Many young women choose to not pursue science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) careers because there are other career options that allow them to better use their superior verbal and reading abilities.

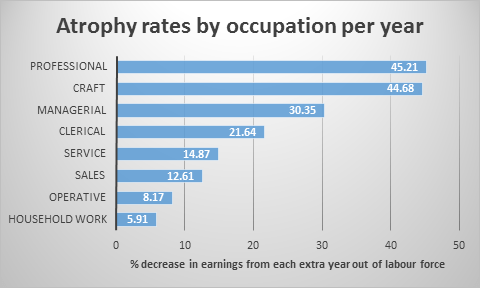

Further reasons for women to hesitate entering STEM occupations is their faster rate of human capital depreciation. It has been well known for a long time that human capital atrophy rates differ greatly by occupation and are much higher in professional, managerial and craft occupations.

Source: Polachek (1981).

Even a year out of the workforce can greatly reduce earning power because of a rapid depreciation of the human capital accumulated from certain occupations. Women make education and career choices that minimise these losses in light of periods away from work because of motherhood.

Women self-selecting to those occupations with low rates of human capital depreciation. As De Grip explains using German data:

…women who anticipate career interruptions for family reasons take account of the wage penalties related to such a break when they choose their occupational field, i.e. women select occupations where human capital deprecation during a career interruption is the lowest…

Our estimation results have important implications for public policies which attempt to encourage the interest of female students in technical studies and occupations. Obviously, the higher human-capital depreciation rates for workers with family-related career breaks in these male occupations can be a serious threshold for women to choose these occupations

Women choose the occupations that maximise the returns from their skills. Occupations that neither well-reward superior verbal and reading skills and have rapid rates of depreciation on occupational human capital are not a good investment for many of the women anticipating spells out of the workforce because of motherhood.

Rendall and Rendall (2015) recently investigated differential depreciation rates on verbal and maths skills in competing occupational choices for college educated women. Not surprisingly, they found that in the USA verbal skills suffered only minor depreciation during career interruptions but maths skills experience costly depreciation. They found that:

…college educated women avoid occupations requiring significant math skills due to the costly skill atrophy experienced during a career break. In contrast, verbal skills are very robust to career interruptions. The results support the broadly observed female preference for occupations primarily requiring verbal skills – even though these occupations exhibit lower average wages.

Thus, skill-specific atrophy during employment leave and the speed of skill repair upon returning to the labour market are shown to be important factors underpinning women’s occupational outcomes. This research suggests that a substantial portion of female occupational sorting could be determined by skill-specific atrophy-repair characteristics.

This is no surprise as verbal skills improve with age because of expanding vocabularies and better judgement based on accumulated experience. Maths skills tend to be the type of skills where your best years in your 20s and after that things fall away.

These findings by Rendall and Rendall reinforce the initial bias women have against STEM occupations because of their superior reading and verbal skills. STEM occupations are a poor career choice for women because they undervalue their innate skills and heavily penalise career interruptions.

Such is the fatal conceit of politicians is they want to encourage women to make poor education and occupational investments. Women self-selecting into vastly different occupations to men because they are smarter than the average politician about what is the best of them.

Differential atrophy rates on human capital as drivers of the gender wage gap and occupational segregation have nothing to do with the choices of employers – nothing to do with blameworthy behaviour on their part. The blameworthy behaviour can be explicit prejudice, implicit bias or statistical discrimination.

Much of occupational segregation is the result from self-selection by women into occupations on the basis of superior innate skills and the slow rates at which these verbal and reading skills depreciate with time both in general and with time away from the workforce.

Recent Comments