The Greens co-leader James Shaw has today called for New Zealand to re-introduce deposit insurance saying that

“It would be a small levy placed on the banks, which would go into an insurance fund. It’s been operating successfully in many, many other countries.” But Mr Shaw said the Government and Reserve Bank keep putting off the change, saying customers can choose the bank they believe is most stable. “Consumers are not well educated about the stability of banks, so what that means is they tend to flow to the really big Australian-owned banks.”

Deposit insurance has a long history of promoting banking instability and irresponsible lending. It has not operated successfully in other countries nor in New Zealand. The Green Party announcement made no mention of New Zealand’s recent experience with deposit insurance

At the height of the global financial crisis and in the final days of the 2008 general election, New Zealand not only extended a deposit guarantee to its banks it also did so to finance companies. As the Auditor-General recorded in her recent report

On Sunday 12 October 2008, at the peak of the global financial crisis, the Government decided that it needed to implement a form of retail deposit guarantee scheme to avoid a flight of funds from New Zealand institutions to those in Australia. It needed to do this urgently: The Crown Retail Deposit Guarantee Scheme (the Scheme) was designed and announced that same day.

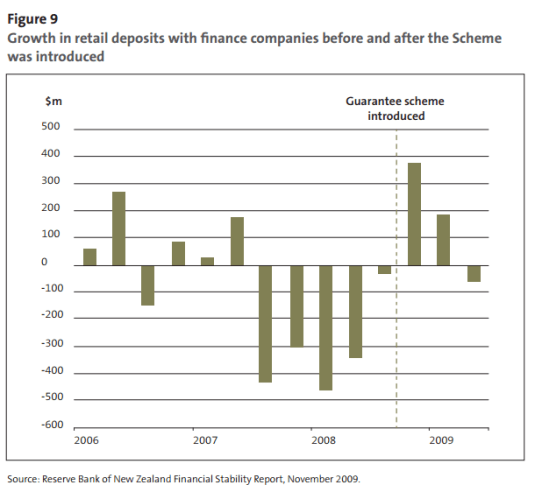

The deposit guarantee was extended to finance companies. Money flooded into previously high risk investments as investors had nothing to lose and everything to gain from the higher returns.

As the Auditor-General noted in a 2015 recent report reviewing the scheme

From the outset, the advice from officials recognised that the decision to include finance companies in the Scheme carried significant risk. Once deposits with these companies were guaranteed, depositors could safely move investments to where they would get the highest return, irrespective of the risk of company failure.

The finance companies also had less reason to minimise risk in their investment activity. The Crown was carrying much of this risk. During 2009, the Treasury watched some of that behaviour eventuate. Deposits with finance companies under the Scheme grew, in some instances significantly. We saw one example where a finance company’s deposits grew from $800,000 to $8.3 million after its deposits were guaranteed. At South Canterbury Finance Limited, the deposits grew by 25% after the guarantee was put in place.

The flood of deposits into finance company after the deposit guarantee somewhat undermines the low opinion the Greens have of depositors as investors sensitive to risk

On blunting incentives, otherwise known as ‘moral hazard’, Bill English can’t seriously expect everyday savers to analyse the loan books of banks to assess their credit risk when they open their accounts, let alone do this on a six-monthly basis.

At its height, the bank and finance company guarantees totalled over $133 billion. Ninety-six institutions were covered by the scheme – 60 non-bank deposit takers, 12 banks and 24 collective investment schemes. All guarantees had ended by December 2011.

To put context on the risk that the taxpayer, this $133 billion underwritten by the taxpayer return for little or no insurance fee was nearly twice the amount the Government spends in a year, or about 2/3rd of GDP.

If a financial institution in the Scheme failed, taxpayers would repay all of the money that eligible people had deposited or invested, up to a cap of $1 million each.

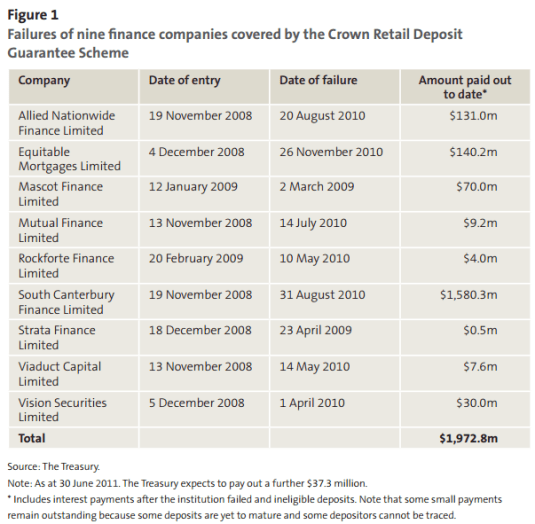

Nine finance companies out of the 30 accepted into the scheme failed. This resulted in payments by the taxpayer to the investors of $2 billion. Expected recoveries are currently estimated at about $0.9 billion after the completion of the various receiverships of these institutions according to the recent report on the scheme by the Auditor-General.

The deposit guarantee was extended to the finance companies despite 28 such companies failing between 2006 and 2008. This included some larger finance companies such as Bridgecorp Finance (New Zealand) Limited, Provincial Finance Limited, and Hanover Finance Limited.

FDR was initially opposed to deposit insurance in the USA in 1933 because it would encourage greater risk taking by banks. Sam Peltzman in the mid-1960s found that U.S. banks in the 1930s halved their capital ratios after the introduction of federal deposit insurance.

If you want to make banks safer, increase their capital ratios and require them to have more subordinated debt in their capital requirements.

Any form of deposit insurance requires extensive regulation of insured bank portfolios to prevent excessive risk-taking. The Kareken and Wallace model of deposit insurance which is based on moral hazard, predicts that if a government sets up deposit insurance and doesn’t regulate bank portfolios to prevent them from taking too much risk, the government is setting the stage for a financial crisis. The Kareken-Wallace model makes you very cautious about lender-of-last-resort facilities and very sensitive to the risk-taking activities of banks.

Kareken and Wallace called for much higher capital reserves for banks and more regulation to avoid future crises. It is much easier to require banks to put up more capital than to not take risks with the monies invested in them by depositors.

Recent Comments