https://twitter.com/KevinHague/status/673665100637560832

Green Party health spokesman Kevin Hague is right on the money when he says that Pharmac should not be politicised.

The promise of the opposition leader Andrew Little to fund an extremely expensive semi wonder drug from melanoma turned down for Pharmac funding was as unwise as it was well-meaning. The decision of the Labor Party to launch an online petition to fund the drug was unwise to the point of ghoulishness.

The leader of the opposition has promised to spend $200,000 per a drug that doesn’t work 66% of the time, but helps 34% of patients and cures 6% of patients. The average increase in life expectancy as a result of taking this new drug is about 18 months.

The limited last stage of cancer funding that was turned down was to cost $30 million: that is nearly 4% of Pharmac’s $800 million budget. Funding for the entire 2000 melanoma patients who might benefit from this new drug would cost more than half the entire Pharmac budget for a year – just one drug would cost this much!

Remember too that there are plenty more of these expensive semi-wonder drugs coming down the pipe.

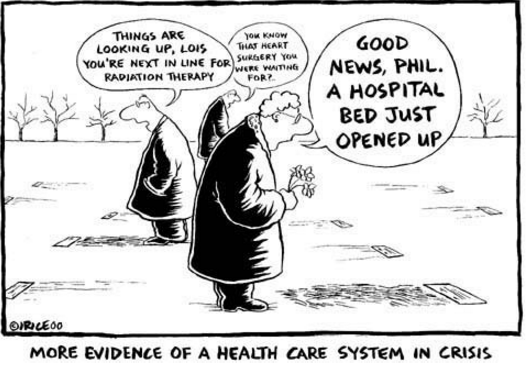

There is rationing in every area of government. There is always some poor bastard just over the other side of the line and all too often he has a sad story to tell.

In the health sector there always be someone who’s lifesaving drug was almost funded but was not, who was second on the organ donation waiting list or would have lived if the waiting list for surgery at the local public hospital was just that little bit shorter.

The proper response of ministers and parliament is to decide how much to allocate to each area, the rules whereby this funding is distributed and then appoint high-quality people to administer those rules. Fairness in this type of rationing is adherence to the rules laid down in advance by ministers and parliament.

Naturally, everyone be horrified if a politician was deciding who got the next kidney transplant. There are be outrage if a patient moved up the hospital waiting list because of political intervention.

It is the case of the seen and the unseen: it is obvious that someone misses out if there is politicisation of the kidney transplant waiting list or hospital waiting lists.

It is not so obvious that someone else’s drug is funded less generously or not at all if another drug with better publicists and lobbyist moves up the list for funding.

The reason why there is a separation of powers in medical rationing is to stop these injustices – to stop favouritism. Politicians fund the system and hire experts to administer it impartially.

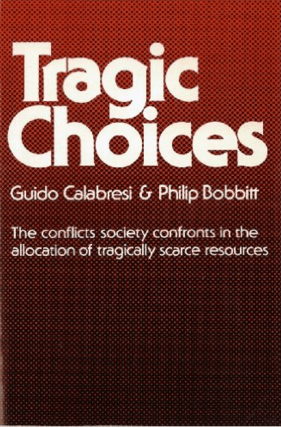

Gordon Tullock wrote a 1979 New York Law Review book about avoiding difficult choices. His review was of a book by Guido Calabresi and Philip Bobbitt called Tragic Choices. This book was about tragic choices involved in the allocation of kidney dialysis machines (a “good”), military service in wartime (a “bad”), and entitlements to have children (a mixed blessing).

Gordon Tullock wrote a 1979 New York Law Review book about avoiding difficult choices. His review was of a book by Guido Calabresi and Philip Bobbitt called Tragic Choices. This book was about tragic choices involved in the allocation of kidney dialysis machines (a “good”), military service in wartime (a “bad”), and entitlements to have children (a mixed blessing).

Tullock argued that we make a decision about rationing resources through the following steps:

- how much resources to allocate,

- how to distribute the allocated resources, and

- how to think about the previous two choices, which may have been very personally unpleasant to make because some had to miss out with tragic consequences for them.

To reduce the personal distress of making these tragic choices, Tullock observed that people often allocate and distribute resources in a different way so as to better conceal from themselves the unhappy choices they had to make. This includes funding drugs that have been refused by Pharmac if their supporters can mount a good publicity campaign.

Critically for our purposes here, Tullock argue that they do this even if this less personally distressing system of allocation and distribution means the recipients of these choices as a group are worse off and more lives are lost than if more open and honest choices about there are can only be so much that can be done to save lives. By less personally distressing, Tullock meant less personally distressing to the people making the decisions.

Campaigns to fund drugs remind the public of the specific individuals and groups who missed out on a potentially life-saving new drug. If the campaign presses the right buttons, the new drug is funded to make them go away and stop reminding politicians and the public of the tragic consequences of health budget rationing.

Hear no evil, see no evil. Politicians and the public are willing to pay to not be reminded of the tragic consequences of rationing in the health and pharmaceuticals budget.

Resources are reallocated and redistributed in a way that the political decision makers are less likely to find out that some patients missed out. Kevin Hague is absolutely right when he says

If $30Mn is spent every year on Keytruda, it won’t be available for other people with different conditions, on drugs for which it says it has better evidence of health gain. One of the missing parts of the debate is the voice of those whose lives will be saved, extended or otherwise improved because the medicines they need can be funded.

Hague with the chief executive of a district health board when there is a concerted public campaign to fund a breast cancer drug. Long courses of Herceptin had been turned down for Pharmac funding. The National Party campaigned in a subsequent election for the funding of this drug despite knowing the reservations of Pharmac about its cost effectiveness.

The trick is funding the drug sought by patients complaining about missing out by allocating less resources to many different current and future funding areas. These must be areas of funding where patients don’t know they are missing out or are waiting longer and perhaps living shorter lives as a result.

This concealment of the tragic choices involved in how the health system must allocate and distribute pharmaceutical funding is playing out before our very eyes this week.

Andrew Little by promising to fund and John Key by saying he might consider funding this particular semi-wonder drug does not increase the size of the Pharmac budget.

Unless the Pharmac budget is increased, someone else misses out on their lifesaving drug but we will never know who they are. Because they cannot complain because they do not know they have been disadvantaged by such political machinations, their political angst is not taken into account in the brutal political calculus of concealing of the tragic reality of medical rationing.

There is talk of an early access scheme. All that means is additional funding that could have gone to Pharmac’s next on its waiting list goes to politically sexier new drugs with less promise to save lives. If there is no additional funding, an early access scheme would institutionalise the politicisation of the tragic choices Pharmac must make every week.

Everybody is better off if ministers and the parliament face up to making tragic choices in drug funding and the rest of the health sector. Covering that up by funding whatever new drug gets in the media makes the issue go away for the next few news cycles but more patients die because they are moved down the waiting list for life-saving healthcare.

Dec 07, 2015 @ 18:20:00

“The promise of the opposition leader Andrew Little to fund an extremely expensive semi wonder drug from melanoma turned down for Pharmac funding was as unwise as it was well-meaning.”

You really believe it was well-meaning?

LikeLiked by 1 person