Unharnessed painters work amid the Eiffel Tower. Circa 1910. http://t.co/N7yE7OaKGm—

Old Pics Archive (@oldpicsarchive) June 13, 2015

Workplace safety arises as a by-product of economic growth. Risks in the workplace and outside that would not countenance now were routine a few decades ago because the risk of eliminating them was high.

The soon to take effect New Zealand health workplace safety legislation makes it much more difficult to have independent directors and part-time directors of companies. That will both weaken the ability of shareholders to prevent insider control as well as introduce a diversity of views onto boards of directors.

The resignation of Sir Peter Jackson is an example of this. Talented entrepreneurs are no longer able to run large numbers by sitting on the board and intervening on a management by exception basis.

Rupert Murdoch as an example of an executive able to run a global empire. He would ring up the chief executives of his subsidiaries for one minute to month. If they are talking about something interesting, he would listen for longer. He was the ultimate one-minute manager who built a global empire around his supreme entrepreneurial talent.

The new legislation on workplace safety will increase the cost of building a successful business from the ground up. Entrepreneurs will not be able to quickly intervene in the company and dismiss underperforming executives who look after things while they are away. This is because they are not on the Board of Directors.

One constraint on the growth of any firm is entrepreneurs have a limited span of control (Coase 1937; Williamson 1967, Lucas 1978; Oi 1983a, 1983b). A span of control is the number of subordinates that an individual supervisor has to control and lead either directly or through a hierarchical managerial chain (Fox 2009). There are only so many tasks that even the most able of entrepreneurs can carry out in one day. Over-stretched spans of control motivate entrepreneurs to hire professional managers and delegate to them a wide range of decision-making rights over the firms they own (Williamson 1975; Foss, Foss and Klein 2008).

Entrepreneurs and the professional managers they hired to assist them must divide their respective time between monitoring employees, identifying new business opportunities, forecasting buyer demand and running the other aspects of their business (Lucas, 1978; Oi 1983, 1983b, 1988; Foss, Foss, and Klein 2008). The larger is the firm, the more employees there are for the entrepreneur to direct, monitor and reward. These costs of directing and monitoring employees will increase with the size of the firm and larger firms will encounter information problems not present in smaller firms (Alchian and Demsetz 1972; Stigler 1962)

The time of the more talented entrepreneurs is more valuable because they had the superior managerial skills and entrepreneurial alertness to make their firms large in the first place and remain deft enough to survive in competition. Time spent on the supervision of employees is time that is spent away from other uses of the talents that got these more able entrepreneurs to the top and keeps them there (Williamson 1967; Lucas 1978; Oi 1983b, 1988, 1990; Idson and Oi 1999; Black et al 1999).

Firms in the same industry tend to exhibit systematic differences in their organization of production and the structure of their workforces because entrepreneurial ability is the specific and scarce production input that limits the size of a firm (Lucas, 1978; Oi 1983b). The less able entrepreneurs tend to run the smaller firms while the better entrepreneurs tend to lead both the currently large firms and the smaller firms that are growing at the expense of market rivals (Lucas 1978, Oi 1983b; Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950).

There has been a tremendous improvement in the working conditions over the 20th century. The main driver was the incentive and employers to provide safe workplaces as real wages grew. Adam Smith noted that more dangerous and unpleasant jobs always attracted a wage premium as he explains in the Wealth of Nations:

The five following are the principal circumstances which, so far as I have been able to observe, make up for a small pecuniary gain in some employments, and counterbalance a great one in others: first, the agreeableness or disagreeableness of the employments themselves; secondly, the easiness and cheapness, or the difficulty and expense of learning them; thirdly, the constancy or inconstancy of employment in them; fourthly, the small or great trust which must be reposed in those who exercise them; and, fifthly, the probability or improbability of success in them.

First, the wages of labour vary with the ease or hardship, the cleanliness or dirtiness, the honourableness or dishonourableness of the employment. Thus in most places, take the year round, a journeyman tailor earns less than a journeyman weaver. His work is much easier. A journeyman weaver earns less than a journeyman smith. His work is not always easier, but it is much cleanlier. A journeyman blacksmith, though an artificer, seldom earns so much in twelve hours as a collier, who is only a labourer, does in eight. His work is not quite so dirty, is less dangerous, and is carried on in daylight, and above ground.

Honour makes a great part of the reward of all honourable professions. In point of pecuniary gain, all things considered, they are generally under-recompensed, as I shall endeavour to show by and by. Disgrace has the contrary effect.

The trade of a butcher is a brutal and an odious business; but it is in most places more profitable than the greater part of common trades. The most detestable of all employments, that of public executioner, is, in proportion to the quantity of work done, better paid than any common trade whatever.

