Adam Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments

13 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in Alfred Marshall, history of economic thought

Did Gary Becker invent the term human capital?

11 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in Alfred Marshall, Gary Becker, history of economic thought, human capital, labour economics

..

The marvel of the market: the remarkable foresight of young adults in choosing what to study

16 Jan 2015 1 Comment

in Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, economics of education, George Stigler, human capital, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice, politics - New Zealand, rentseeking Tags: 2nd laws of supply and demand, Alfred Marshall, Armen Alchian, george stigler, search and matching, skills shortgaes

Known but yet to be exploited opportunities for profit do not last long in competitive markets, including hitherto unnoticed opportunities for the greater utilisation and development of skills and experience (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; and Kirzner 1992). Moneyball is the classic example of entrepreneurial alertness to hitherto unexploited job skills which were quickly adopted by competing firms (Hakes and Sauer 2006, 2007).

There is considerable evidence that the demand and supply of human capital responds to wage changes. For example, over- or under-supplied human capital moves either in or out in response to changes in wages until the returns from education and training even out with time (Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Ehrenberg 2004).

As evidence of this equalisation of returns on human capital investments across labour markets, the returns to post-school investments in human capital are similar – 9 to 10 percent – across alternative occupations, and in occupations requiring low and high levels of training, low and high aptitude and for workers with more and less education (Freeman and Hirsch 2001, 2008). There is evidence that workers with similar skills in similarly attractive jobs, occupation and locations earn similar pay (Hirsch 2008; Vermeulen and Ommeren 2009; Rupert and Wasmer 2012; Roback 1982, 1988).

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found that the labour supply and university enrolment decisions of engineers is “remarkably sensitive” to career earnings prospects. Graduates are the main source of new engineers. Engineers who moved out into other occupations such as management did not often moved back to work again as professional engineers. Ryoo and Rosen (2004) observed when summarising their work that:

Both the wage elasticity of demand for engineers and the elasticity of supply of engineering students to economic prospects are large. The concordance of entry into engineering schools with relative lifetime earnings in the profession is astonishing.

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) found several periods of surplus in the market for engineers. These periods of shortage or surplus corresponded to unexpected demand shocks in the market for engineers such as the end of the Cold War.

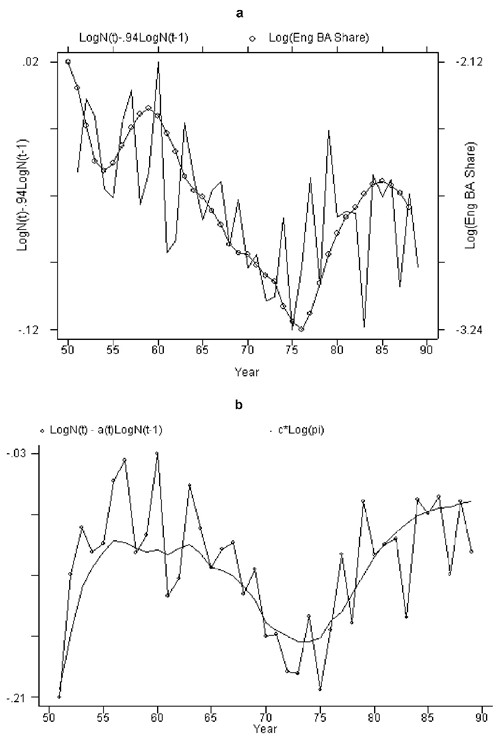

Figure 1: New entry flow of engineers: a, actual vs. imputed from changes in stock of engineers; b, time-varying coefficients.

Source: Ryoo and Rosen (2004)

Ryoo and Rosen (2004) noted that importance of permanent versus transitory changes in earnings. Transitory rises and falls in earnings prospects have much less influence on occupational choices and the educational investments of students.

In light of these findings that the supply of engineers rapidly adapted to changing market conditions, Ryoo and Rosen (2004) questioned whether public policy makers have better information on future labour market conditions than labour market participants do. When politicians get worked up about skill shortages, the markets for scientists and engineers often where they make extravagant claims about the ability of the market to adapt to changing conditions because of the long training pipeline involved in university study, including at the graduate level.

There can be unexpected shifts in the supply or demand for particular skills, training or qualifications. These imbalances even themselves out once people have time to learn, update their expectations and adapt to the new market conditions (Rosen 1992; Ryoo and Rosen 2004; Bettinger 2010; Zafar 2011; Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang 2012; Webbink and Hartog 2004).

For example, Arcidiacono, Hotz and Kang (2012) found that both expected earnings and students’ abilities in the different majors are important determinants of student’s choice of a college major, and 7.5% of students would switch majors if they made no forecast errors.

The wage premium for a tertiary degree was low and stable in New Zealand in the 1990s (Hylsop and Maré 2009) and 2000s (OECD 2013). This stability in the returns to education suggests that supply has tended to kept up with the demand for skills at least over the longer term at the national level. There were no spikes and crafts that would be the evidence of a lack of foresight among teenagers in choosing what to study.

