I was chatting with a friend in the pub the other night about the proliferation of contractors in New Zealand in the government sector. It was observed that many of them simply perform the jobs of employees and bring no special skills for them but are very expensive to hire. They are paid a premium because that they are supposedly hired on short notice for short periods of time to fill gaps. They are paid a premium for their availability and willingness to leave on short notice without fuss.

I had no experience of contractors in Australia. If a gap needed to be filled within an agency quickly, you went to a manager higher up the hierarchy. The decision was made then to reallocate through secondments staff from another part of the agency from an area that was less busy than normal at the moment. In the interim, staff are recruited to fill any gap that is anything more than short-term with the secondments filling the gap until the recruits arrive.

Will you ask @WoodhouseMP to end zero-hour contracts for good? They're unfair and wrong. nzlp.nz/0hrspk http://t.co/IB8rm0gu6w—

New Zealand Labour (@nzlabour) April 09, 2015

The conversation then turned to the issues as to why any employees are guaranteed a minimum number of hours or continuity of employment. Why isn’t everyone on a zero hours contract and only come in when they are needed and are paid accordingly.

We've had 900+ submissions on the Employment Standards Legislation Bill so far. Submit here: responses.psa.org.nz/subesl20150916… http://t.co/XzIiiMYgOD—

(@NZPSA) September 24, 2015

The reason for long-term employment agreements with fixed hours and weekly wages irrespective of how busy the business is arises from the fixed costs of employment, and the costs of search and matching in the labour market.

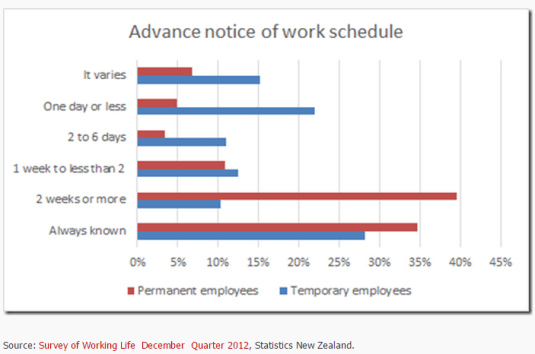

The difference between zero hours contracts and permanent employment may be a overstated. Advance notice of work schedules is always known only to a minority of temporary and permanent employees in New Zealand. There is not much difference between that advance notice between temporary and in permanent employees.

Critics overplay their hand if they suggest that somehow workers a very much disadvantaged and employers are holding all the cards. Job turnover and recruitment problems are a serious cost to a business. Workers will not sign contracts, such as zero hours contracts or casual work contracts if they are not to their advantage.

The question that must always be asked is why do people who are deemed competent to vote and drive cars sign zero hours contract? What is in it for them? David Friedman asked this question about the economics of restraint of trade agreements for employees:

…the employer who insists on an employee signing a non- competition agreement will find that he must pay, in additional wages or other terms of employment, the cost that the agreement imposes upon the employee, as measured by the employee and revealed in his actions. It follows that the employer will insist on such an agreement only if he believes that its value to him is greater than its cost to the employee… The contract is designed, after all, with the objective of getting the other party to sign it. If I am designing the contract and offering it to many other parties, that may put me in a position to commit myself to insisting on terms that give me a large fraction of the benefit that the contract produces. But it is still in my interest to maximize the size of that net benefit-which I do by only insisting on terms that are worth at least as much to me as they cost the other party.

Critics overplay their hand if they suggest that somehow workers are very much disadvantaged and employers are holding all the cards. Job turnover and recruitment problems are a serious cost to a business. Workers will not sign zero hours contracts if they are not to their advantage.

Unless labour markets are highly uncompetitive with employers having massive power over employees, employers should have to pay a wage premium if zero-hour contracts are a hassle for workers.

