Why Bills of Rights

08 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, law and economics Tags: Bill of Rights, democracy, Justice Robert Jackson, rule of law

Unfettered power loses its shine when it must be shared with your opponents for more than a brief time

05 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, Federalism, James Buchanan, Public Choice Tags: democracy, Leftover Left, rotation of power, separation of powers

The rotation of power is common in democracies, and the worst rise to the top, so it is wise to design constitutional safeguards to minimise the damage done when those crazies to the right or left of you get their chance in office, as they will.

Too many policies and ideas of the Left assume that they are the face of the future, rather than just another political party that will hold power as often as not.

Privatisation and deregulation is a lot slower in a federal system with an effective upper house elected by proportional representation. Regulatory powers and public asset ownership is spread over different levels of federations, with different parties always in power at various levels at the same time, all worried about losing office by going to far away from what the majority wants.

The will of the people is constantly tested and measured in a federal system with elections at one level or another every year or so contested on a mix of local and national issues. Any failings of privatisation or deregulation in pioneering jurisdictions would quickly become apparent and would not be copied by the rest of the country. These errors could be undone where they originated by incoming progressive governments.

The Left may want to protect the rights of the unpopular and the unpleasant, and to want constitutional safeguards to slow an impassioned majority down is, in part, because they could be next if they lose the next election to the latest right-wing populist.

In a unitary unicameral parliament, those crazies to the right or left of you are tempered by an occasional general election only every 3 to 5 years. Little wonder that UK Labor reconsidered devolution, an assembly for London, and regional government after 15 years of Maggie Thatcher, good and hard, with her unfettered right to ask the house of commons to make or unmake any law whatsoever.

Developing positive alternatives on the Left includes what to do about the rotation of power and fettered versus unfettered parliamentary and executive power. The failure of the Left to develop its own constitutional political economy is a major strategic shortcoming. Frequenting wine bars, cafes and blogs muttering to each other ‘our day will come, our day will come’ is not enough.

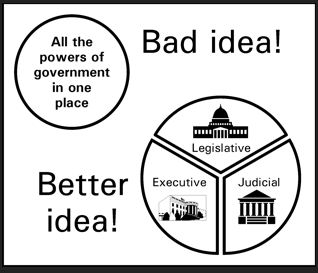

State power was something that the classical liberals feared, and the problem of constitutional design is insuring that such power would be effectively limited.

Sovereignty must be split among several levels of collective authority; federalism was designed to allow for a decentralization of coercive state power.

At each level of authority, separate functional branches of government were deliberately placed in continued tension, one with the other. The legislative branch is further restricted by the establishment of two strong houses, each of which organised on a separate principle of representation

The contribution of fox hunting to the development of English Constitutional Law

04 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

Thai Junta Revokes a Famed Academic’s Passport in Its Crackdown on Dissidents

11 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in politics Tags: democracy, military coup, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, rule of law, Thailand

An old graduate school mate of ours from our Japan days, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, a prominent Thai political scholar and outspoken opponent of the country’s coup, has had his passport revoked as part of the Thai junta’s on-going campaign against dissent.

He is based at Japan’s Kyoto University, and is expected to seek asylum in Japan.

via The Thai Junta Revokes a Famed Academic’s Passport in Its Crackdown on Dissidents | TIME.

Freedom of religion and equality before the law in a democracy

04 Jul 2014 4 Comments

in liberalism, politics - Australia, war and peace Tags: democracy, democratic equality, Freedom of religion, freedom of speech, rule of law

An individual’s religious beliefs does not excuse him from compliance with an otherwise valid law of general application prohibiting conduct that governments are free to regulate.

Allowing exceptions to every law or regulation that directly or indirectly affects religion would open the prospect of constitutionally required exemptions from legal obligations of almost every conceivable kind. Examples are compulsory military service, payment of taxes, polygamy, vaccination requirements, and child-neglect laws. some parliaments do provide exemptions and accommodations but that does not say they must.

Justice Frankfurter wrote in 1940:

conscientious scruples have not in the course of the long struggle for religious toleration relieved the individual from obedience to a general law not aimed at the promotion or restriction of religious beliefs.

The mere possession of religious convictions which contradict the relevant concerns of political society does not relieve the citizen from the discharge of political responsibilities

Religious freedom bars laws that prohibit:

- the holding of a religious belief,

- the right to communicate those beliefs to others, and

- the right of parents to direct the education of their children.

This approach also has the advantage of not placing courts into the position of having to determine the importance of a particular belief in a religion or the plausibility of a religious claim when weighing it against other government interests and the objectives of the disputed law.

It might be said that there should be a compelling government interest before a religious objection can be overridden. Deciding what is a compelling government interest raises questions of public policy.

Men and women decide what is more or less important in the course of making legislation goes to the very heart of democratic decision-making. This clash of opinions and visions of the good society and what laws should be passed or not are all resolved peacefully through the ballot box and free speech even in the most desperate times.

This is not to say that a parliament may if it wishes exempt people from certain obligations on the basis of religious objections or making other accommodations. What it does require is that religions take their chances in democratic politics like the rest of us when seeking exemptions from a law.

Minorities with strong feelings about an issue regularly prevail in legislative battles because they are willing to vote as a block on one issue and trade their block support with other groups in the society to assemble the necessary majority for what they want.

Indeed, a major discontent with contemporary democratic politics is minorities and special interests have too much say, not too little.

It is up to the political process to decide whether to disadvantage those religious practices that are not widely engaged in, but that unavoidable consequence of democratic government must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself. To quote Frankfurter again:

Its essence is freedom from conformity to religious dogma, not freedom from conformity to law because of religious dogma.

Religious loyalties may be exercised without hindrance from the state, not the state may not exercise that which except by leave of religious loyalties is within the domain of temporal power. Otherwise each individual could set up his own censor against obedience to laws conscientiously deemed for the public good by those whose business it is to make laws…

The validity of secular laws cannot be measured by their conformity to religious doctrines. It is only in a theocratic state that ecclesiastical doctrines measure legal right or wrong

Jon Elster on the dangers of majority rule

28 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy Tags: democracy, majoritarianism

Firstly, majority government will always be tempted to manipulate political rights to increase its chances of re-election. If it is free to change the timing of the election, for instance, it may choose a moment when economic conjunctures are favourable.

Secondly, a majority may set aside the rule of law under the sway of a standing interest or a momentary passion. This was Madison’s main worry:

In all cases where a majority are united by a common interest or passion, the rights of the minority are in danger.

Thirdly, here is the case of a popular majority acting (through its representatives) to further its economic interests.

Fourthly, there is the case of a popular majority acting (through its representatives) under a sudden impulse, a momentary passion. There are references by American founders such as Randolph to "the turbulence and follies of " and "the fury of democracy," by Hamilton to "the popular passions [which] spread like wild fire, and become irresistable," and by Madison to "fickleness and passion," and "the turbulency and violence of unruly passion."

Fifthly, there is the case of a popular majority acting (through its representatives) from a standing, permanent passion. This is different from a majority passion that is "sudden," "fickle," "unruly," and the like. The more permanent passions and prejudices that might fashion the will of the majority is in the late twentieth century the outstanding danger of majority rule. But this can be majoritarianism based on religious, ethnic and racial divides that lead to a permanent majority and a permanent minority.

There are four counter-majoritarian, rights-protecting devices: constitutional entrenchment of rights, judicial review, separation of powers and checks and balances.

Recent Comments