Elsby, Shin and Solon (2016) have published a paper throwing a spanner in the works for business cycle theories premised on downward wage rigidity:

We devote particular attention to the hypothesis that downward nominal wage rigidity plays an important role in cyclical employment and unemployment fluctuations. We conclude that downward wage rigidity may be less binding and have lesser allocative consequences than is often supposed.

Keynesian macroeconomics is premised on downward wage rigidity. There is mass unemployment during recessions because employers are unwilling or unable to cut wages.

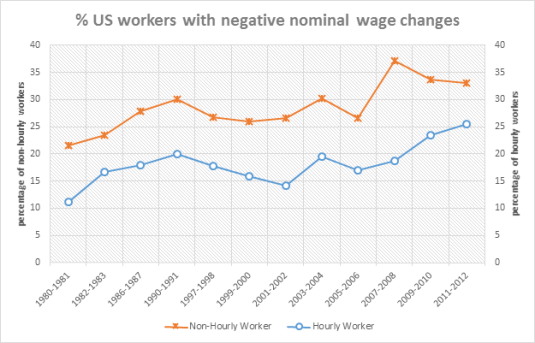

Elsby, Shin and Solon (2016) found that a non-trivial fraction of workers report nominal wage reductions: at least 10% of hourly workers and 20% of non-hourly workers. This fraction of workers whose nominal wage has been cut has been increasing since 1980 as shown in the chart below. The remaining workers either experienced a nominal wage freeze or a nominal wage increase in that year.

“What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle?” by Richard Blundell, Claire Crawford and Wenchao Jin found that in the recent British recession, 12% of employees in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage freezes and 21% of workers in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage cuts.

These results from the USA and UK come as no surprise to me because I have been on a collective employment agreement where after a restructuring, my pay was cut. The alternative was to leave and not receive a redundancy payment.

Chris Pissarides(2009), The Unemployment Volatility Puzzle: Is Wage Stickiness the Answer?, Econometrica argued the wage stickiness is not the answer to explaining unemployment since wages in new job matches are highly flexible:

1. wages of job changers are always substantially more procyclical than the wages of job stayers.

2. the wages of job stayers, and even of those who remain in the same job with the same employer are still mildly procyclical.

3. there is more procyclicality in the wages of stayers in Europe than in the United States.

4. The procyclicality of job stayers’ wages is sometimes due to bonuses, and overtime pay but it still reflects a rise in the hourly cost of labor

to the firm in cyclical peaks

I have been on several individual and collective agreements that grandfathered pay and conditions for existing workers and paid recruits less. I have lost count of the number of retirement pension scheme closed to new employees since I first encountered this cost saving practice at my first lecture at University.

My commercial law lecturer was explaining that he was lecturing part-time. His main job dealing with the litigation that might arise out of closing of the University retirement pension scheme. Some top-class academics had to retire earlier than they planned because of this closure to avoid a reduction in their pensions.

Most of my friends in the private sector are on bonus schemes were the great majority of the bonus is based on company profitability. Indeed, I know one company where everyone from the CEO down loses their bonus if there is a fatal workplace accident.

How can downward wage rigidity be a scientific hypothesis if the extensive international evidence of widespread nominal wage cuts wage cuts since the 1980s and 40%+ of the workforce on performance bonuses is not enough to refute it?

The same edition of the Journal of Labour Economics had a paper by Edward Lazear about how workplace effort varies with the business cycle and employment conditions:

…it seems that employers push their employees harder during recessions as they cut back the work force and ask each of the remaining workers to cover the tasks previously performed by the now-laid-off workers.

A number of models of long-term contracting in the labour market suggest that the level of employee effort expected varies with peak loads and general labour market conditions. That is understood from the start and is not is regarded as some form of opportunism by the employer after the contract is signed.

Likewise, employers do not lay off workers as soon as they become unprofitable in a downturn. If they did so, they would write off valuable firm specific human capital that might become profitable soon once the market recovers.

It is much easier to explain mass unemployment during a recessionas a a burst of layoffs at the beginning of the recession followed by the time it takes the unemployed to find suitable new vacancies and for employers to find it profitable to create such vacancies.

Some of these unemployed will simply wait for conditions to improve their existing industrial occupation so as to preserve their specialised human capital. These unemployed can be characterised as waiting unemployment or rest unemployment.

Other jobseekers will search further afield in new industries and occupations. These unemployed either have human capital that more general and mobile across many industries or have decided to scrap their industry specific and occupation specific human capital and try something else. The downturn in their current industry or occupation may be of sufficient duration that they regard waiting is a poor investment.

The economic concept of unemployment was rather primitive until Hutt write his hard to read theory of idle resources in 1939, Stigler’s paper in 1962 and the Phelps book in 1970.

I found Lucas and Prescott’s islands model to be an excellent explanation of unemployment. Lucas and Prescott’s economy is composed of a large number of scattered islands. Each of these islands is a one local labour market.

Workers in each of these islands have no precise knowledge of what wages will prevail in the economy outside of their own local labour market. Workers either remain on their island or leave it for what they expect to be a more alluring job further afield. Some workers are unemployed crossing between the islands, but they are nevertheless engaging in optimizing behaviour because they are looking for a better job than they have now.

Alchian (1969) lists three ways to adjust to unanticipated demand fluctuations:

• output adjustments;

• wage and price adjustments; and

• Inventories and queues (including reservations).

Alchian (1969) suggests that there is no reason for wage and price changes to be used regardless of the relative cost of these other options:

• The cost of output adjustment stems from the fact that marginal costs rise with output;

• The cost of price adjustment arises because uncertain prices and wages induce costly search by buyers and sellers seeking the best offer; and

• The third method of adjustment has holding and queuing costs.

There is a tendency for unpredicted price and wage changes to induce costly additional search. Long-term contracts including implicit contracts arise to share risks and curb opportunism over sunken investments in relationship-specific capital. These factors lead to queues, unemployment, spare capacity, layoffs, shortages, inventories and non-price rationing in conjunction with wage stability.

1 Comment (+add yours?)