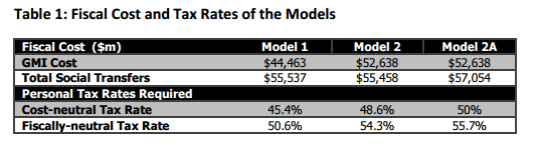

The Treasury modelled a Guaranteed Minimum income (GMI) at the request of the Welfare Working Group in 2010. A GMI paying $300 per week – the mean benefit income among those on benefits – would cost $44.5 billion (model 1) or $52.6 billion if we extended it to super annuitants as a replacement for NZ Superannuation or old age pension (model 2). The former could be covered by a flat personal income tax rate of 45.4%; the latter, 48.6%.

Full fiscal neutrality would require tax rates of 50.6% and 54.4% – the lower tax rates would be just enough to cover the transfers, but income tax revenues are currently also used to fund more than just transfers.

If we recognize that most parents are beneficiaries via Working for Families and compensate them for their loss with a $86 per child per week payment (model 3), we get a $57.1 billion fiscal cost and a personal tax rate of 50% (or 55.7% for fiscal neutrality).

Treasury noted that many beneficiaries (including the disabled, carers and sole parents) currently receive more than $300 per week and would be made financially worse off under a GMI scheme.

Treasury also warned about potential adverse labour supply responses to the necessary higher personal income tax rates. The large gap between company and personal tax rates would increase IRD’s enforcement costs.

In 1987, Finance Minister Roger Douglas announced a Guaranteed Minimum Family Income Scheme to accompany a new 22% flat income tax. The idea did not go ahead.

Richard Nixon also proposed a guaranteed minimum family income plan in 1969 to replace the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AIDC) scheme at the behest of future Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. This was based on the negative income tax proposals of Milton Friedman and George Stigler. Nixon’s plan passed the House but not the Senate after 3 years of infighting.

The final outcome was the earned income tax credit (EITC) in 1975 that was expanded significantly in the 1990s to become the largest single federal income transfer programme. One attraction of the EITC is that because its benefits rise positively with earnings up to the phase-out point, so it can have a positive rather than negative effect on work incentives for workers on a low wage.

Recent Comments