The leads and lags on monetary policy are long and variable

25 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, monetarism, monetary economics Tags: leads and lags on monetary policy, Milton Friedman, monetary policy

Many Keynesians, Friedman notes, advocate “leaning against the wind.” By this they mean, in some sense, that the monetary (and fiscal) authorities should try to balance out the private sector’s excesses rather than passively hope that it adjusts on its own.

There are large uncertainties about the size and timing of responses to changes in monetary policy. There is a close and regular relationship between the quantity of money and nominal income and prices over the years. However, the same relation is much looser from month to month, quarter to quarter and even year to year.

Monetary policy changes take time to affect the economy and this time delay is itself highly variable. The lags on monetary policy are three in all:

- The lag between the need for action and the recognition of this need (the recognition lag)

-

The lag between recognition and the taking of action (the legislation lag)

-

the lag between action and its effects (the implementation lag)

These delays mean that is it difficult to ascertain whether the effects of monetary policy changes in the recent past have finished taking effect. Secondly, it is difficult to ascertain when proposed changes in monetary policy will take effect. Thirdly, feedbacks must be assessed. The magnitude of the monetary adjustment necessary to deal with the problem at hand is thus never obvious. It is common for a central bank to act incrementally. The central bank makes small adjustments to monetary conditions over time as more information is available on the state of the economy and forecasts are updated.

The existence of lags may mean that by the time policy has its full effect, the problem with which it was meant to deal may have disappeared.

Milton Friedman (1959) tested the Fed’s success at leaning “against the wind” by checking whether the rate of money growth has truly been lower during expansions and higher during contractions. He admits that this method of grading he Fed’s performance is open to criticism, but he decided to go ahead and see what turns up. Friedman found that Fed has – for the periods surveyed – been unsuccessful.

By this criterion, for eight peacetime reference cycles from March 1919 to April 1958. Actual policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 155 months, in the ‘wrong’ direction in 226 months; so actual policy was ‘better’ than the [constant 4% rate of money growth] rule in 41% of the months.

Nor is the objection that the inter-war period biased his study is good since Friedman found that:

For the period after World War II alone, the results were only slightly more favourable to actual policy according to this criterion: policy was in the ‘right’ direction in 71 months, in the ‘wrong’ direct in 79 months, so actual policy was better than the rule in 47% of the months.

One of the best ways to parry a metaphor is with another metaphor. Keynesians have a host of metaphors in their rhetorical arsenal; one frequently voiced is that a wise government should “lean against the wind” when choosing policy. Friedman counters:

We seldom know which way the economic wind is blowing until several months after the event, yet to be effective, we need to know which way the wind is going to be blowing when the measures we take now will be effective, itself a variable date that may be a half year or a year or two from now. Leaning today against next year’s wind is hardly an easy task in the present state of meteorology.

Friedman’s remarks, as even his strong critics admit, are mighty and strike at the heart of any activist stabilisation policy. By meeting Keynesians on their own theoretical turf and scrutinising their practice, Friedman manages to produce objections that both Keynesians and non-Keynesians must take seriously. A key part of any response to Friedman rests on the ability of forecasters to do their jobs with tolerable accuracy.

Keynesian policies do not necessarily follow even if the Keynesian theory of the business cycle were conclusively proved. It must also be demonstrated that the government has the ability and willingness of the government to act as the theory prescribes. Friedman’s critique does not depend on the quantity theory of money.

The mirage of cost-push inflation

17 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in inflation targeting, macroeconomics Tags: Bill Allen, cost-push inflation, lags on monetary policy

It does appear too many that rising costs push up prices, but this impression is an illusion caused by the way inventories delay the effect of money supply increases on retail prices.

When increased money growth causes total spending to rise more quickly, sales of particular businesses will increase. But sales fluctuate from day to day and week to week, so managers of these businesses cannot immediately know that this sales increase will last.

As sales continue to rise, restaurants will use up their inventories. Larger orders will then be placed with suppliers, and inventories of these suppliers will begin to shrink.

The retail price has not yet changed because inventories have absorbed the initial impact of the increased spending.

But as more orders to replace depleted inventories work their way down the chain of distribution, orders for too wholesalers also will rise faster.

The available inventories are inadequate to meet the rising amounts demanded at existing prices.

As a result, wholesale prices will rise as packers bid more intensely for scarce factory supplies. These higher prices then cause factories and other base suppliers to raise their prices; and higher wholesale prices cause retailers to charge more.

