Hard rock: the challenge of the Awatere Valley Road slip

19 Dec 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters, transport economics Tags: earthquakes

Earthquakes + Engineering – Normal People Edition

25 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters

M7.8 Kaikoura Earthquake computer simulation

23 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters

Kaikoura Earthquake: Papatea Fault Drone flyover

22 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters

Kaikoura earthquake and aftershocks – 8 days on

22 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters

The varying risk of tsunamis around the world

19 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

Map showing the varying risk of tsunamis around the world tsunami-alarm-system.com/fileadmin/medi… http://t.co/hFMIU7MucN—

Beautiful Maps (@BeautifulMaps) September 10, 2015

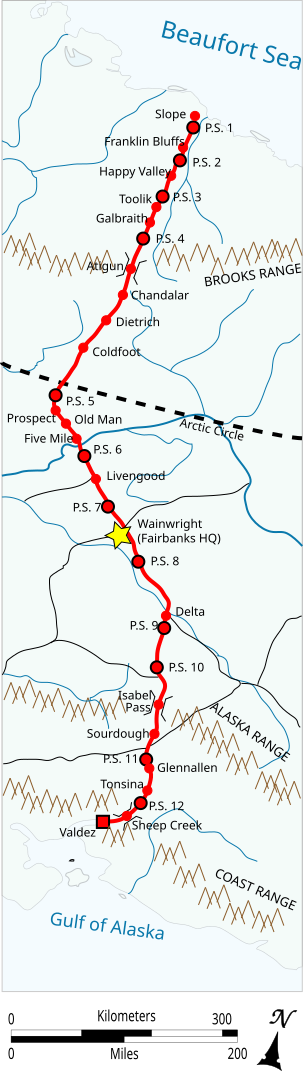

#nzeq Post-disaster labour market adjustment: Alaska in the pipeline era & Darwin after Cyclone Tracy

17 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters, labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, transport economics, urban economics Tags: Alaska, Cyclone Tracy

Experiences from abroad suggest that labour markets have a history of rapid adaptation to regional surges in construction demand and that workers are prepared to tolerate lower quality housing provided there are compensating wage premiums.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline was the largest privately funded construction project to that time. Alaskan wages during the building period between 1974 and 1977 were very flexible in the construction and related industries.

Labour supply was responsive in terms of more hours worked per worker and more local workers entering the workforce with many others moved temporarily to Alaska even though the Alaskan climate and culture would not appeal to everyone.

The Alaskan labour force increased by 50%, from about 50,000 to about 90,000 workers, hours worked per week increased by about the same, and many people worked 2 jobs.

High school hours were moved to the morning so that students and their teachers could take an afternoon job in pipeline construction. There is hot beading of accommodation and a 1000% labour turnover rate at the local McDonald’s. By 1979, the Alaskan labour force returned pretty much to its preconstruction era size.

Moving to a region still prone to after-shocks also would not appeal to everyone. Many energy industry construction projects in modern times were completed in unappealing locations and extreme climates on land and sea.

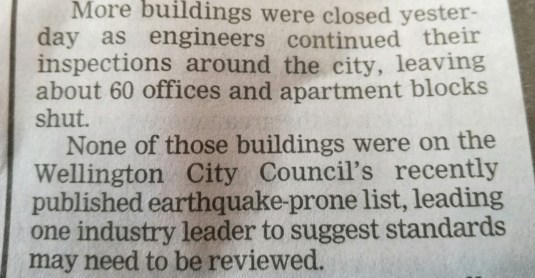

As another and much nearer example, Cyclone Tracy destroyed about 60 per cent of the 8,000 houses in Darwin on 24 December 1974 and more than 30 per cent were severely damaged. Most of Darwin’s population of 48,000 people became homeless; 71 lives were lost.

After a mass evacuation of 35,000, Darwin’s population was 10,000 by 1 January 1975. Darwin’s population recovered to 30,000 by May 1975. This influx was dominated by newcomers, especially construction workers. Temporary housing, caravans, hotels and an ocean liner were all pushed into service.

When the Darwin Reconstruction Commission was wound up two years ahead of the initial reconstruction timeline on 12 April 1978, 3,000 new dwellings had been completed. By mid-1978, the city could again house its pre-Tracy population numbers. Darwin is now home for about 125,000 people.

