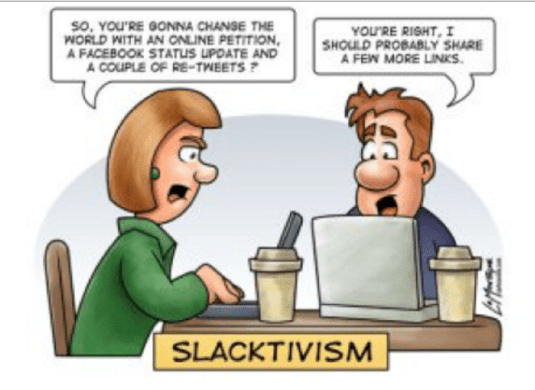

The rise of Jeremy Corbyn has reminded me of how lazy political activists happen to be. For all their lifelong agitating, they think that as soon as they get a degree of prominent, their work is done. Suddenly, everyone who has disagreed with accidentally prominent activists for all that life will flock to their side and they will win the next election.

The thing about being a political fringe dwelling is you are a political fringe dweller. Only a tiny percentage of the population support you. To get anything above that requires hard work and a considerable amount of compromise to expand your base.

Those that already agree with you already agree with you. If you want more to agree with you, you have to start agreeing with those that disagree with you rather than they agree with you. It is a slow laborious process of compromise.

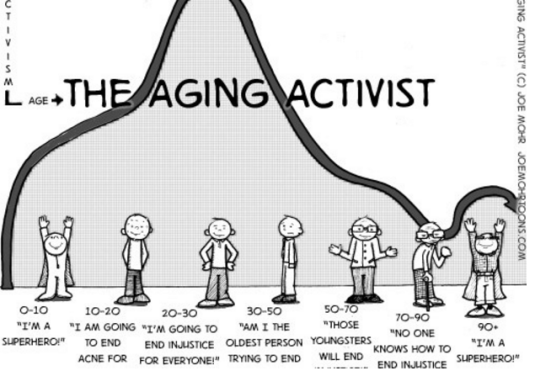

Occasionally, parties rush to prominence. Left-wing and right-wing populists are examples of these as are the anti-immigration parties. Their support is soft and can quickly disappear. Trump, Corbyn and Sanders should remember this.

Most of all, political activists who slip into prominence forget that voters tend to vote retrospectively: on past performance and out of anger than voting for a particular agenda of the alternative parties.

Because of this political ignorance and apathy, Richard Posner championed Schumpeter’s view of democracy. Schumpeter disputed the widely held view that democracy was a process by which the electorate identified the common good, and that politicians carried this out:

- The people’s ignorance and superficiality meant that they were manipulated by politicians who set the agenda.

- Although periodic votes legitimise governments and keep them accountable, their policy programmes are very much seen as their own and not that of the people, and the participatory role for individuals is limited.

Schumpeter’s theory of democratic participation is that voters have the ability to replace political leaders through periodic elections. Citizens do have sufficient knowledge and sophistication to vote out leaders who are performing poorly or contrary to their wishes.

The power of the electorate to turn elected officials out of office at the next election gives elected officials an incentive to adopt policies that do not outrage public opinion and administer the policies with some minimum honesty and competence.

That lack of competence and judgement are what will bring Trump, Corbyn and Sanders down. They are just not up to the job. There are better left-wing and right-wing populists and firebrands about.

The outcome of Schumpeterian democracy in the 20th century, where governments are voted out rather than voted in, is most of modern public spending is income transfers that grew to the levels they are because of support from the average voter.

Political parties on the Left and Right that delivered efficient increments and stream-linings in the size and shape of government were elected, and then thrown out from time to time, in turn, because they became tired and flabby or just plain out of touch.

There is considerable excitement about how popular and elite preferences seem to have equal chances are being implemented.

If Americans at different income levels agree on a policy, they are equally likely to get what they want. But what about the other half of the time? What happens when preferences across income levels diverge?

When preferences diverge, the views of the affluent make a big difference, while support among the middle class and the poor has almost no relationship to policy outcomes. Policies favored by 20 percent of affluent Americans, for example, have about a one-in-five chance of being adopted, while policies favored by 80 percent of affluent Americans are adopted about half the time. In contrast, the support or opposition of the poor or the middle class has no impact on a policy’s prospects of being adopted.

These patterns play out across numerous policy issues. American trade policy, for example, has become far less protectionist since the 1970s, in line with the positions of the affluent but in opposition to those of the poor. Similarly, income taxes have become less progressive over the past decades and corporate regulations have been loosened in a wide range of industries.

This is a dewy eyed view of democracy that would make HL Mencken proud. The notion of a democracy is governed by the rule of law, checks and balances and the protection of minority rights is lost in these dewy eyed conception is a democracy. As Matthew Yglesias said:

…the idea that the point of democracy is to implement legislative outcomes that are supported by broad-based surveys seems almost like a straw man dreamed up by an eighteenth-century monarchist.

Gilens concedes that other values—the protection of minority rights, for example—may also be important, but this misses the forest for the trees. The purpose of a political system is to resolve political questions in a satisfactory way….

The watchword of democracy should not be responsiveness but rather accountability.

In a well-functioning system, voters should elect a team of politicians and then fire them if their performance is seen as unsatisfactory. Seen in this light, the problem with American democracy today is that the intersection of counter-majoritarian legislative procedures and increased partisan polarization has blurred the lines of responsibility.

My confidence in the median voter theorem returned when Bryan Caplan and Sam Peltzman pointed out that it is difficult to point to a major government program in the 20th century that does not have majority support.

Director’s law is the bulk of public programmes are designed primarily to benefit the middle classes but are financed by taxes paid primarily by the upper and lower classes. Based on the size of its population and its aggregate wealth, the middle class will always be the dominant interest group in a modern democracy.

Within this framework of accountability and voting on the basis of performance rather than promise, there is considerable rotation of power. The fact that this particular activist or populists stumbled onto the treasury benches does not mean much. They usually got there because the previous administration was no longer seen as competent. Nothing more than that.

Recent Comments