As higher prices work their way up the distribution chain to the consumer, they create an illusion that higher costs are pushing up prices.

But both costs and prices are being pulled up by the increased spending caused by a more rapidly growing money stock. Because the effects of more money and more spending are delayed by inventories, hasty conclusions about the cause of inflation can be deceptive.

HT: Bill Allen

The Reserve Bank Governor (2013) versus the Labour Party on whether its monetary policy upgrade will increase the inflation rate and destabilise the exchange rate

07 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in inflation targeting, macroeconomics, politics - New Zealand Tags: exchange rate intervention, exchange rate targeting, inflation targeting

Attempts to keep the dollar from going “too high” would have ruinous domestic consequences as the Governor of the Reserve Bank explained last year:

If New Zealand decided to cap the NZ dollar, depending on where the cap is enforced, similar levels of intervention might be required as global foreign exchange turnover in NZ dollars relative to GDP is similar to that in Swiss francs.

The OCR would need to drop to zero first in order to eliminate the interest arbitrage motivation for NZ dollar inflows. Any attempt to retain non-zero interest rates by “sterilising” such massive intervention would be very difficult.

In effect therefore a Swiss type operation to cap the value of the NZ dollar through large scale FX intervention would also amount to quantitative easing. As I mentioned, this would be highly inflationary in the NZ context.

Graeme Wheeler, Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand

20 February 2013

Sterilised interventions in the foreign exchange market are a fool’s errand

If exchange rate manipulation had any chance of working, the U.S. Fed, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan would be all over it already. Their mutual efforts to depreciate their own currencies would cancel out.

Most central banks gave up on exchange rate interventions in the mid-1990s because attempts to manipulate exchange rates without loosening monetary policy rarely worked. Brute experience taught them that they were on fool’s errand.

These exchange rate interventions, known as sterilised interventions, become an independent source of exchange rate instability and invite counter-speculation by currency traders and hedge funds. Every hint that a central bank might intervene in the exchange rate invites currency speculation. As Milton Friedman said:

The central problem is not designing a highly sensitive [monetary] instrument that offsets instability introduced by other factors [in the economy], but preventing monetary arrangements becoming a primary source of instability…

By trying to move the value of the dollar, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand will add its own element of currency instability and invite counter speculation by currency traders and hedge funds. This is a dangerous game for a small Reserve Bank to play.

As stated by Paul Krugman in 1999 on the concept of the impossible trinity: free capital movement, a fixed exchange rate, and an effective monetary policy –

The point is that you can’t have it all: A country must pick two out of three.

It can fix its exchange rate without emasculating its central bank, but only by maintaining controls on capital flows (like China today); it can leave capital movement free but retain monetary autonomy, but only by letting the exchange rate fluctuate (like Britain – or Canada); or it can choose to leave capital free and stabilize the currency, but only by abandoning any ability to adjust interest rates to fight inflation or recession (like Argentina today or for that matter most of Europe).

Exchange rate manipulation by the Reserve Bank cannot alter the competiveness of exporters. The looser monetary policy will inevitably lead to higher CPI inflation that will erode any temporary advantage to exporters from the initial depreciation of the NZ dollar.

What did the Swiss do to keep their exchange rate down in the GFC?

Labour’s Monetary Policy Upgrade referred to the efforts of the Swiss National Bank to cap a massive appreciation of the Swiss Franc after 2009 and the Euroland sovereign debt crisis:

The Swiss have actively protected their currency from appreciating to the detriment of their tradeable sector (p.16)

The Swiss National Bank stemmed the rise of Swiss franc by loosening their monetary policy as they say so themselves:

The Swiss National Bank stemmed the rise of Swiss franc by loosening their monetary policy as they say so themselves:

The Swiss National Bank has successfully maintained its exchange-rate floor against the euro, often through heavy nonsterilized purchases of foreign exchange (Swiss National Bank Annual Report, 2012, p. 34).

These non-sterilised exchange rate interventions were a loosening of Swiss monetary policy. The Swiss National Bank happens to be one of a number of central banks that conduct their monetary policies by buying and selling in the foreign exchange markets.

Labour’s aim of a positive external balance through a tightening of monetary policy is a repeat of the fool-hardy policies of the Hawke-Keating government in the late 1980s.

1988 witnessed a major monetary policy tightening in Australia. The tightening was motivated by a current account deficit rather than double-digit inflation:

- The inflation rate fell to below 3% in 1991.

- The current account did not change much as a result of the deep recession and 10%+ unemployment rate designed to bring it under control.