All in all, the remarkable sensitivity of engineers to a career earnings prospects, the frequent changes of college majors by university students in response to changing economic opportunities, and the stability of the returns on human capital over time suggest that the market for human capital is well functioning.

The argument that the market was not working well was assumed rather than proven. Likewise, the case for additional subsidies for science, technology, engineering and mathematics because of perceived skill shortages has not been made out. There is a large literature showing that the market for professional education works well.

The onus is on those who advocate intervention to come up with hard evidence, rather than innate pessimism about markets that are poorly understood because of a lack of attempts to understand it. Studies dating back to the 1950s by George Stigler and by Armen Alchian found that the market for scientists and engineers works well and the evidence of shortages were more presumed than real.

The power and self-discipline of parsimonious analysis

30 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in Alfred Marshall, David Friedman, economics, George Stigler, Karl Popper Tags: methodology of economics

Some bristle over the small size of the basic analytical tool kit of economists and the leanness of the behavioural assumptions therein (Stigler 1987).

Simpler explanations and more parsimonious abstractions are better ‘engines for the discovery of concrete truth’ about how people will respond to changes in their economic and social environments.

A limited set of causes or postulates in a theory reduces the chances that one or more of the assumptions on a more extensive list inadvertently explains away in an ad hoc manner every possible anomaly, or allows for a deft reinterpretation and/or adaptation to temporise and escape refutation. An every growing number of auxiliary hypotheses and ah hoc assumptions to co-op inconvenient facts may forever immunise the basic theory under scrutiny against testing and falsification (Olson 1982; Popper 1963). More parsimonious abstractions are less likely to found theories that seem to have successfully explained a particular social phenomenon spuriously by chance.

Complex human objectives are not assumed in economic analysis because everything could be explained and nothing could be falsified. Every empirical anomaly could be covered in advance by assuming human objectives that are sufficiently complex and large enough in number that are pursued with a high frequency of error and inertia (Friedman 1990; Popper 1963).

Subsequent ad hoc reinterpretations that add new objectives or additional sources of human frailty can finesse major anomalies to make the basic theory compatible with the facts to side-step refutation. Heavily qualified theories and intricate explanations of narrow application rarely come in the open for long enough to be found wanting.

A good theory is a prohibition: the theory forbids certain things to happen. The more that a theory forbids, the better the theory is. Bold, novel and chancy predictions are even better still.

These predictions are less likely to explain social and economic behaviour spuriously by chance. If incorrect or incomplete, bold and novel predictions are more likely to be quickly found at odds with experience and the basic theory is either revised or is discarded (Popper 1963).

The Social Possibilities of Economic Chivalry (1907)

10 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in Alfred Marshall, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation Tags: moral hazard, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

A Government could print a good edition of Shakespeare’s works, but it could not get them written…

I am not urging that municipalities should avoid all such undertakings without exception. For, indeed, when a large use of rights of way, especially in public streets, is necessary, it is doubtless generally best to retain the ownership, if not also the management, of the inevitable monopoly in public hands.

I am only urging that every new extension of Governmental work in branches of production which need ceaseless creation and initiative is to be regarded as prima facie anti-social, because it retards the growth of that knowledge and those ideas which are incomparably the most important form of collective wealth.

The Right Minimum Wage: $0.00 – New York Times 1987–Updated Again

19 May 2014 1 Comment

in Alfred Marshall, applied welfare economics, David Friedman, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: David Card, interpersonal comparision of utility, Milton Friedman, minimum wage, offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, The pretense to knowledge

Raising the minimum wage by a substantial amount would price working poor people out of the job market.

A far better way to help them would be to subsidize their wages or – better yet – help them acquire the skills needed to earn more on their own…

Raise the legal minimum price of labour above the productivity of the least skilled workers and fewer will be hired.

If a higher minimum means fewer jobs, why does it remain on the agenda of some liberals?

A higher minimum would undoubtedly raise the living standard of the majority of low-wage workers who could keep their jobs. That gain, it is argued, would justify the sacrifice of the minority who became unemployable.

The argument isn’t convincing. Those at greatest risk from a higher minimum would be young, poor workers, who already face formidable barriers to getting and keeping jobs. Indeed, President Reagan has proposed a lower minimum wage just to improve their chances of finding work.

What does the New York Times say in 2014?

The minimum wage is specifically intended to take aim at the inherent imbalance in power between employers and low-wage workers that can push wages down to poverty levels.…

The weight of the evidence shows that increases in the minimum wage have lifted pay without hurting employment

Both the White House and the New York Times are not the best of Bayesian updaters because the author of the one study on which they are very much hang their hats for their policy conclusions about no job losses from a minimum wage increase interprets his results with very much less zeal than they do:

I think careful research on the topic has found that for this range of minimum wage increase, the almost unmistakable conclusion is that there will be little in the way of job losses, while the wages of low-end workers will get a boost (his underlining).

