.@SenSanders: Open borders? That’s a Koch brothers proposal

20 Jul 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, development economics, economics of education, international economic law, international economics, International law, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA, Public Choice, unemployment Tags: anti-foreign bias, economics of immigration

Would a proposal to quickly double the New Zealand minimum wage ever be entertained?

15 Jul 2018 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: expressive politics

J.D. Vance on Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of Family and Culture in Crisis – Full interview

06 Jun 2018 Leave a comment

in economic history, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: success sequence

Everybody Hates Chris S03E08 – Everybody Hates #MinimumWage

09 Apr 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage, television Tags: offsetting behaviour, The fatal conceit, unintended consequences

Favourite deleted #livingwage tweet

06 Apr 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, minimum wage, politics - USA, poverty and inequality

.

Corporate Profits Explained (Bernie Sanders CEO of Walmart??)

17 Jan 2018 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage

#FightFor15 must have been an ambit claim?

24 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA

https://twitter.com/EconBizFin/status/626687442834300928

The fight for $15 movement in the minimum wage could not have been serious about doubling the minimum wage to $15.

Perhaps to their own surprise, they won despite living in what they say is an oligarchic political system dominated by the rich which keeps the poor poorer and poorer.

Why California’s #minimumwage will backfire, Part I: CA is business-hostile now@Mark_J_Perry goo.gl/7wbr14 https://t.co/y1pF4UGATK—

AEIdeas Blog (@AEIdeas) April 05, 2016

California, New York, San Francisco and Seattle are among the states and cities increasing their local minimum wages, currently of up to $12, to $15 by 2021 or 2022.

There is nothing special about minimum wages when it comes to mandating wage rises. If it is safe to double the minimum wage, it is safe to double everybody’s wage. That logic is undeniable.

The efficiency wage and inequality of bargaining power arguments that suggest that the wage rise will be paid out of employers’ profits are not special to minimum wage employers.

https://twitter.com/dylanmatt/status/720786520509165568

If minimum wage employers can handle a doubling of their labour costs, any employer can handle the doubling of the cost of employing any of their employees?

Some such as Arindrajit Dube say that these very large wage increases by cities and states in their federal system are experiments “worth running and monitoring” (Lane 2016). As Dube said recently:

“… 30 to 40 percent of the California workforce will get a raise … This will be a big experiment. It’s far outside of our evidence base… If you’re risk-averse, this would not be the scale at which to try things. On the other hand, if you think that wages are really low and they’ve been low for a really long time and we can afford to take some risks, doing things at this scale will get us more evidence” (Lee 2016).

Noah Smith (2016) concluded that the empirical literature on minimum wages suggests that a 10% minimum wage increase would reduce employment by about 2% so doubling the federal minimum wage would see the employment of young people go down by one-fifth. Smith (2016) said this is a

“small but real effect — a $15 federal minimum wage might throw a million kids out of work”.

You should remember that in the USA, if you lose your job, your unemployment insurance is time-limited.

Venn Diagram of the Day on the $15 Minimum Wage…… https://t.co/aANb26iShi—

Mark J. Perry (@Mark_J_Perry) November 29, 2015

It is not like New Zealand where you can stay on the unemployment benefit forever if you are priced out of the market by a doubling of the minimum wage.

Since I was indirectly quoted in a WaPo op-ed on CA min wage, here's exactly what I wrote to Mr. Lane. (@tylercowen) https://t.co/Q326lgyvzz—

Arindrajit Dube (@arindube) March 31, 2016

What happens to minimum wage workers who lost their jobs because of the large minimum wage increase after their unemployment insurance runs out?

Bryan Caplan on why the minimum wage increase must kill jobs

22 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

1. The literature on the effect of low-skilled immigration on native wages. A strong consensus finds that large increases in low-skilled immigration have little effect on low-skilled native wages. David Card himself is a major contributor here, most famously for his study of the Mariel boatlift. These results imply a highly elastic demand curve for low-skilled labor, which in turn implies a large disemployment effect of the minimum wage.

This consensus among immigration researchers is so strong that George Borjas titled his dissenting paper “The Labor Demand Curve Is Downward Sloping.” If this were a paper on the minimum wage, readers would assume Borjas was arguing that the labor demand curve is downward-sloping rather than vertical. Since he’s writing about immigration, however, he’s actually claiming the labor demand curve is downward-sloping rather than horizontal!

2. The literature on the effect of European labor market regulation. Most economists who study European labor markets admit that strict labor market regulations are an important cause of high long-term unemployment. When I ask random European economists, they tell me, “The economics is clear; the problem is politics,” meaning that European governments are afraid to embrace the deregulation they know they need to restore full employment. To be fair, high minimum wages are only one facet of European labor market regulation. But if you find that one kind of regulation that raises labor costs reduces employment, the reasonable inference to draw is that any regulation that raises labor costs has similar effects – including, of course, the minimum wage.

3. The literature on the effects of price controls in general. There are vast empirical literatures studying the effects of price controls of housing (rent control), agriculture (price supports), energy (oil and gas price controls), banking (Regulation Q) etc. Each of these literatures bolsters the textbook story about the effect of price controls – and therefore ipso facto bolsters the textbook story about the effect of price controls in the labor market.

If you object, “Evidence on rent control is only relevant for housing markets, not labor markets,” I’ll retort, “In that case, evidence on the minimum wage in New Jersey and Pennsylvania in the 1990s is only relevant for those two states during that decade.” My point: If you can’t generalize empirical results from one market to another, you can’t generalize empirical results from one state to another, or one era to another. And if that’s what you think, empirical work is a waste of time.