The current account deficit as a major policy problem was then quietly forgotten in Australia.

Three conflicting monetary policy objectives

The New Zealand Labour Party wants the Reserve Bank to do three impossible things before breakfast:

- Loosen monetary policy to bring the dollar down such as in Switzerland after 2009;

- Tighten monetary policy to reduce the current account deficit such as in Australia after 1988; and

- Loosen and tighten monetary policy as required to stay within the inflation target.

The best contribution of monetary policy to the competitive positions of exporters is low inflation.

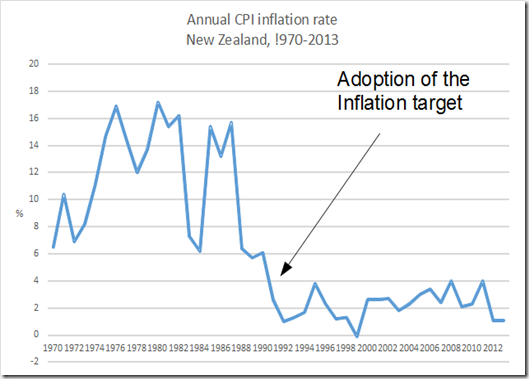

Inflation targeting removes monetary policy as in independent source of exchange rate instability. Attempts to manipulate the exchange rate undermines the inflation target that has been such a great success since 1989, and reduces the commitment of public policy to a stable, predictable business climate. Bordo and Humpage add:

…sterilised foreign-exchange intervention can sometimes affect exchange-rate movements, but sterilised intervention does not provide central banks with a mechanism for systematically altering exchange rates independent of their monetary policies.

Attempts to stabilise or undervalue exchange rates necessarily weaken a country’s control of its monetary policy and ultimately leave the real exchange rate unaffected.

What really matters?

Labour’s monetary policy upgrade is a distraction from the only game in town for the future prosperity of New Zealanders:

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.

Paul Krugman

The Age of Diminishing Expectations (1994)

2014 Homer Jones Memorial Lecture – Robert E. Lucas Jr.

18 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

The first part of his lecture discusses how the Fed can influence inflation and financial stability.

Central banks can control inflation. Can central banks maintain economic stability’s financial stability? This is still an open question as to whether central banks can do that. The quantity theory of money makes certain sharp predictions about monetary neutrality which are well borne out by the cross country evidence.

In the second part of this lecture, Lucas discusses how central banks around the world have used inflation targeting to keep inflation under control.

What is the Fed to do with the stable relationship between money and prices? Inflation targeting is superior to a fixed growth monetary supply growth rule. This always pushes policy in the direction of the inflation rate you want. Central banks around the world have succeeded in keeping inflation low by explicitly or implicitly targeting the inflation rate.

In the last part of his lecture, Lucas discusses financial crises. he agrees with Gary Gordon’s analysis that 2008 financial crisis was a run on Repo. A run on liquid assets accepted as money because they can be so quickly changed into money. The effective money supply shrank drastically when there was a run on these liquid assets.

Lucas favoured the Diamond and Dybvig of bank runs as panics. The logic of that model applies to the Repo markets now was well as to the banking system. How to extend Glass–Steagall Act type regulation of bank portfolios to the Repo market is a question for future research.

Inflation targeting is working well but the lender of last resort function is yet to be fully understood.

Note: The Diamond-Dybvig view is that bank runs are inherent to the liquidity transformation carried out by banks. A bank transforms illiquid assets into liquid liabilities, subject to withdrawal.

Because of this maturity mismatch, if depositors suspect that others will run on the bank, it is optimal for each depositor to run to the bank to withdraw his or her deposit before the assets are exhausted. The bank run is not driven by some decline in the fundamentals of the bank. Depositors are spooked for some reason, panic, and attempt to withdraw their funds before others get in first. In this case, the provision of deposit insurance and lender of last resort facilities reassures depositors and stems the bank run

In the Kareken and Wallace model of bank runs, deposit insurance is problematic because of the incentives it gives to deposit taking institutions that are insured to take much greater risks. When there is deposit insurance, depositors don’t care about the greater risk in the portfolios of their banks. The greater risk taking leads to higher returns at no extra cost because if these risky investments do fail, the deposit insurance covers their losses

It is therefore necessary to regulate the portfolio of insured banks to ensure that they do not do this. That is the great dilemma for banking regulation because quasi-banks and other liquidity transformation intermediaries such as a Repo market spring up just outside the regulatory net.

Recent Comments