Claudia Goldin on Gender Equality in the Labor Market

02 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: Claudia Goldin, gender wage gap, wage gaps

The North–South theory of product life cycles

23 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in comparative institutional analysis, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, law and economics, managerial economics, organisational economics, property rights, survivor principle, theory of the firm Tags: entrepreneurial alertness, foreign direct investment, incomplete contracts, incomplete property rights, North-South product life cycle, product life cycles

Forecasts of the offshoring of service jobs, as an example, can be constituted into a theory of North-South product cycles. The North-South theory of the life cycle of products starts with their research and development and refinement by entrepreneurs in the advanced countries (the North) with some exporting (Grossman and Helpmann 1991a, 1991b). These innovations require resources to be invested with uncertain prospects of success. Entrepreneurs in the North compete to discover new technology-intensive products using the ample supply of R&D workers and human capital-rich workers in the industrialised countries (Grossman and Helpmann 1991a, 1991b).

As a new product matures and its production becomes more standardised, the bulk of its production can migrate to the less developed countries (the South) to take advantage of lower production costs, and these countries will become net exporters. In the South, entrepreneurs focus more on imitation. They invest resources in importing and learning the production processes developed and proven to be a success in the North (Grossman and Helpmann 1991a, 1991b).

The shifting of production of standardised products to lower-wage foreign locations will frequently be within the originating company via a foreign affiliate, because of uncertainties about property rights and contract enforcement institutions in the host countries, and only later to independent foreign firms (Antràs 2005). Within corporate hierarchies, the high-skilled managers in the developed countries will specialise in problem-solving and non-routine tasks. They will interact with middle managers and production workers in developing countries who perform the routine tasks (Antràs et al. 2006, 2008).

Contracts are typically incomplete either because they are difficult to write and/or because the court cannot enforce them. The World Trade Organization (2005, 2008) concluded that, for example, the location of offshored services depends on:

- labour costs,

- trade costs,

- the quality of institutions, particularly the legal framework,

- the tax and investment regime,

- the quality of infrastructure, particularly telecommunications, and

- skills, particularly language and computer skills.

Risks in contract negotiation and enforcement will influence which types of production is outsourced. Roughly one-third of world trade is infra-firm, and this intra-firm trade is concentrated in the capital-intensive industries because of the costs and risks of investing in contracting with arm’s-length suppliers (Antràs 2003). Considerations about R&D incentives, the availability of human capital and the quality of contract enforcement institutions weigh heavily on the development of new products and their initial and later locations of different stages of production.

Products are initially developed in the highly industrialised countries because their sophisticated legal systems allow contracts to be enforced. Even then, in industrialised countries, the difficulties of writing and enforcing complicated contracts over the quality of new products early in the product life cycle encourages firms to make those products internally within the firm. Early in the product life cycle, if sub-contractors were used for key imports, there would have to be continual renegotiation of contracts contracts to incorporate new innovations and learning by doing. As Antras says:

Global production networks necessarily entail intensive contracting between parties located in different countries and thus subject to distinct legal systems0

As the new product standardises, and product quality in consequence becomes easier to measure and contract over, initially the innovating firm will sub-contract within the industrialised country but in time will import from developing countries. In the first instance, these imports may be from affiliates established in the developing country to ensure greater control of product quality through direct ownership of the factory. As Antras says:

Firms contemplating doing business in a country with weak contracting institutions might decide to do so within firm boundaries to have more control.

The size and shape of the firm is a direct response to mitigate the costs of contracting over quality that is hard to measure and which is constantly changing early in the product cycle. By assigning ownership rights to the party undertaking the more important investment in quality early in the product life cycle, entrepreneurs and innovators can minimise the losses caused by lack of enforceable contracts over quality when quality is changing rapidly as the firm moves through the product life cycle.

Boeing blamed the delays on the delivery of the Dreamliner on an unwillingness of sub-contractors to stand by their contractual obligations. In response, Boeing acquired some of the key sub-contractors to ensure that they delivered as promised. This is a classic operation of the theory of the firm where the entrepreneur brings within the firm what is too expensive to transact on the market because of difficulties in measuring quality and defining and enforcing property rights over what has been contracted.

