.@nzfamilies commission estimate of cost of zoning

11 Mar 2018 1 Comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking, urban economics Tags: housing affordability, land supply, zoning

Philip Payton Jr.: The Crusading Capitalist Who Outwitted New York’s Racist Landlords

08 Mar 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economic history, entrepreneurship, poverty and inequality, urban economics Tags: racial discrimination

Walter E. Williams: How urban economic policy creates a Ferguson and Baltimore

18 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, labour economics, law and economics, poverty and inequality, urban economics Tags: child poverty, crime and punishment, family poverty

Wooden skyscrapers could be the future for cities | The Economist

15 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, environmental economics, global warming, urban economics

The 30 Mile Zone That Explains Why Hollywood Exists

13 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in industrial organisation, labour economics, unions, urban economics Tags: Hollywood economics

Do-gooders want to introduce rent controls and security of tenure to restrain rapacious landlords further. Little wonder every 3rd Auckland rental property is sold and the tenants evicted every 2 years.

12 Feb 2018 1 Comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, urban economics

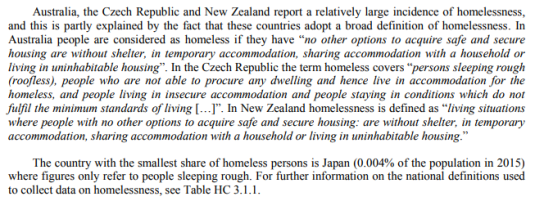

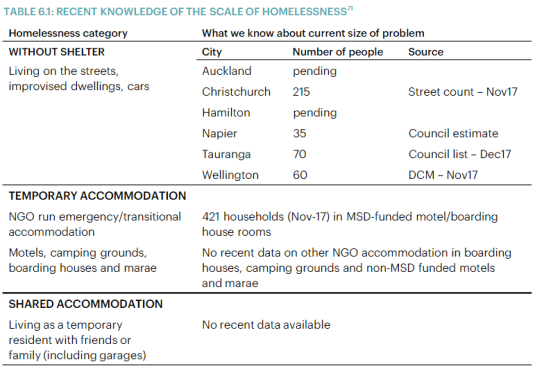

I thought there were 41,000 homeless

12 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, urban economics

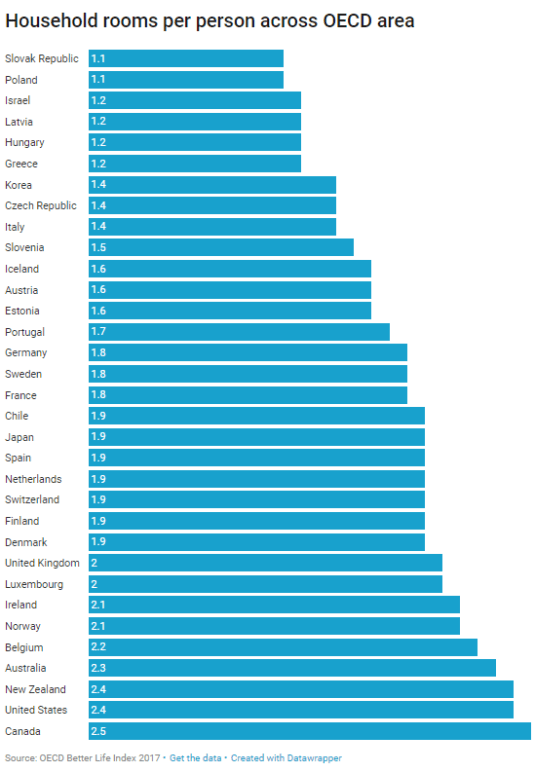

Many Kiwis think housing affordability is not that bad!?

09 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in politics - New Zealand, urban economics Tags: affordable housing, land supply

Coober Pedy is a town that is mostly underground. The YouTube clips dub it with American or British accents thus missing the marvellous Australian accent and vernacular of the local narrator

03 Feb 2018 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, urban economics

The locations of half of the Australian Population

08 Jan 2018 Leave a comment

in urban economics Tags: maps

Build More Housing! San Francisco’s YIMBY Movement Has a Plan to Solve the City’s Housing Cris

06 Jan 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of religion, Public Choice, rentseeking, urban economics Tags: land supply, NIMBYs, zoning

Why we live in Wellington; cheap housing, and safer too

30 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, urban economics

New Zealand sexes up the numbers on homelessness

16 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

in politics - New Zealand, poverty and inequality, urban economics

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD – Social Policy Division – Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Last updated on 24/07/2017 HC3.1 HOMELESS POPULATION

Recent Comments