While there is a vast literature documenting the large private returns from education and on-the-job human capital (Card 1999; Rubenstein and Weiss 2007; Almeida and Carneiro 2008), evidence of human capital spillovers is limited. Many studies find little evidence of spillovers from education (Lange and Topel (2005), Ciccone and Peri (2006)). Studies even struggle to find small spillovers from another year in high school (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001). Differences in human capital also explain only a small part of cross-national differences in incomes per capita (Hsieh and Klenow 2010; Parente and Prescott 2000, 2005).

The R&D industries offer a case study of the likely size of skills spillovers from worker mobility from large firms. The mobility of technical personnel and the human capital embodied in them across R&D firms is a substantial source of knowledge transfer (Møen 2005). For there to be a spillover, the new employer must pay recruits less than the value added by the job experience and skills they bring to the fold.

A key advantage of studying the mobility of R&D workers for skills spillovers is these industries are populated with many spin-offs founded by the ex-employees of larger firms. R&D spin-offs tend to be larger on average that other new firms and initially employ more advanced, more experienced workers and more technical specialists than do other new firms (Andersson and Klepper 2013).

Capturing the value of skills spillovers from job-hopping is a major business opportunity. The efforts of entrepreneurs to create and enforce property rights over information and other resources as their value increases are central to the organisation of both markets and firms.

A litmus test for the capture of the value of skills spillover is whether wages adjust in line with evolving career opportunities. Becker (2007, p. 134) explains this process of market adaptation and entrepreneurship as follows:

Firms introducing innovations are alleged to be forced to share their knowledge with competitors through the bidding away of employees who are privy to their secrets. This may well be a common practice, but if employees benefit from access to saleable information about secrets, they would be willing to work more cheaply than otherwise.

Møen (2005), Magnani (2006) and Maliranta, Mohnen and Rouvinen (2009) found that employers capture much of the skills spillovers to others by paying R&D workers less early in their careers; later employers pay higher wages to reflect the valued added by the human capital that these R&D recruits bring.

Andersson, Freedman, Haltiwanger, Lane and Shaw (2009) found that software firms in markets with large returns from product breakthroughs pay higher starting salaries to attract star employees. Accounting and legal firms and sports teams also pay more to recruit and retain top performers (Wezel, Cattini and Pennings 2006; Campbell, Ganco, Franco and Agarwal 2012; Rosen 2001).

Employers balance skills and knowledge acquisition through recruitment with in-house development of skills and knowledge. Mason and Nohara (2010) did not find ‘any evidence’ that the external experience of scientists and engineers is any more valuable to firms than is their internal experience.

Firms will pay a wage that equalises the returns on skills acquisition through recruitment with the returns on investing in in-house training. This equalisation of the returns between internal and external sources of skills and knowledge is consistent with competition penalising firms that pay too much or too little for inputs and rewarding entrepreneurs for superior alertness to new opportunities.

The option value of founding or working for a spin-off is also captured in the wages of R&D workers (Kitch 1980; Pakes and Nitzan 1983). Central to a spin-off is carrying on with new ideas and prototypes that the leaving employees judged to be under-valued by the parent firm and they want to build on at their own entrepreneurial risk (Klepper and Sleeper 2005; Klepper 2007).

Large firms are known for incremental innovations while small firms pioneer product break-troughs whose prospects were not as well valued inside large hierarchies (Baumol 2002, 2005; Audretsch and Thurik 2003). Many R&D spin-offs continue with emerging ideas and products that their parents were in the process of abandoning (Hellmann 2007; Chatetterjee and Rossi-Hansberg 2012; Klepper and Thompson 2010). One reason is the developing idea does not fit in with the risk profile and skills of the parent so many spin-offs are friendly (Fallick, Fleischman, and Rebitzer 2006; Chen and Thompson 2011).

Founding or working for a spin-off or start-up is a real prospect. In many innovative industries, upwards of 20 percent of new entrants are intra-industry spinoffs; these firms outperform other new entrants and disproportionately populate the ranks of industry leaders (Klepper and Thompson 2010).

The evidence of large firms spawning more entrepreneurs among scientists and engineers is mixed. Large parent firm size reduces both the probability of leaving, and more so, the probability of leaving to found a spin-off (Andersson and Klepper 2013; Sørensen 2007; Sørensen and Philipps 2011). Spin-offs are less likely from large parents because more of the skills and experience accumulated within large firms is firm-specific human capital and is therefore less mobile into a spin-off.

Scientists and engineers who worked in small firms are ‘far more likely’ to found a spin-off than are their large firm counterparts, and their spin-offs are more likely to be a success (Elfenbein, Hamilton and Zenger 2010; Sørensen and Phillips 2011). Working in smaller firms allows spin-off minded employees to gain the balance and wide array of technical knowledge and management skills that are prized in entrepreneurship (Elfenbein, Hamilton and Zenger 2010; Lazear 2004, 2005).

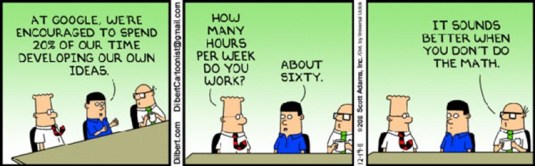

Working in managerial hierarchies works against founding a spin-off. Tåg, Åstebro and Thompson (2013) found that conditional on size, employees in firms with more layers of management are less likely to enter entrepreneurship, self-employing or quit to go to another firm. They attributed this to the employees in firms with fewer management layers developing a broader range of skills; multiple layers of management offering more promotion opportunities; and skill mismatch is less problematic in more hierarchical firms because there are more chances to move. The higher pay and better career opportunities in larger firms reduces job quits, and with it, skills spillovers and spin-offs.

The wage adjustments for current skills and knowledge transfer opportunities to future employers, start-ups and spin-offs are large. New science graduates accept 20 per cent less in starting pay to work where they can publish more in their own names (Stern 2004).

Scientists and engineers working in R&D accept 20 per cent less pay than other scientists and engineers who work in technical and managerial occupations to secure this more interesting work (Dupuy and Smits 2010). Gibbs (2006) suggested that the U.S. Department of Defense is able to recruit and retain engineers and scientists on low pay because they offer work on some of the most advanced technical research in the world.

Employers who pay full value in wages, share options, learning and R&D opportunities in exchange for the labour and human capital of employees are not benefiting from a skills spillover.

The evidence just reviewed identifies market processes that minimise skills spillovers from large R&D firms to spin-offs. Large firms train their employees in skills that are more often firm-specific and adjust wages to account for the career opportunities that might arise from on-the-job training that is more mobile. The employees of larger firms have longer job tenures in part because their human capital is less mobile.

Recent Comments