What if you could replace performance evaluations with four simple questions?

20 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, survivor principle Tags: Dilbert, performance reviews

at the end of every project, or once a quarter if employees have long-term assignments, managers would answer four simple questions — and only four. The first two are answered on a five-point scale, from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree;" the second two have yes or no options:

1. Given what I know of this person’s performance, and if it were my money, I would award this person the highest possible compensation increase and bonus.

2. Given what I know of this person’s performance, I would always want him or her on my team.

3. This person is at risk for low performance.

4. This person is ready for promotion today.

via What if you could replace performance evaluations with four simple questions? – The Washington Post.

What are the biggest workplace time wasters?

16 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics, survivor principle Tags: cyber loafing

The policy world and academia offer widely different opportunities for early career researchers

15 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

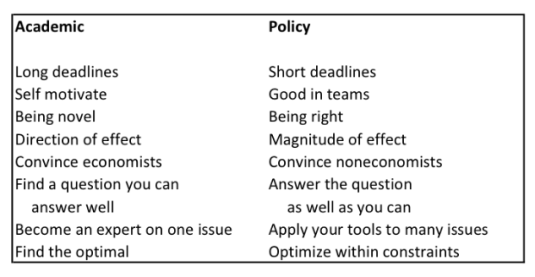

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of bureaucracy, economics of education, occupational choice, organisational economics, politics, Public Choice

Academia rewards findings that are different and unexpected. In policy it is more important to be right than novel—after all, millions of lives may be impacted by a policy decision. In academia, people argue a lot about the direction of an effect but very little about the magnitude: in policy it’s the reverse…

The Dunning Kruger effect versus non-directional coaching

12 Mar 2015 3 Comments

in economics of education, human capital, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: coaching, cognitive psychology, Dunning-Kruger effect, John Cleese, psychology of learning, Socratic questions

This seems to be a tension between the Dunning-Kruger effect on the principles of coaching as encompassed by its modern manifestation, non-directional coaching.

Under the modern fad of non-directional coaching, the coach asks open-ended questions which will elicit from the coached his or her own breakthroughs. Questions like what happened, what did you do then, is there another way will lead the student of the coach to reveal their knowledge within?

Psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger published a paper in which they described cognitive trait that quickly became known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. In a recent article, Dunning summarizes the effect as:

…incompetent people do not recognize—scratch that, cannot recognize—just how incompetent they are

He further explains:

What’s curious is that, in many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious.

Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.

People who lack the skill to do something also lack the skill to recognise that they don’t know how to do it and to develop the skill how to do it. Dunning also points out:

An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.

I’m bad at spelling, grammar and proofreading my own work. To know how skilled or unskilled I am at using the rules of grammar, I must have a good working knowledge of those rules to start with the self-assessed myself as not been good at grammar. This is impossible for me to find out for myself because I don’t know the rules of grammar to tell me that I don’t know the rules of grammar and to what extent I don’t know the rules of grammar. I have succumbed to the Dunning-Kruger Effect

“The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which unskilled people make poor decisions and reach erroneous conclusions, but their incompetence denies them the metacognitive ability to recognize their mistakes.

The unskilled therefore suffer from illusory superiority, rating their ability as above average, much higher than it actually is, while the highly skilled underrate their own abilities, suffering from illusory inferiority.

Actual competence may weaken self-confidence, as competent individuals may falsely assume that others have an equivalent understanding.

As Kruger and Dunning conclude, ‘the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others’. The effect is about paradoxical defects in cognitive ability, both in oneself and as one compares oneself to others.”

Poor performers fails to see the flaws in their thinking or the answers they lack. As Dunning explains:

A whole battery of studies conducted by myself and others have confirmed that people who don’t know much about a given set of cognitive, technical, or social skills tend to grossly overestimate their prowess and performance, whether it’s grammar, emotional intelligence, logical reasoning, firearm care and safety, debating, or financial knowledge.

