The Great Alaska Pipeline

16 Aug 2021 Leave a comment

in economic history, energy economics Tags: Alaska

All to often the climate emergency is a truth emergency

18 Jul 2019 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of information, environmental economics, global warming, politics - USA Tags: Alaska, climate alarmism

Why did Russia sell Alaska to America? (Short Animated Documentary)

24 Jun 2019 Leave a comment

in economic history, international economics, politics - USA, Public Choice Tags: Alaska, Russia

Balto: The Canine Hero

10 Apr 2019 Leave a comment

in economic history, health economics Tags: Alaska

#nzeq Post-disaster labour market adjustment: Alaska in the pipeline era & Darwin after Cyclone Tracy

17 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of natural disasters, labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, transport economics, urban economics Tags: Alaska, Cyclone Tracy

Experiences from abroad suggest that labour markets have a history of rapid adaptation to regional surges in construction demand and that workers are prepared to tolerate lower quality housing provided there are compensating wage premiums.

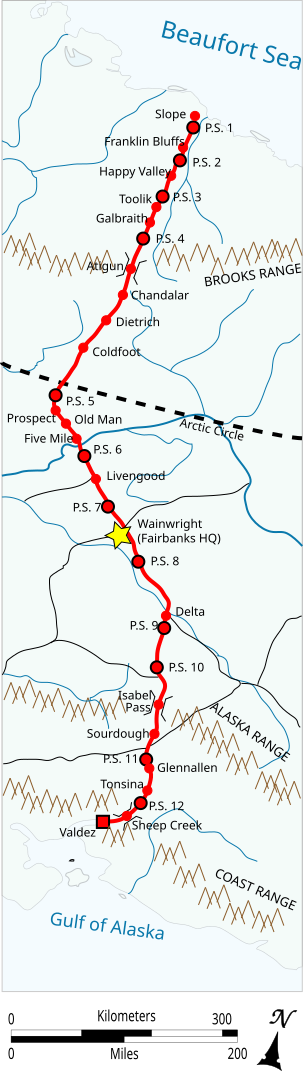

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline was the largest privately funded construction project to that time. Alaskan wages during the building period between 1974 and 1977 were very flexible in the construction and related industries.

Labour supply was responsive in terms of more hours worked per worker and more local workers entering the workforce with many others moved temporarily to Alaska even though the Alaskan climate and culture would not appeal to everyone.

The Alaskan labour force increased by 50%, from about 50,000 to about 90,000 workers, hours worked per week increased by about the same, and many people worked 2 jobs.

High school hours were moved to the morning so that students and their teachers could take an afternoon job in pipeline construction. There is hot beading of accommodation and a 1000% labour turnover rate at the local McDonald’s. By 1979, the Alaskan labour force returned pretty much to its preconstruction era size.

Moving to a region still prone to after-shocks also would not appeal to everyone. Many energy industry construction projects in modern times were completed in unappealing locations and extreme climates on land and sea.

As another and much nearer example, Cyclone Tracy destroyed about 60 per cent of the 8,000 houses in Darwin on 24 December 1974 and more than 30 per cent were severely damaged. Most of Darwin’s population of 48,000 people became homeless; 71 lives were lost.

After a mass evacuation of 35,000, Darwin’s population was 10,000 by 1 January 1975. Darwin’s population recovered to 30,000 by May 1975. This influx was dominated by newcomers, especially construction workers. Temporary housing, caravans, hotels and an ocean liner were all pushed into service.

When the Darwin Reconstruction Commission was wound up two years ahead of the initial reconstruction timeline on 12 April 1978, 3,000 new dwellings had been completed. By mid-1978, the city could again house its pre-Tracy population numbers. Darwin is now home for about 125,000 people.

Recent Comments