago, I suggested that Buffalo wasn’t about to come back any time soon. I argued that would be far wiser to accept the reality of decline and focus on investing in human capital that can move out, not fixed physical capital. After all, the job of government is to enrich and empower the lives of its citizens, not to chase the chimera of population growth targets.

Just once, I want to hear a Rust Belt mayor say with pride “my city lost 200,000 people during my term, but we’ve given them the education they need to find a better life elsewhere.” Urban decline is a reality in much of older, colder America.

This is a great point. Is the purpose of a Government to look after those who will stay behind or to promote the interests of everyone, including those planning to emigrate? In the case of regional economic development policies, they are funded by higher tiers of government, such as the national government responsible for looking out for everybody.

Recent Comments