College students who hand in exams that will earn them Ds and Fs tend to think their efforts will be worthy of far higher grades; low-performing chess players, bridge players, and medical students, and elderly people applying for a renewed driver’s license, similarly overestimate their competence by a long shot

Dunning and Kruger proposed that, for a given skill, incompetent people will:

- fail to recognize their own lack of skill;

- fail to recognize genuine skill in others;

- fail to recognize the extremity of their inadequacy; and

- recognize and acknowledge their own previous lack of skill, if they are exposed to training for that skill

Going back to my point about the modern trend in coaching of asking non-directive questions and open-ended questions and expecting the student to make their own breakthroughs, this contradicts the Dunning Kruger effect and the requirement that it be fixed through training. Coaching is not training; they are separate activities.

I was taught this non-directive coaching and went round the workplace asking questions of colleagues who are not economists using these open-ended questions of a coach. None of them made breakthroughs as a result of questions such as what happened, what happened then and other Socratic questions such as those below:

Conceptual clarification questions

Get them to think more about what exactly they are asking or thinking about. Prove the concepts behind their argument. Use basic ‘tell me more’ questions that get them to go deeper.

· Why are you saying that?

· What exactly does this mean?

· How does this relate to what we have been talking about?

· What is the nature of …?

· What do we already know about this?

· Can you give me an example?

· Are you saying … or … ?

· Can you rephrase that, please?

Probing their assumptions makes them think about the presuppositions and unquestioned beliefs on which they are founding their argument. This is shaking the bedrock and should get them really going!

· What else could we assume?

· You seem to be assuming … ?

· How did you choose those assumptions?

· Please explain why/how … ?

· How can you verify or disprove that assumption?

· What would happen if … ?

· Do you agree or disagree with … ?

Probing rationale, reasons and evidence

When they give a rationale for their arguments, dig into that reasoning rather than assuming it is a given. People often use un-thought-through or weakly-understood supports for their arguments.

· Why is that happening?

· How do you know this?

· Show me … ?

· Can you give me an example of that?

· What do you think causes … ?

· What is the nature of this?

· Are these reasons good enough?

· Would it stand up in court?

· How might it be refuted?

· How can I be sure of what you are saying?

· Why is … happening?

· Why? (keep asking it — you’ll never get past a few times)

· What evidence is there to support what you are saying?

· On what authority are you basing your argument?

Questioning viewpoints and perspectives

Most arguments are given from a particular position. So attack the position. Show that there are other, equally valid, viewpoints.

· Another way of looking at this is …, does this seem reasonable?

· What alternative ways of looking at this are there?

· Why it is … necessary?

· Who benefits from this?

· What is the difference between… and…?

· Why is it better than …?

· What are the strengths and weaknesses of…?

· How are … and … similar?

· What would … say about it?

· What if you compared … and … ?

· How could you look another way at this?

Probe implications and consequences

The argument that they give may have logical implications that can be forecast. Do these make sense? Are they desirable?

· Then what would happen?

· What are the consequences of that assumption?

· How could … be used to … ?

· What are the implications of … ?

· How does … affect … ?

· How does … fit with what we learned before?

· Why is … important?

· What is the best … ? Why?

And you can also get reflexive about the whole thing, turning the question in on itself. Use their attack against themselves. Bounce the ball back into their court, etc.

· What was the point of asking that question?

· Why do you think I asked this question?

· Am I making sense? Why not?

· What else might I ask?

· What does that mean?

