Lost on the woke

29 Feb 2020 Leave a comment

in liberalism, libertarianism Tags: Age of Enlightenment, free speech, JS Mill

Excellent JS Mill quotes on the market for ideas

21 May 2017 Leave a comment

in liberalism Tags: free speech, JS Mill, political correctness

The response of biologists to creation theory as compared to climate alarmism

20 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of education, environmental economics, global warming, movies Tags: climate alarmism, conjecture and refutation, Inherit the Wind, JS Mill, persuasion, Socratic questions

Biologists spent great effort over many decades to rebut creation science is a cold methodical manner designed to change minds through facts and reasoned arguments. Insults and conceit give peoples excuses to not listen.

Labels like denier and alarmist are not conducive for scientists to change their minds or decide they were right in the first place, and that such unpleasantness encourages many to choose other careers or fields of study.

It is better to ask your interlocutor to think more deeply about this or that point that is in debate. Look for common ground that already exists and for a growing number of important anomalies and puzzles their current way of thinking cannot explain. Knowledge grows through critical discussion, not by consensus and agreement.

J.S. Mill pointed out that critics who are totally wrong still add value because they keep you on your toes and sharpened both your argument and the communication of your message.

If the righteous majority silences or ignores its opponents, it will never have to defend its belief and over time will forget the arguments for it.

As well as losing its grasp of the arguments for its belief, J.S. Mill adds that the majority will in due course even lose a sense of the real meaning and substance of its belief.

What earlier may have been a vital belief will be reduced in time to a series of phrases retained by rote. The belief will be held as a dead dogma rather than as a living truth.

Beliefs held like this are extremely vulnerable to serious opposition when it is eventually encountered. They are more likely to collapse because their supporters do not know how to defend them or even what they really mean.

J.S. Mill’s scenarios involves both parties of opinion, majority and minority, having a portion of the truth but not the whole of it. He regards this as the most common of the three scenarios, and his argument here is very simple.

To enlarge its grasp of the truth the majority must encourage the minority to express its partially truthful view.

Three scenarios – the majority is wrong, partly wrong, or totally right – exhaust for Mill the possible permutations on the distribution of truth, and he holds that in each case the search for truth is best served by allowing free discussion.

Mill thinks history repeatedly demonstrates this process at work and offered Christianity as an illustrative example. By suppressing opposition to it over the centuries Christians ironically weakened rather than strengthened Christian belief, and Mill thinks this explains the decline of Christianity in the modern world. They forgot why they were Christians.

Going on about how climate science is settled and the debate is over is bad tactics for the climate alarmists.

Attempts to close the debate this way provokes suspicion among those who expect some attempt to persuade them rather than to instruct them from on high.

Presumptuousness is never a good influencing strategy nor is dismissiveness. Listen here you stupid dupe of corrupt corporate lackeys converts few.

Most know that the defining feature of the growth of knowledge is knowledge grows and that is often by displacing the received wisdom. These instincts come well before any knowledge is required by the philosophy and sociology of science.

Darrow’s polite and careful cross-examination of Bryan in that great movie Inherit the Wind persuaded many to reject religious-based opposition to the theory of evolution. He asked questions and was very polite. The movie was Spencer Tracy at his finest and in black and white.

Who do members of parliament represent?

28 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, Federalism, James Buchanan, Joseph Schumpeter, Public Choice Tags: consititutional design, Edmund Burke, federalism, James Madison, Jospeh Schumpeter, JS Mill, theories of representation

The theoretical literature on political representation focused on whether representatives should act as delegates or as trustees. James Madison articulated a delegate conception of representation. Representatives who are delegates simply follow the expressed preferences of their constituents.

The classical liberals of the 18th century were highly sceptical about the capability and willingness of politics and politicians to further the interests of the ordinary citizen, and thought the political direction of resource allocation retards rather than facilitates economic progress.

Governments were considered to be institutions to be protected from but made necessary by the elementary fact that all persons are not angels. Constitutions were a means to constrain collective authority. The problem of constitutional design was ensuring that government powers would be effectively limited.

- Sovereignty was split among several levels of collective authority; federalism was designed to allow for a deconcentration or decentralization of coercive state power.

- At each level of authority, separate branches of government were deliberately placed in continued tension, one with another.

- The dominant legislative branch was further restricted by the constitutional establishment of two houses bodies, each of which was elected on a separate principle of representation.

These constitutions were designed and put in place by the classical liberals to check or constrain the power of the state over individuals. The motivating force was never one of making government work better or even of insuring that all interests were more fully represented.

Members of parliament as trustees are representatives who follow their own understanding of the best action to pursue in another view. As Edmund Burke wrote:

Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests; which interests each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates; but parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole; where, not local purposes, not local prejudices ought to guide, but the general good, resulting from the general reason of the whole.

You choose a member indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of parliament. …

Our representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion.

Burke does not seem to be a fan of federalism and vote trading to protect minorities. Madison liked conflict and tension as a constraint of power and the size of government.

Schumpeter disputed that democracy was a process by which the electorate identified the common good, and that politicians carried this out:

• The people’s ignorance and superficiality meant that they were manipulated by politicians who set the agenda.

• Democracy is the mechanism for competition between leaders.

• Although periodic votes legitimise governments and keep them accountable, the policy program is very much seen as their own and not that of the people, and the participatory role for individuals is usually severely limited.

Modern democracy is government subject to electoral checks. John Stuart Mill had sympathy for this view that parliaments are best suited to be places of public debate on the various opinions held by the population and to act as watchdogs of the professionals who create and administer laws and policy:

Their part is to indicate wants, to be an organ for popular demands, and a place of adverse discussion for all opinions relating to public matters, both great and small; and, along with this, to check by criticism, and eventually by withdrawing their support, those high public officers who really conduct the public business, or who appoint those by whom it is conducted

Representative democracy has the advantage of allowing the community to rely in its decision-making on the contributions of individuals with special qualifications of intelligence or character. Representative democracy makes a more effective use of resources within the citizenry to advance the common good.

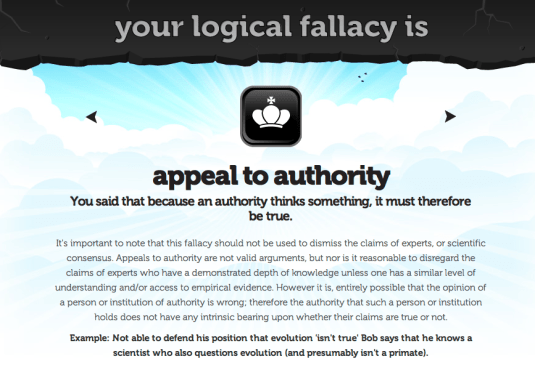

One of the troubling aspects of climate alarmism is its repeated appeals to authority. Rather odd for a bunch left-wingers trying to overthrow the status quo and the established order.

One of the troubling aspects of climate alarmism is its repeated appeals to authority. Rather odd for a bunch left-wingers trying to overthrow the status quo and the established order.

Recent Comments