4. The literature on Keynesian macroeconomics. If you’re even mildly Keynesian, you know that downward nominal wage rigidity occasionally leads to lots of involuntary unemployment. If, like most Keynesians, you think that your view is backed by overwhelming empirical evidence, I have a challenge for you: Explain why market-driven downward nominal wage rigidity leads to unemployment without implying that a government-imposed minimum wage leads to unemployment. The challenge is tough because the whole point of the minimum wage is to intensify what Keynesians correctly see as the fundamental cause of unemployment: The failure of nominal wages to fall until the market clears.

From http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2013/03/the_vice_of_sel.html

But is a living wage policy still worth a try?

24 Oct 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA

https://twitter.com/EconBizFin/status/626687442834300928

Demands for massive pay rises for the low-paid are not just confined to New Zealand. The US debate is worth reviewing because their living wage advocates are so upfront about the job losses.

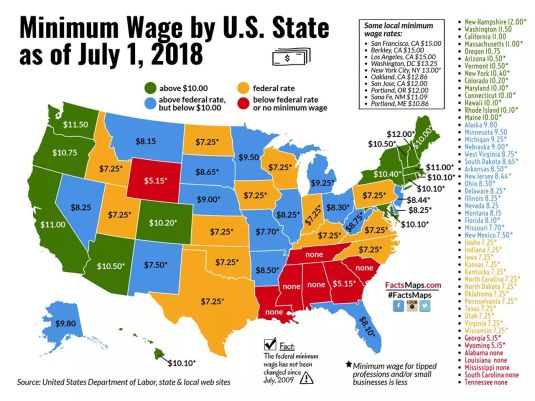

US living wage activists such as Fight for $15 want to double their federal minimum wage from $7.25 per hour to $15 per hour. California, New York, San Francisco and Seattle are among the states and cities increasing their local minimum wages, currently of up to $12, to $15 by 2021 or 2022.

Some such as Arindrajit Dube say that these very large wage increases by cities and states in their federal system are experiments “worth running and monitoring” (Lane 2016). As Dube said recently:

“… 30 to 40 percent of the California workforce will get a raise … This will be a big experiment. It’s far outside of our evidence base…

If you’re risk-averse, this would not be the scale at which to try things. On the other hand, if you think that wages are really low and they’ve been low for a really long time and we can afford to take some risks, doing things at this scale will get us more evidence” (Lee 2016).

Noah Smith (2016) concluded that the empirical literature on minimum wages suggests that a 10% minimum wage increase would reduce employment by about 2% so doubling the federal minimum wage would see the employment of young people go down by one-fifth. Smith (2016) said this is a “small but real effect — a $15 federal minimum wage might throw a million kids out of work”.

Should activists use minimum wage breadwinners for policy experiments? Noah Smith (2016) considers balancing the one million unemployed teenagers against the wage gains for adults as “necessary for a decision”.

Smith suggests that the large minimum wage increases in some US states and cities will tell us how big this welfare trade-off between jobs and wage rises is:

We don’t really know what happens when you raise the minimum wage to $15 — but soon, we will know. We will be able to see whether employment rates fall in L.A., Seattle, and San Francisco. We will be able to see whether people who can’t get work migrate from these cities to cities with lower minimum wages.

We will be able to see if employment growth suddenly slows after the enactment of the policy. In other words, federalism will do its job, by allowing cities to act as policy laboratories for the rest of the country (Smith 2015).

“Big experiments” involving large minimum wage increases to “provide clear evidence” to quote Dube’s words (Scheiber and Lovett 2016) are wrongheaded as Robert Lucas has explained:

I want to understand the connection between in the money supply and economic depressions. One way to demonstrate that I understand this connection–I think the only really convincing way–would be for me to engineer a depression in the United States by manipulating the U.S. money supply.

I think I know how to do this, though I’m not absolutely sure, but a real virtue of the democratic system is that we do not look kindly on people who want to use our lives as a laboratory. So I will try to make my depression somewhere else (Lucas 1988).

Leading reasons for economic theory, empirical research and the study of economic history are to warn the present against repeating past errors and not try experiments that are folly (Rosen 1993). There is too much group think and not enough courage of your vocation (see Dylan Matthew’s tweet below).

https://twitter.com/dylanmatt/status/720786520509165568

Australian-born economist Justin Wolfers is frank about the wishful thinking in the US debate:

But if you are interested in what level to set the minimum wage, the existing literature is nearly hopeless. Plausible reforms lie far outside the bounds of historical experience.

We don’t have useful estimates of the extent to which employment effects vary with the minimum wage. Since policymakers tend to implement short-run fixes, we know a lot about the effects of temporary reforms, but very little about the consequences of lasting reform (Wolfers 2016).

Most of the empirical studies are of the jobs lost over the next few years. When estimates have a 10 to 15-year horizon with time enough for entry, exit and technological adaptation and automation, a “long-run disemployment effect that is five times larger than the short-run effect” is in evidence (Aaronson, French, Sorkin 2016; Aaronson, French, Sorkin and To forthcoming; Sorkin 2015).

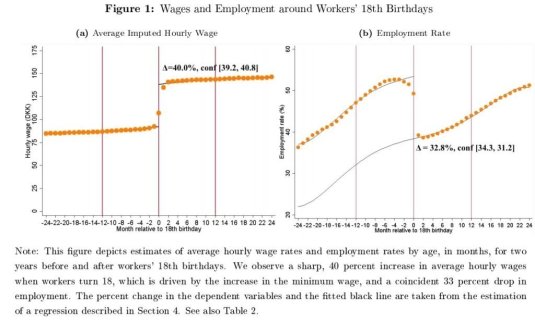

Danish minimum wage goes up by 40% at age 18

30 Sep 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: expressive voting, offsetting behaviour

Source: http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/449066/minimum-wage-study-denmark-finds-big-hit-employment

What Does Research Tell Us About Minimum Wage?

16 Sep 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: unintended consequences

Recent Comments