.

George Stigler on the extensive influence of economists on public policy

20 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in George Stigler, history of economic thought, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: evidence-based policy, expressive politics, expressive voting, intellectuals, politics of reform, rational ignorance, rational irrationality

How much of the political spectrum is neoliberal (and under the Svengali influence of the @MontPelerinSoc)?

06 Oct 2014 1 Comment

in liberalism Tags: conspiracy theories, Eric Crampton, intellectuals, Leftover Left, Mont Pelerin Society, neoliberalism, progressive left, Thomas Sowell, Twitter left

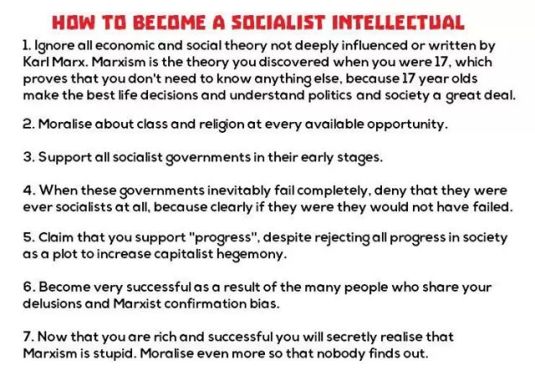

When I feud with strangers on other blogs about neoliberalism, I often asked them is to nominate which parties are neoliberal. Obviously the right-wing parties are neoliberal.

What is routine, however, is for this remnant of the Left over Left to nominate the Labour Party as a cauldron of neoliberalism as well. Tony Blair, Bob Hawke, and Paul Keating are hate figures as is Roger Douglas in New Zealand.

Neoliberalism is more about smearing labour parties than the right-wing parties, and, in particular, factional enemies further to the right with you on the old Left. Looks like to be a neoliberal is what it was like to be a capitalist running dog in the days of the cultural revolution.

These days it’s quite common to nominate the Mont Pelerin Society as the global ringmaster of neoliberalism.

As global ringmasters go, they have a crap website. The super profits of supreme power should at least extend to a decent website.

Eric Crampton was tweeting live from his first meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society a few weeks ago. I asked him how did it feel to be in the inner circles of supreme power. His tweet was they must hold all the conspiratorial meetings in side rooms because he did not feel any more powerful than the previous day at his desk at his University

No one had ever heard of the Mont Pelerin society until the Twitter Left put it at the centre of a global conspiracy.

No one had ever heard of the Mont Pelerin society until the Twitter Left put it at the centre of a global conspiracy.

It is much easier to do to explain your defeat at elections on a conspiracy, rather than on your ideas having been tried and failed time and again.

These allegations of a secret conspiracy led by the Mont Pelerin society is a rarity in the stock and fair of conspiracy theories. The leader of the conspiracy is actually unknown. Most conspiracy theories allege that the secret machinations are by relatively well-known people you are trying to smear or don’t like.

These allegations of a global conspiracy led by academics is the ultimate ego trip by proxy. Academics dream of supreme power. When they do not have this power themselves, they fantasise that the right-wingers at the other end of the corridor at their university have it instead.

Reasonable and unreasonable wariness of intellectuals

29 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics, economics of education, personnel economics Tags: intellectuals, Richard Posner, Thomas Sowell

Academics and their bias against the market

19 Mar 2014 1 Comment

in F.A. Hayek, market efficiency, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: academic bias, compensating differences, Hayek, intellectuals, Richard Posner, Robert Nozick, Schumpeter

The expansion of jobs for graduates from the 1960s onwards increased the choices for well-educated people more disposed to the market of working outside the teaching profession. Those left behind in academia were even more of the Leftist persuasion than earlier in the 20th century.

Dan Klein showed that in the hard sciences, there were 159 Democrats and 16 Republicans at UC-Berkley. Similar at Stanford. No registered Republicans in the sociology department and one each in the history and music departments. For UC-Berkeley, an overall Democrat:Republican ratio of 9.9:1. For Stanford, an overall D:R ratio of 7.6:1. Registered Democrats easily outnumber registered Republicans in most economics departments in the USA. The registered Democrat to Republican ratio in sociology departments is 44:1! For the humanities overall, only 10 to 1.

The left-wing bias of universities is no surprise, given Hayek’s 1948 analysis of intellectuals in light of opportunities available to people of varying talents:

- exceptionally intelligent people who favour the market tend to find opportunities for professional and financial success outside the universities in the business or professional world; and

- those who are highly intelligent but more ill-disposed toward the market are more likely to choose an academic career.

People are guided into different occupations based on their net agreeableness and disagreeableness including any personal distaste that they might have for different jobs and careers. There is growing evidence of the role of personality traits in occupational choice and career success.

The theories of occupational choice, compensating differentials and the division of labour suggest plenty of market opportunities both for caring people and for the more selfish rest of us:

- Personalities with a high degree of openness are strongly over-represented in creative, theoretical fields such as writing, the arts, and pure science, and under-represented in practical, detail-oriented fields such as business, police work and manual labour.

- High extraversion is over-represented in people-oriented fields like sales and business and under-represented in fields such as accounting and library work.

- High agreeableness is over-represented in caring fields like teaching, nursing, religion and counselling, and under-represented in pure science, engineering and law.

Schumpeter explained in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy that it is “the absence of direct responsibility for practical affairs” that distinguishes the academic intellectual from others “who wield the power of the spoken and the written word.”

Schumpeter and Robert Nozick argued that intellectuals were bitter that the skills so well-rewarded at school and at university with top grades were less well-rewarded in the market.

- For Nozick, the intellectual wants the whole society to be a school writ large, to be like the environment where he or she did so well and was so well appreciated.

- For Schumpeter, the intellectual’s main chance of asserting himself lies in his actual or potential nuisance value.

Richard Posner also had little time for academics who say they speak truth to power:

- The individuals who do so do it with the quality of a risk-free lark.

- Academics, far from being marginalized outsiders, are insiders with the security of well-paid jobs from which they can be fired with difficulty.

- Academics flatter themselves that they are lonely, independent seekers of truth, living at the edge.

- Most academics take no risks in expressing conventional left-leaning (or politically correct) views to the public, which is part of the reason they are not regarded with much seriousness by the general public.

George Stigler on the Svengali influence of economists on public policy and politicians

13 Mar 2014 3 Comments

in economics, George Stigler Tags: george stigler, intellectuals

Some regard economists as rather too influential over public policy – politicians seem to fall under their (two-handed) spell. I found this out when strangers would walk up to me at parties and blame me for the latest economic reforms they did not like. They go into offensive mode without even introducing themselves or knowing my name.

George Stigler argued that ideas about economic reform needed to wait for a market.

Stigler contended that economists exert a minor and scarcely detectable independent influence on the societies in which they live. As is well known, Stigler in the 1970s toasted Milton Friedman at a dinner in his honour by saying: “Milton, if you hadn’t been born, it wouldn’t have made any difference.”

Stigler said that if Richard Cobden had spoken only Yiddish, and with a stammer, and Robert Peel had been a narrow, stupid man, England would have still have repealed the corn laws. It would still have moved towards free trade in grain as its agricultural classes declined and its manufacturing and commercial classes grew in the 1840s onwards because of the industrial revolution.

As Stigler noted, when their day comes, economists seem to be the leaders of public opinion. But when the views of economists are not so congenial to the current requirements of special interest groups, these economists are left to be the writers of letters to the editor in provincial newspapers.

These days, they would post an angry blog.

Recent Comments