When I was studying in Japan, they were at the end of phasing out working on Saturdays. The staff at my university work on Saturday mornings for four hours and then went home.

The Japanese working week was reduced by law from 48 to 44 hours per week in 1988 and to 40 hours per week from 1993 (Prescott 1999; Hayashi and Prescott 2002). The Japanese stopped routinely working on Saturdays over the 1990s. The number of national holidays was increased by three and an extra day of annual leave was also prescribed by law.

While feuding with strangers on an unrelated matter about the gender wage gap, it somehow occurred to me that the six-day working week might have something to do with what is on the face of a large amount of sexism in Japan and a large gender wage gap.

That feud with strangers was about unconscious bias as a driver of the gender wage gap in New Zealand. The gender wage gap Japan is attributed to conscious prejudice.

Source: OECD Stat.

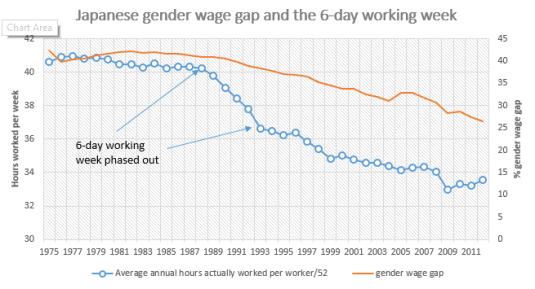

In the above chart I have plotted the average weekly hours worked of Japanese workers and the Japanese gender wage gap. Two things can be noticed from the above chart:

- there is a sharp reduction in the number of hours worked per week by Japanese workers when they stopped working on Saturdays; and

- the gender wage gap started declining after the introduction of a five-day working week in Japan.

In a country where it is standard to work six days a week, the price of motherhood would be much higher than in other countries industrialised countries that phased out the 48-hour week decades previous. The asymmetric marriage premium would also be much higher if one partner to the marriage worked a six-day week while the other looked after the children.

Other drivers of the gender wage gap that arise from human capital specialisation and depreciation and from the differences of a few years in the marrying ages of men and women would be intensified if people worked another day per week. The payoff from a marital division of labour and human capital specialisation where one worked long hours and the other focused on investing in human capital that allow them to care for the children and move in and out of the workforce with less human capital depreciation would be much larger.

Much is made of the distinctiveness of Japanese culture and its sexism. In my time in Japan, the thing I notice most distinctively about Japanese culture was its extraordinary pragmatism and willingness to change rapidly. The Japanese economic miracle was founded on rapid industrialisation, innovation and repeated renewal of human capital. That requires an entrepreneurial spirit and open-mindedness.

Cultural and preference based explanations of the gender wage Including that in Japan underrate the rapid social change in the role of women in the 20th century in all countries in all cultures. As Gary Becker explains:

… major economic and technological changes frequently trump culture in the sense that they induce enormous changes not only in behaviour but also in beliefs. A clear illustration of this is the huge effects of technological change and economic development on behaviour and beliefs regarding many aspects of the family.

Attitudes and behaviour regarding family size, marriage and divorce, care of elderly parents, premarital sex, men and women living together and having children without being married, and gays and lesbians have all undergone profound changes during the past 50 years. Invariably, when countries with very different cultures experienced significant economic growth, women’s education increased greatly, and the number of children in a typical family plummeted from three or more to often much less than two.

A good explanation of this rapid social change is in Timur Kuran’s “Sparks and Prairie Fires: A Theory of Unanticipated Political Revolutions” and “Now Out of Never: The Element of Surprise in the East European Revolution of 1989“.

Kuran suggests that political revolutions and large shifts in political opinion will catch us by surprise again and again because of people’s readiness to conceal their true political preferences under perceived social pressure:

People who come to dislike their government are apt to hide their desire for change as long as the opposition seems weak. Because of the preference falsification, a government that appears unshakeable might see its support crumble following a slight surge in the opposition’s apparent size, caused by events insignificant in and of themselves.

Kuran argues that everyone has a different revolutionary threshold where they reveal their true beliefs, but even one individual shift to opposition leads to many others to come forward and defy the existing order. Small concessions embolden the ground-swell of revolution.

Those ready to oppose social intolerance or who are lukewarm in their intolerance keep their views private until a coincidence of factors gives them the courage to bring their views into the open. They find others share their views and there is a revolutionary bandwagon effect.

Plenty of people have had personal experiences of this in the 1980s and the 1990s when there were rapid changes in social and political attitudes about racism, sexism and gay rights. This includes Japan.

In the case of the Japanese gender wage gap, the move from a six-day to a five-day working week radically changed the asymmetric marriage premium and the payoff from investing in both specialised human capital and in human capital that depreciates quickly when away from work.

This large shift in incentives to work and invest in human capital would embolden a change in social attitudes. This is because the previous views were no longer profitable and many would gain from the change. Others who prefer just to go along with crowd would quickly follow them in to stay in tune with whatever is now popular.

Much of Japanese sexism may be the preference falsification that was low-cost when there was a six-day working week. The move to a five-day working week greatly increased the cost of that sexism and the profits from finding new ways of organising the workplace that better matched motherhood and career in Japan.

Undervalued workers are an untapped business opportunity for more alert entrepreneurs to hire these undervalued workers. In the case of Japan, with a five-day working week, hiring women for jobs that involved considerable investment in firm-specific human capital became more profitable. Previously under a six-day working week it was more profitable to invest in men because they undertook few childcare responsibilities. Under a five-day working week, that payoff matrix favours women more than in the past.

Recent Comments