Signs of poor management – Not listening and not making people feel valued

12 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

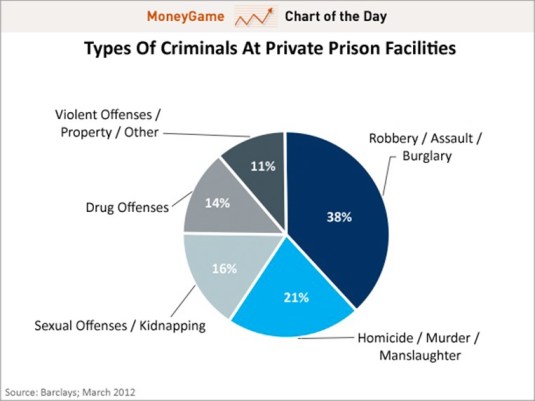

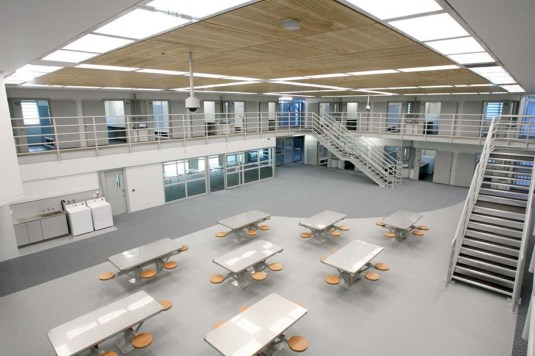

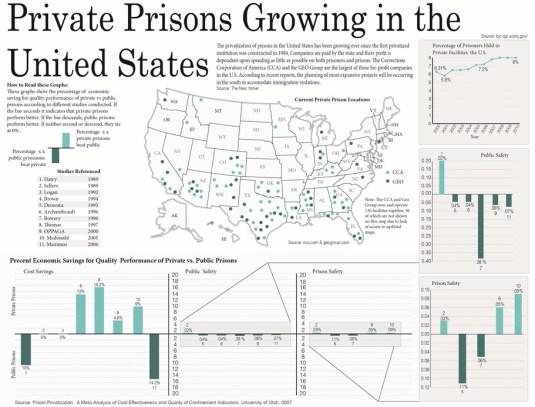

Security cameras in prison showers and the case for private prisons

06 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, entrepreneurship, law and economics, organisational economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: do gooders, law and order, prisons

I was listening to a radio show the other day on the introduction of close circuit television into New Zealand prisons that were to be monitored by both male and female guards. This is regarded as an indignity by some because these new close circuit cameras would be in showers and toilets.

The initial commentators on the radio programme immediately said they had watched plenty of TV programs where people were shanked in the showers.

The close circuit television was for the safety of prisoners. Close circuit cameras in all parts of prisons made prisons a safer place and that was that. It was the price of safety, especially for prisoners vulnerable to intimidation and sexual assault.

Greg Newbold, a New Zealand criminologist and an ex-prisoner in itself, then came on air to criticise the introduction of close circuit televisions in showers and other intimate areas such as toilets as an indignity on prisoners. Prisoners have a right to intimate privacy in his view. He said only 12 prisoners had been murdered in the New Zealand prisons since 1979.

Only 12 murders is 12 murders too many. Every one of those murders would have been subject of outrage about the failure of the prison administration from the bleeding hearts brigade.

The most interesting thing that Greg Newbold said on the radio was about how these close circuit television systems first emerged in prisons, initially in the USA.

Close circuit television systems will put throughout prisons initially in private prisons to avoid being sued for wrongful death and injury. The private prisons introduced this rather obvious security measure to reduce liability in the civil courts.

Public prisons are supposedly a safer place for prisoners to be if you listen to the bleeding hearts brigade and the Left over Left. Pubic prisons but never got around introducing what seems to me to be a rather basic security measure in confined areas of prisons. Close circuit television systems would protect both inmates and guards.

The different incentives facing public and hybrid prisons, in this case, exposure to litigation, is an illustration of the superior efficiency of private prisons.

Private prisons did something because it affects the bottom line. One way to reduce liability for deaths and injuries is prison security measures that reduce the number of deaths and injuries in prisons.

More importantly, private prisons have unforgiving critics in the form of the bleeding hearts brigade and Left over Left. No one on the Left will defend or protect a prison that is private from closure out of a knee-jerk defence of the public sector, and in particular, public-sector unions.

Oddly enough the only prison that the Left over Left want to close in New Zealand is the highest performing prison, Mt Eden, which happens to be privately run.

