Bryce Edwards has shown in today’s column that he knows nothing about inequality in New Zealand, despite the statistics being at his fingertips:

Under capitalism there’s always going to be a war against the poor.

The process by which we divide up the resources of any society normally involves exploiting the majority for the benefit of the minority.

It’s called inequality. And this is how it is in New Zealand: those who have the most power look for ways to extract that money for themselves, or at least retain the status quo.

Against this are those who want to have a more equal society. It’s an age-old political issue, and one that has traditionally been at the heart of the left-right political divide.

In 2014 this concern about inequality has been a key feature of politics, underpinning much of what has occur…

Although the rich appear to have been winning for three decades in their ‘war against the poor’, perhaps the tide is turning?

There’s still every indication of severe poverty and inequality in this country.

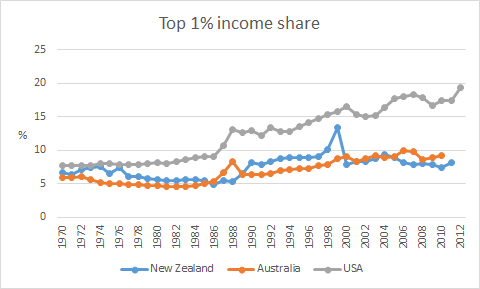

Firstly, inequality has not increased in New Zealand for at least 20 years when either measured in figure 1 by the Gini coefficient or in figure 2, the top 1% income shares. Both the Gini coefficient and the top 1% income shares have not risen for 20 years.

Figure 1: Gini coefficient New Zealand 1980-2015

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

Figure 2: Top 1% income shares, USA, New Zealand and Australia, 1970-2012

Source: top incomes database

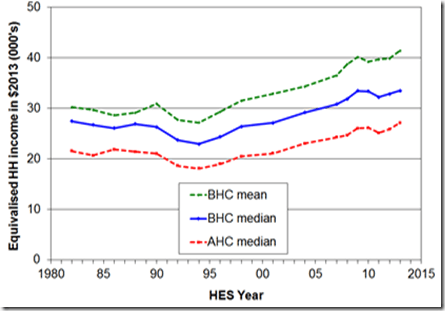

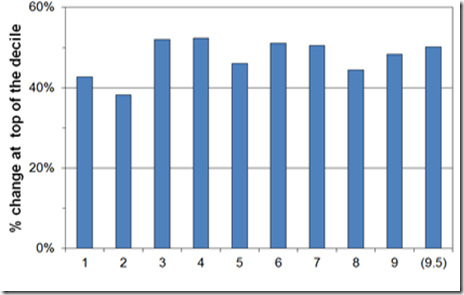

Secondly, the benefits of the economic boom that lasted 15 years from the early 1990s until the onset of the global financial crisis would spread broadly across all sections of the New Zealand community. As shown in figure 3, both before and after housing costs increased. As shown in figure 4, real household incomes increased pretty much evenly across all of the 10 income deciles between 1994 and 2013.

Figure 3: Real household income trends before housing costs (BHC) and after housing costs (AHC), 1982 to 2013 ($2013)

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

Figure 4: Real household incomes (BHC), changes for top of income deciles, 1994 to 2013

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

Thirdly, as shown in figure 5, between 1994 and 2010, real equivalised median household income rose 47% from 1994 to 2010; for Māori, this rise was 68%; for Pasifika, the rise was 77%. Median household income increases of nearly 50% in 16 years should be celebrated.

Figure 5: Real equivalised median household income (before housing costs) by ethnicity, 1988 to 2013 ($2013).

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

The massive improvements in Māori incomes since 1992 were based on rising Māori employment rates, fewer Māori on benefits, more Māori moving into higher paying jobs, and greater Māori educational attainment. Māori unemployment reached a 20-year low of 8 per cent from 2005 to 2008.

Over the last more than two decades in New Zealand, there has been sustained income growth spread across all of New Zealand society contrary to the warmed over Marxism of Bryce Edwards. Perry (2014) reviews the data every year for the Ministry of Social Development. He concluded that:

Overall, there is no evidence of any sustained rise or fall in inequality in the last two decades.

The level of household disposable income inequality in New Zealand is a little above the OECD median.

The share of total income received by the top 1% of individuals is at the low end of the OECD rankings.

Bryce Edwards’ analysis was in the typical Marxist tradition – it had no gender analysis. He failed to mention that New Zealand has the smallest gender wage gap of all the industrialised countries.

As he did not notice these great successes in household incomes, incomes of every decile, Māori economic development and the empowerment of women, Bryce Edwards had nothing to add in terms of either consolidating or improving on them.

Recent Comments