Hunting and fishing, the most important employments of mankind in the rude state of society, become in its advanced state their most agreeable amusements, and they pursue for pleasure what they once followed from necessity. In the advanced state of society, therefore, they are all very poor people who follow as a trade what other people pursue as a pastime. Fishermen have been so since the time of Theocritus. A poacher is everywhere a very poor man in Great Britain. In countries where the rigour of the law suffers no poachers, the licensed hunter is not in a much better condition. The natural taste for those employments makes more people follow them than can live comfortably by them, and the produce of their labour, in proportion to its quantity, comes always too cheap to market to afford anything but the most scanty subsistence to the labourers.

Disagreeableness and disgrace affect the profits of stock in the same manner as the wages of labour. The keeper of an inn or tavern, who is never master of his own house, and who is exposed to the brutality of every drunkard, exercises neither a very agreeable nor a very creditable business. But there is scarce any common trade in which a small stock yields so great a profit…

The wages in any particular job will vary with the risks that are known to the worker in that job. That is an important qualification.

Competition in labour markets ensures that the net advantages of different jobs will tend to equality. This theory of the labour market originating in Adam Smith, which drives much of modern labour economics became to be known as the theory of compensating differentials.

Firms can choose their production technology to offer workers greater safety or they can economize on safety and offer the savings to workers in the form of higher wages. There is a trade-off in offering more safety or higher wages, holding constant the level of profits. As Kip Viscusi explains:

Wage premiums paid to U.S. workers for risking injury are huge—in 1990 they amounted to about $120 billion annually, which was over 2 percent of the gross national product, and over 5 percent of total wages paid.

These wage premiums give firms an incentive to invest in job safety because an employer who makes his workplace safer can reduce the wages he pays. Employers have a second incentive because they must pay higher premiums for workers’ compensation if accident rates are high.

One of the effects of safety regulation is the employers no longer have to pay this wage premium in more dangerous or disagreeable jobs but as Fishback wrote:

Studies of wages before and after the introduction of workers’ compensation show, however, that non-union workers’ wages were reduced by the introduction of workers’ compensation. In essence, the non-union workers “bought” these improvements in their benefit levels.

Even though workers may have paid for their benefits, they still seem to have been better off as a result of the introduction of workers’ compensation. Many workers had faced problems in purchasing accident insurance at the turn of the century. Workers’ compensation left them better insured, and allowed many of them to spend some of their savings that they had set aside in case of an accident.

What literature there is about suggest that workers overestimate small risks and underestimate large risks. Surveys of manufacturing employment show that one third of workers quit because they found out the job they accepted was more dangerous than they expected.

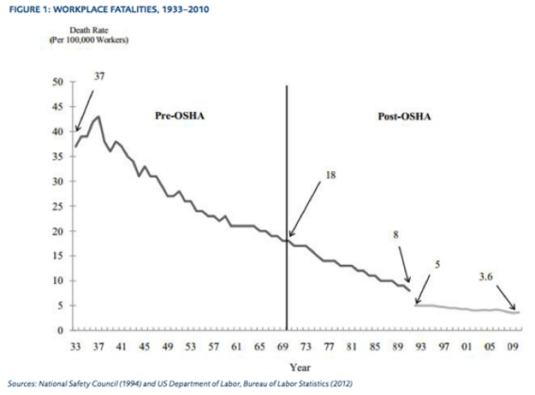

Source: Evaluating OSHA’s Effectiveness and Suggestions for Reform | Mercatus

One clear trend of the 20th century is as countries got richer, workers demanded more safety at work and larger wage premiums. Market incentives for better worker safety dwarf legal incentives such as from being sued, which in turn dwarf regulatory incentives.

There is also evidence of a glass coffin effect. About 95% of workplace deaths of men. Indeed, there are some interesting journal papers about how occupational choice is affected by motherhood, sole motherhood and sole fatherhood. Single parents are more cautious about their occupational choices.

It is unfortunate that the unions in New Zealand opposes a risk based system of workers’ compensation. The current system is not only no fault, employers pay premiums based on the risks of their industry, not of their individual workplace. There is plenty of evidence to show the charging premiums based on the risks of an accident and the previous record of workplace safety greatly reduces workplace deaths and injuries as Viscusi explains:

The workers’ compensation system that has been in place in the United States throughout most of this century also gives companies strong incentives to make workplaces safe. Premiums for workers’ compensation, which employers pay, exceed $50 billion annually. Particularly for large firms, these premiums are strongly linked to their injury performance.

Statistical studies indicate that in the absence of the workers’ compensation system, workplace death rates would rise by 27 percent. This estimate assumes, however, that workers’ compensation would not be replaced by tort liability or higher market wage premiums.

Recent Comments