The claims of the White House and the New York Times that the minimum wage can be lifted without hurting employment are a long bow from what Andrajit Dube said about small changes in the minimum wage having small adverse effects on unemployment:

What Andrajit Dube said s not much different from everyone else on the minimum wage – Nuemark is an example:

a 10 per cent increase in the minimum wage could reduce young adult employment by up to 2 per cent

David Card was always very careful amount about how his pioneering research was about how small increases in the minimum wage not reducing employment in the presence of search and matching costs:

From the perspective of a search paradigm, these policies make sense, but they also mean that each employer has a tiny bit of monopoly power over his or her workforce.

As a result, if you raise the minimum wage a little—not a huge amount, but a little—you won’t necessarily cause a big employment reduction. In some cases you could get an employment increase.

There is always offsetting behaviour: Barry Hirsch found that when the federal minimum wage went up in 2007, businesses just made their employees work harder to justify the expense.

I am always surprised that people might think that the minimum wage will have anywhere near its intended effects after market participants have had time to act to counter its effects as Peltzman explains:

Regulation creates incentives for behaviour to offset some or even all of the intended effect of the regulation…

Regulation seldom changes the forces that produces the particular results the regulators seek to change. So we need to ask whether the regulation really changes result or only the form in which the market forces assert themselves.

Is a minimum wage increase a Pareto improvement – a policy action done in an economy that harms no one and helps at least one person?

Obviously there are winners and losers from a minimum wage increase and these wins and loses must be summed up in some way as they are for all public policy changes.

When there are winners and losers from deregulation, the only thing seems to matter to many of those who support a minimum wage increase are the losses to the incumbent industry and its often well-paid workers rather than the gains to consumers, rich or poor.

For there to be a Marshall improvement, the sum of all of the gains and losses must sum to a positive.

A Marshall improvement from a minimum wage or any other change is measured by adding utilities as if everyone receives the same utility from a dollar. A dollar is a dollar to everyone as David Friedman explains:

A net improvement in the sense used by Marshall–what I have elsewhere called a Marshall improvement–is a change whose net value is positive, meaning that the total value to those who benefit, measured as the sum of the number of dollars they would each, if necessary, pay to get the change, is larger than the total cost to those who lose, measured similarly.

The advantage of the Marshall improvement criterion is we commonly observe people’s values of different things by seeing how much they are willing to pay for it.

Alfred Marshall was aware that treating people as if they all had the same utility for a dollar was a stretch but this was considered less relevant for policy changes that affect large and diverse groups of people. Individual differences could be expected to cancel out over a broad suite of policies in a well-functioning democracy so that most people gain in net terms through time. David Friedman explains:

I prefer to use the Marshallian approach, which makes the interpersonal comparison explicit, instead of hiding it in the ‘could be made but isn’t’ compensating payment…

a change that benefits a millionaire by $10 and costs a pauper $9 is a potential Pareto improvement, since if combined with a payment of $9.50 from the millionaire to the pauper it would benefit both. If the payment is not made, however, the change is not an actual Pareto improvement.

The ‘potential Paretian’ approach reaches the same conclusion as the Marshallian approach and has the same faults; it simply hides them better. That is why I prefer Marshall…

It is worth noting that although a Marshall improvement is usually not a Pareto improvement, the adoption of a general policy of ‘Wherever possible, make Marshall improvements’ may come very close to being a Pareto improvement…

Add up all the effects and, unless one individual or group is consistently on the losing side, everyone, or almost everyone, is likely to benefit.

This is the latest review of the minimum wage research from David Neumark:

The potential benefits of higher minimum wages come from the higher wages for affected workers, some of whom are in poor or low-income families.

The potential downside is that a higher minimum wage may discourage employers from using the low-wage, low-skill workers that minimum wages are intended to help.

If minimum wages reduce employment of low-skill workers, then minimum wages are not a “free lunch” with which to help poor and low-income families, but instead pose a trade-off of benefits for some versus costs for others.

Research findings are not unanimous, but evidence from many countries suggests that minimum wages reduce the jobs available to low-skill workers.

George Stigler set-out the conditions for a minimum wage to achieve its purported objectives in 1946, which have not been bettered:

If an employer has a significant degree of control over the wage rate he pays for a given quality of labour, a skilfully-set minimum wage may increase his employment and wage rate and, because the wage is brought closer to the value of the marginal product, at the same time increase aggregate output…

This arithmetic is quite valid but it is not very relevant to the question of a national minimum wage. The minimum wage which achieves these desirable ends has several requisites:

1. It must be chosen correctly… the optimum minimum wage can be set only if the demand and supply schedules are known over a considerable range…

2. The optimum wage varies with occupation (and, within an occupation, with the quality of worker).

3. The optimum wage varies among firms (and plants).

4. The optimum wage varies, often rapidly, through time.

A uniform national minimum wage, infrequently changed, is wholly unsuited to these diversities of conditions.

The case for a minimum wage was therefore hung, drawn and quartered in 1946 by Stigler. Not every cause and effect is open to policy manipulation because of the lack of the necessary knowledge about the relationship and insufficiently deft policy tools to exploit that knowledge in a timely fashion and as circumstances change. This information and organisational burden is such that the process of setting minimum wage increases is an example of public policy making that is groping about in the dark. Success can be neither appraised in advance nor later retrospectively determined.

Recent Comments