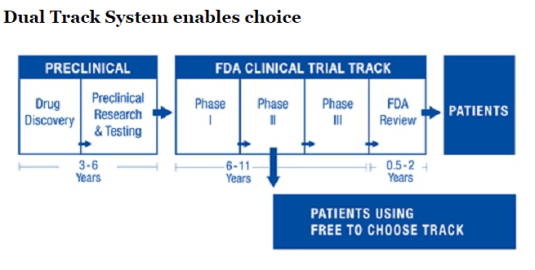

Bart Madden and Vernon Smith outlined a brilliant proposal charted above to shorten lags in the availability of life-saving medicine based on reforms in Japan:

Recently, Japanese legislation has implemented the core FTCM [Free to Choose Medicine] principles of allowing not-yet-approved drugs to be sold after safety and early efficacy has been demonstrated; in addition, observational data gathered for up to seven years from initial launch will be used to determine if formal drug approval is granted. In order to address the pressing needs of an aging population, Japanese politicians have initially focused on regenerative medicine (stem cells, etc.).

Source: Give The FDA Some Competition With Free To Choose Medicine – Forbes via A Dual-Track Drug Approval Process.

This process would release the relevant data behind the drug including its clinical trials on a web portal so that patients and their doctors can work out whether a new drug is suitable to them given their genetic markers. Madden and Smith explain the operation of the web portal for Free to Choose Medicine (FTCM) as follows:

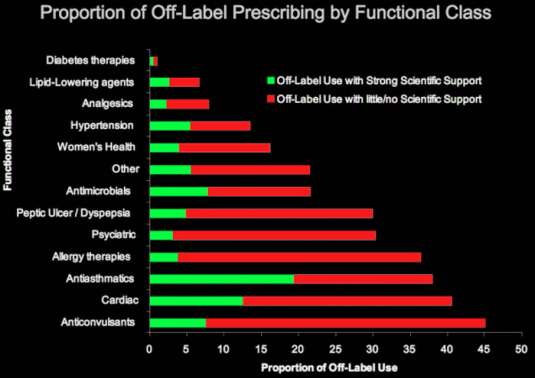

Doctors would be empowered to use their medical knowledge and in-depth knowledge of their patients similar to how they decide on off-label use for approved drugs, i.e., for uses that the FDA has neither tested nor approved but, in the opinion of doctors, are likely to be beneficial to patients. To gain early access, patients would purchase the drug from developers and consent to doctor and developer immunity from lawsuits except in the case of gross negligence or willful misconduct.

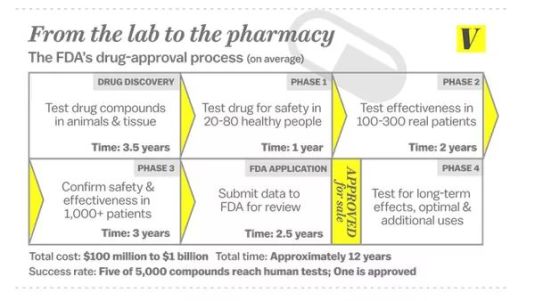

Off label use of medicines arises because the current Food and Drug Administration (FDA) process for drug approval has several phases. Phase 1 tests for the safety of the drug. Later phases are about whether the drug has its predicted effects. That should not be a concern of the FDA or its superfluous New Zealand equivalent Medsafe.

If a new drug isn’t better than the existing competition, that’s a problem for its investors for backing the wrong horse. It’s up to its investors and potential buyers to work out for themselves whether a new drug is more effective than the existing options. That’s a commercial decision, not a decision from regulators.

https://twitter.com/Carolynyjohnson/status/667696845615968257

Once a drug is approved by the FDA for particular uses, doctors and researchers often discover that a drug has other clinical applications.

Source: Pharma Marketing Blog

Rather than go through another round of FDA approvals, doctors simply prescribe that drug despite the fact it is not approved by the FDA for that particular clinical use. This is what is called off label prescription.

A number of US states have passed hopelessly unconstitutional Right to Try legislation that authorises the prescription of new drugs not approved by the FDA.

The Free to Choose Medicine proposal is similar to Right to Try legislation. Free to Choose Medicine would allow doctors to make their own prescription choices for their patients as long as the new drug has been shown to be safe. That is, it has passed Phase 1 of the FDA drug approval process. Phase 1 is about drug safety.

In 1962, an amended law gave the FDA authority to judge if a new drug produced the results for which it had been developed. Formerly, the FDA monitored only drug safety. It previously had only sixty days to decide this. Drug trials can now take up to 10 years.

https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser/status/627581135355310080

Sam Peltzman showed in a famous paper in 1973 that the 1962 amendments to US Federal drug approval laws reduced the introduction of effective new drugs in the USA from an average of forty-three annually in the decade before the 1962 amendments to sixteen annually in the ten years afterwards. No increase in drug safety was identified.

Peltzman found that the unregulated market quickly weeded out ineffective drugs prior to the 1962 law change in the USA. The sales of ineffective new drugs declined rapidly within a few months of their introduction.

Doctors stop prescribing medicines that don’t work. Patients complain quickly about medicines that don’t work. What matters is they had the chance to try this drug.

If economists have a bitter drinking song, a battle cry that unites the warring schools of economic thought all, it would be “how many people has the FDA killed today”. Many drugs became available years after they were on the market outside the USA because of drug approval lags at the FDA. The dead are many. To quote David Friedman:

In 1981… the FDA published a press release confessing to mass murder. That was not, of course, the way in which the release was worded; it was simply an announcement that the FDA had approved the use of timolol, a ß-blocker, to prevent recurrences of heart attacks. At the time timolol was approved, ß-blockers had been widely used outside the U.S. for over ten years. It was estimated that the use of timolol would save from seven thousand to ten thousand lives a year in the U.S. So the FDA, by forbidding the use of ß-blockers before 1981, was responsible for something close to a hundred thousand unnecessary deaths.

Free to Choose Medicine is an excellent way to break the regulatory deadlock over drug lags. Free to Choose Medicine should be adopted in New Zealand. Any new drug that has passed the phase 1 drug safety part of regulatory approval processes in any one of the USA, UK, Australia, Canada or Germany should be lawful to prescribe in New Zealand. New drugs should not have to go through the superfluous processes of Medsafe.

The existing drug regulatory regime is based upon making the drug safe for the average patient. That has been swept aside by pharmaceutical innovation as Madden and Smith explain:

Today’s world of accelerating medical advancements is ushering in an age of personalized medicine in which patients’ unique genetic makeup and biomarkers will increasingly lead to customized therapies in which samples are inherently small. This calls for a fast-learning, adaptable FTCM environment for generating new data.

In sharp contrast, the status quo FDA environment provides a yes/no approval decision based on statistical tests for an average patient, i.e., a one-size-fits-all drug approval process. In a FTCM environment, big data analytics would be used to analyze TEDD [Tradeoff Evaluation Drug Database] in general and, in particular, to discover subpopulations of patients who do extremely well or poorly from using a FTCM drug.

Recent Comments