The main problem with private prisons is contracting over quality where it is difficult to define quality and measure performance against quality standards specified in a contract as Andrew Shleifer explains:

…critics of privatization often argue that private contractors would cut quality in the process of cutting costs because contracts do not adequately guard against this possibility

Privatisation for many government services is simply an extension of the make-or-buy decision. Every firm faces a make-or-buy decision – should the firm buy a production input from outside suppliers or should it make what it needs itself with existing or additional internal resources?

As any industry grows, there is more room for more specialised producers to supply to firms of all sizes at a lower cost than in-house production (Stigler 1951, 1987; Levy 1984). As an example, all with the largest firms intermittently hire legal, accounting and many other professional skills from specialists.

By contracting-out to these more specialised and niche suppliers, firms can enjoy all available economies of scale in production unless its needs are unique or the firm has some special competency in producing the input in-house (Lindsay and Maloney 1996; Shughart 1997; Roberts 2004). Firms in most industries capture all available economies of scale at relatively small sizes after which they have a long region of production where their marginal cost of further increases in production are constant (Stigler 1958; Lucas 1978; Barzel and Kochin 1992; Shughart 1997).

Put simply, an entrepreneur makes what he or she cannot buy at the quality preferred through contracting in market:

The case for in-house provision is generally stronger when non-contractible cost reductions have large deleterious effects on quality, when quality innovations are unimportant, and when corruption in government procurement is a severe problem. In contrast, the case for privatization is stronger when quality reducing cost reductions can be controlled through contract or competition, when quality innovations are important, and when patronage and powerful unions are a severe problem inside the government.

The way in which the market process dealt with chiselling on quality where quality reducing cost reductions where costly to control through contract or competition was the emergence of non-profit institutions. The competitive edge of these non-profit institutions was they had fewer incentives to dilute hard to measure qualities of the product transacted.

Any additional profits from this dilution of quality were not distributed to the owners because the non-profit organisation was either run by a charity or was owned mutually by the customers. The proceeds from cutting corners on quality could not be paid out to the owners in dividends because there were none.

Examples of non-profits competing successfully in the market are obvious, such as life insurance. Until recent decades, most life insurance companies were mutually owned by the policyholders. Life insurance companies were mutually owned as an assurance that no one could run off with the money by paying high dividends to the owners before policyholders died many years after they have paid their premiums.

Most private universities are run as non-profit institutions even when they are set up by private developers with profits in mind. The private university itself is owned by a charity with esteemed persons on the board to assure quality and probity. The active involvement of alumni is encouraged as a further guard of the future quality of the University from which they graduated. The private developers make their profit on the surrounding land as the university grows and prospers. Land grant universities in the USA may have operated this way.

Other examples of the emergence of non-profit institutions to assure quality in a competitive market are private schools, private hospitals, and private day care centres where concerns about the private provision of a quality service arise, with or without justification. Andrew Shleifer again:

…entrepreneurial not-for-profit firms can be more efficient than either the government or the for-profit private suppliers precisely … where soft incentives are desirable, and competitive and reputational mechanisms do not soften the incentives of private suppliers [to dilute quality].

Of course, any proper analysis must compare like with like and compare the dismal record of public prisons date in terms of prisoner and prison guard safety and preventing escapes with any scandals in the private prison systems. Few do that.

What do industrial and organisational psychologists help employers do?

03 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: Dilbert, industrial psychology

HT: sageassessments

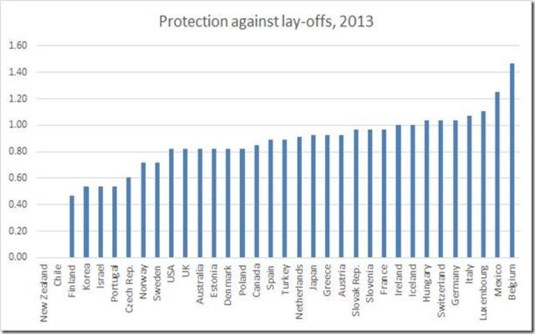

France, here the New Zealand labour market comes! The Employment Court’s long march to re-regulate

03 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, job search and matching, labour economics, law and economics, organisational economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: employment protection laws, France, The fatal conceit, vexatious litigation

If the Employment Court had its way, New Zealand case law under the Employment Relations Act regarding redundancies and layoffs would be as strict as those in France. As top employment lawyer Peter Cullen explained in the Dominion Post today:

Former Employment Court chief justice Tom Goddard said employees could not be made redundant unless the company would otherwise go to the wall.