The key role of housing costs in disaster recovery @ericcrampton @JordNZ #nzeq

16 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, economics of natural disasters, economics of regulation, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, urban economics Tags: land supply, land use planning, NYMBYs, RMA, zoning

The evidence abroad after earthquakes, hurricanes, flooding, tornados, and wartime bombing is that for growing cities, disasters, including carpet bombing and atomic bombs, are only temporary set-backs with few long-run economic and population consequences. A few years after a disaster, these cities even recover the industries they had before their calamities.

For growing cites, the loss of housing and other destruction does not affect the underlying demand from workers and businesses to be at the location. Florida has prospered despite over twenty hurricanes striking since 1988 and five of the six most damaging Atlantic hurricanes of all time striking since 1988.

Cities that are already in decline drop down onto an even faster downward population and economic trend after a major natural disaster. A large scale destruction of housing takes away the one compensating feature of these declining cities, which was cheap housing.

Housing prices in declining cities are usually well below construction costs. Low living costs partly offset the relative lack of local economic opportunity in these cities. New Orleans is an example of a declining city that did not recover fully from a disaster for this reason.

After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans had much higher costs of housing because of flood damage but there were limited local economic opportunities to attract back old and new residents. About 20 per cent of the Katrina evacuees did not return.

Natural disasters be they earthquakes or hurricanes turn declining cities and towns from a dump with cheap housing to a dump with expensive housing. They can be a killer blow.

The main policy enabler of growing cities in the USA has been the avoidance of land use regulations that raise housing costs. Over the past 20 years, the fastest growing U.S. regions have not been those with the highest income or most attractive climates.

Flexible housing supply is the key determinant of regional growth. Land use regulations drive housing supply and determine which regions are growing. A regional approach to enabling increases in land and housing supply might reduce the tendency of many localities to block new construction.

Post-disaster co-operation: The voluntary provision of weakest-shot public goods

16 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of natural disasters, public economics Tags: economics of alliances, free riding, post-disaster cooperation, public goods, weakest shot public goods

After a natural disaster, both the economic and social fabric and the survival of individual employers each become weakest-shot public goods. The provision of these public goods temporarily depend by much more than is usual on the minimum individual contributions made – the weakest shots made for the common good. The supply of most public goods usually is not dependent on the contributions of any one user.

The classic example of a weakest shot public good by that brilliant applied price theorist Jack Hirschleifer is a dyke or a levee wall around a town. It is only as good as the laziest person contributing to its maintenance on their part of the levee. Vicary (1990, p. 376) lists other examples:

Similar examples would be the protection of a military front, taking a convoy across the ocean going at the speed of the slowest ship, or maintaining an attractive village/landscape (one eyesore spoils the view).

Many instances of teamwork involve weak-link elements, for example moving a pile of bricks by hand along a chain or providing a theatrical or orchestral performance (one bad individual effort spoils the whole effect.)

Most doing the duty is essential to the survival of all after a natural disaster. The alliances we call societies and the firm, normally not in danger of collapse, are threatened if there is a natural disaster. In these highly unusual circumstances, alliance-supportive activities, greater cooperativeness and self-sacrifice become an important public good.

In normal periods when threats are small, what social control mechanisms that are in place are sufficient and there is no need for exceptional behaviour and self-sacrifice.

Everyone has an interest in the continuity of the economic and social fabric and the survival of their employers in times of adversity. Individual contributions to these national and local public goods become much more decisive after a natural disaster.

In normal times people behave in a conventionally cooperative way because individually they find it profitable to do so. There is some slippage around the edges and there are social control mechanisms to deter illegal conduct and supply public goods.

As the threat to the social and economic fabric grows after a natural disaster, eventually the social and economic balance may hang by a hair. When this is so, any single person can reason that his own behaviour might be the social alliance’s weakest link. International military and political alliances also rise and fall on this weakest link basis.

How to get back to the eastern suburbs from the CBD after an earthquake #eqnz

16 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters, politics - New Zealand, transport economics, urban economics Tags: earthquakes

Take the bus. But not a trolley bus. We were going to walk home (7.8 km) but once we got to the edge of Mount Victoria, bus drivers were picking people up.

Buses could not get into the centre of town because of gridlock, so drivers showed the initiative to go to the perimeter of the CBD and going back out and in on their normal routes. They picked up many people. Do not start me on how useless trolley buses are after a natural disaster

Recent Comments