The fixed costs of employment are such that you shouldn’t expect zero-hour contracts: you’ll typically do better with one 40-hour worker over two 20-hour workers because of these costs. Zero hour contracts would be most likely in jobs with low recruitment costs and where specialised training needs are low. Workers with low fixed costs of working will move into the zero-hour sector while those with higher fixed costs would prefer lower hourly rates but more guaranteed hours. Again, read lower here as meaning relative to what they could elsewhere earn.

This is what 1599 submissions against the Employment Standards Legislation Bill looks like. http://t.co/WrkGpIiOP2—

(@NZPSA) October 06, 2015

Most workers, the majority of workers are on conventional employment agreements. They work five days a week, 40 hours a week for a fixed pay.

Anyone I know who decides to work as a contractor expects to be paid much more than a conventional employee. They command a large premium for not having certainty of hours and ongoing employment. The same goes for any job that is particularly risky, has unsocial hours or involves weekend work or anything else that departs from the standard working week. All these jobs command a wage premium.

Employers incur fixed costs of employment when they recruit and train new employees. These recruits must be expected to stay long enough to work sufficient hours for the firm to expect to recover these investments [Oi (1962, 1983a, 1990), Idson and Oi (1999), Hutchens (2010), Hutchens and Grace-Martin (2006)].

These costs are fixed costs because they do not vary with how many hours the employee works or with how long an employee stays with their employer. On-going supervision, office space and other overheads can increase with the number of employees, not the hours they work per week. These fixed employment costs must be recouped over the expected job tenure of the employee with the firm.

Employers will not hire an additional worker unless they anticipate recovering the costs of doing do including fixed employment costs and other overheads.

Hiring one more worker for 40 hours per week is cheaper than hiring two workers to work 20 hours per week each. These two part-timers would about double the recruitment and training costs to secure the same total additional supply of hours worked per week. Profits are a small share of the revenue earned on selling the output of each worker.

Zero hour contracts would be most likely in jobs with low recruitment costs and where specialised training needs are low. Workers with low fixed costs of working will move into the zero-hour sector while those with higher fixed costs would prefer lower hourly rates but more guaranteed hours. Again, read lower here as meaning relative to what they could elsewhere earn.

The literature on the economics of the fixed costs of work arose out of the economics of retirement and the economics of the labour supply of married women, and in particular of young mothers. This literature was attempting to explain why older workers, or young mothers either worked a minimum number of hours, or not at all.

Fixed costs of working constrain the choices that employees make about how many hours and days that are worthwhile working part-time. For employees, the fixed costs of going to work limit the numbers of days and number of hours per day that a worker is willing to work part-time. The timing costs of working at scheduled times and a fixed number of days per week can make working fewer full-time days, rather than fewer hours per day less disruptive to the leisure and other uses of personal time.

The fixed costs of working induced older workers to retire completely, and young mothers to withdraw from the workforce for extended periods of time, unless these workers worked either full-time or enough hours part-time each day and through the week to justify the costs of commuting and otherwise disrupting their day and week.

There are fixed costs to workers and employers finding each other as a suitable job match. They commit to a long-term relationship rather than risk that good job match dissolving and they are not able to recruit the fixed cost of initially finding such a good match.

Employers choose not to lay off workers during recessions because they want to retain their job specific human capital and recoup the fixed costs of employing them. If the employer lets them go in a downturn that is mild, they risk having to spend considerable money on finding our suitable replacement down the road.

It’s costly for employers to lose good employees. It’s equally costly for them to find good employees and quickly lose them again because they are unhappy or not as well-paid as elsewhere. There is much to be made on both sides of the employment relationship through long-term relationships. That’s why not everyone is on a zero-hours contract.

Zero hours contract doesn’t make it any cheaper for an employer to find a suitable recruit then train that recruit. A wage premium must be paid to induce the would-be recruit to prefer that working arrangement with no fixed hours over the others available to them including staying in their existing job.

Regulation of zero hours contracts will deny workers the option of higher wages by accepting uncertain hours. Hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders already work on employment agreements where there hours are not fixed but a variable on relatively short notice.

Recent Comments