The employer appealed.

The Court of Appeal said something quite different. Its view was that if a business could be run more efficiently without a particular position, then it was entitled to disestablish it.

The Court of Appeal made it plain that it would not critically examine the logic behind the employer disestablishing a role. If the reason behind the redundancy was genuine, that was all that really mattered. Of course a fair process and consultation ought to precede any decision, but the outcome nevertheless was that the position could go.

The Employment Court wanted the position to be the same as at that in France where layoffs are permissible only to avoid bankruptcy:

…firms still cannot lay off workers to improve competitiveness when the business is healthy; they can only make economic dismissals to preserve competitiveness when already in financial straits. In France, it ought to be legal to fix small problems before they become big.

This French standard of regulation of layoffs and redundancies, if it had survived on appeal, would have come as a surprise to many, including the OECD who rates New Zealanders having no regulation of layoffs in its Index of Employment Protection.

Source: OECD employment protection index.

But you can’t keep an activist Employment Court down. It’s next tactic was salami tactics. Chipping away at the right of the employer to run its business and decide how large its labour force is. Peter Cullen again with the Employment Court pretending it can second-guess entrepreneurial judgements and arithmetic:

In the case between Grace Team Accounting and employee Judith Brake, the Employment Court found that the decision to make Brake’s position redundant was based upon mistaken arithmetic. The Court of Appeal held that Brake’s redundancy amounted to an unjustified dismissal.

Next cab off the rank was requiring employers to give preference to redundant employees pretty much no matter what. Peter Cullen again:

In the case of Neil Wang and his employer the Hamilton Multicultural Services Trust, the trust encouraged Wang to apply for another role within the organisation.

However, the Employment Court said the trust should have considered whether they should have simply offered Wang the position without having to go through an application process.

The court found that even though the other role was not the same, it required the same skills and minimal retraining and so the trust should have simply given Wang the role.

It is standard in the redundancies and restructurings I’ve been involved with for non-managerial employees to go through internal reassignment panels. Some didn’t make it and were laid off.

It’s common for the managerial vacancies to be advertised externally so that redundant managers must compete with external applicants so that the workplace can renew itself. Quite a few managers don’t make it through this process because of the external competition.

This clear preference for existing employees is a major reregulation of the labour market. Now, every redundant employee can engage in vexatious litigation and squeeze a few thousand dollars extra out of the employer by threatening to go to the Employment Court for a second opinion on the entrepreneurial judgements of the employer. To save managerial time as well is legal fees, it’s cheaper for most employers to pay the redundant employee off with a small settlement.

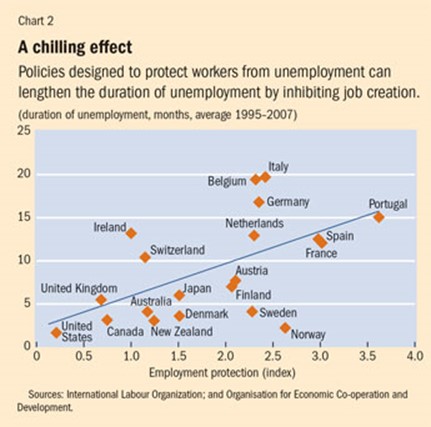

Anything that makes it more expensive to fire an employee makes it more expensive to hire an employee. This will reduce job creation in New Zealand now that the French standard applies:

…businesses remain obligated to assist laid-off employees in finding other jobs and in retraining them for their new positions – a distinctly French phenomenon. For businesses with more than 1,000 employees, this limbo period before dismissal can last from four to nine months.

Recent Comments