New Zealand has the highest minimum wage in the world

19 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage, Uncategorized Tags: minimum wage, offsetting behaviour, Richard McKenzie, unintended consequences

John Schmitt lists 11 margins along which a minimum wage might cause changes:

- Reduction in hours worked (because firms faced with a higher minimum wage trim back on the hours they want)

- Reduction in non-wage benefits (to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage)

- Reduction in money spent on training (again, to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage)

- Change in composition of the workforce (that is, hiring additional workers with middle or higher skill levels, and fewer of those minimum wage workers with lower skill levels)

- Higher prices (passing the cost of the higher minimum wage on to consumers)

- Improvements in efficient use of labour (in a model where employers are not always at the peak level of efficiency, a higher cost of labour might give them a push to be more efficient)

- “Efficiency wage” responses from workers (when workers are paid more, they have a greater incentive to keep their jobs, and thus may work harder and shirk less)

- Wage compression (minimum wage workers get more, but those above them on the wage scale may not get as much as they otherwise would)

- Reduction in profits (higher costs of minimum wage workers reduces profits)

- Increase in demand (a higher minimum wage boosts buying power in overall economy)

- Reduced turnover (a higher minimum wage makes a stronger bond between employer and workers, and gives employers more reason to train and hold on to workers)

Richard McKenzie argues that the biggest impact of a minimum wage increase is reductions to paid and unpaid benefits for minimum wage workers, including health insurance, store discounts, free food, flexible scheduling, and job security resulting from higher-skilled workers drawn to the higher minimum wage jobs:

- Masanori Hashimot found that under the 1967 minimum-wage hike, workers gained 32 cents in money income but lost 41 cents per hour in training—a net loss of 9 cents an hour in full-income compensation. Several other researchers in independently completed studies found more evidence that a hike in the minimum wage undercuts on-the-job training and undermines covered workers’ long-term income growth.

- Walter Wessels found that the minimum wage caused retail establishments in New York to increase work demands by cutting back on the number of workers and giving workers fewer hours to do the same work.

- Belton Fleisher, L. F. Dunn, and William Alpert found that minimum-wage increases lead to large reductions in fringe benefits and to worsening working conditions.

- Mindy Marks found that workers covered by the federal minimum-wage law were also more likely to work part time, given that part-time workers can be excluded from employer-provided health insurance plans.

McKenzie also argued that if the minimum wage does not cause employers to make substantial reductions in fringe benefits and increases in work demands, then an increased minimum should cause

(1) an increase in the labour-force-participation rates of covered workers (because workers would be moving up their supply of labour curves),

(2) a reduction in the rate at which covered workers quit their jobs (because their jobs would then be more attractive), and

(3) a significant increase in prices of production processes heavily dependent on covered minimum-wage workers.

Wessels found that minimum-wage increases had exactly the opposite effect:

(1) participation rates went down,

(2) quit rates went up, and

(3) prices did not rise appreciably—which are findings consistent only with the view that minimum-wage increases make workers worse off.

McKenzie was the first economist to argue that a minimum wage increase may actually reduce the labour supply of menial workers. Employment in menial jobs may go down slightly in the face of minimum-wage increases not so much because the employers don’t want to offer the jobs, but because fewer workers want these menial jobs that are offered.

The repackaging of monetary and non-monetary benefits, greater work intensities and fewer training opportunities make these jobs less attractive relative to their other options. This reduction in labour supply by low skilled workers is why the voluntary quit rate among low-wage workers goes up, not down, after a minimum wage increase. As McKenzie explains

Economists almost uniformly argue that minimum wage laws benefit some workers at the expense of other workers.

This argument is implicitly founded on the assumption that money wages are the only form of labour compensation.

Based on the more realistic assumption that labour is paid in many different ways, the analysis of this paper demonstrates that all labourers within a perfectly competitive labour market are adversely affected by minimum wages.

Although employment opportunities are reduced by such laws, affected labour markets clear. Conventional analysis of the effect of minimum wages on monopsony markets is also upset by the model developed.

McKenzie argues that not accounting for offsetting behaviour led to a fundamental misinterpretation in the empirical literature on the minimum wage. That literature shows that small increases in the minimum wages does not seem to affect employment and unemployment by that much.

…. wage income is not the only form of compensation with which employers pay their workers. Also in the mix are fringe benefits, relaxed work demands, workplace ambiance, respect, schedule flexibility, job security and hours of work.

Employers compete with one another to reduce their labour costs for unskilled workers, while unskilled workers compete for the available unskilled jobs — with an eye on the total value of the compensation package. With a minimum-wage increase, employers will move to cut labour costs by reducing fringe benefits and increasing work demands…

Proponents and opponents of minimum-wage hikes do not seem to realize that the tiny employment effects consistently found across numerous studies provide the strongest evidence available that increases in the minimum wage have been largely neutralized by cost savings on fringe benefits and increased work demands and the cost savings from the more obscure and hard-to-measure cuts in nonmoney compensation.

McKenzie is correct in arguing that the empirical literature on the minimum wage is dewy-eyed. The first assumption about any regulation is the market will offset it significantly. In the course of undoing the direct effects of the regulation, there will be unintended consequences such as the remixing of wage and nonwage components of remuneration packages of low skilled workers covered by the minimum wage.

Two impossible things alert: supporting both a higher youth minimum wage and a larger youth wage subsidy

07 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage Tags: minimum wage, wage subsidy

The New Zealand Labour Party is one of many parties on the Left and Right that support youth wage subsidies as a way of making it cheaper for employers to hire teenagers. The rationale is if you make it cheaper to hire teenagers, employers will hire more of them.

New Zealand Labour Party is one of many parties on the Left and occasionally on the Right that supports a youth minimum wage

Supporters of youth minimum wages do not believe that making teenagers more expensive to hire will harm their employment prospects.

Indeed, it is even argued that a higher minimum wage will increase the employment of teenagers and adults.

Minimum wages are supported because the price of labour doesn’t matter that much to the employment prospects of teenagers and adults.

Wage subsidies is supported because the price of labour is important to the employment prospects of teenagers and adults.

Teen employment and the minimum wage: sixty years of U.S. experience

02 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: minimum wage

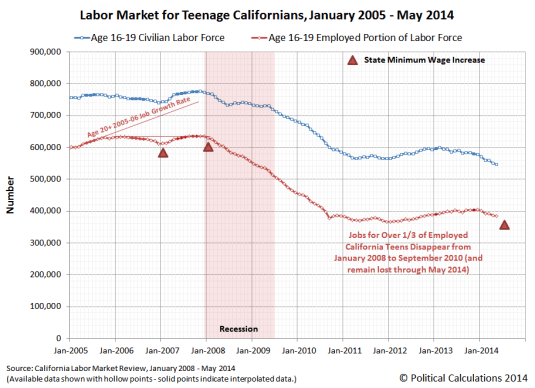

In every episode, except 1996 (which is the smallest hike relative to average wages), there was a distinct decline in the trend of teen employment in the few months before the initial hike until a few months after the follow-up hike. This led Kevin Erdmann to ask:

Is there any other issue where the data conforms so strongly to basic economic intuition, and yet is widely written off as a coincidence?

The other econometrics of the minimum wage in New Zealand

08 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage Tags: difference principle, John Rawls, minimum wage, Pareto improvement, utilitarianism

Auckland University of Technology Associate Professor Gail Pacheco is not quoted as often she should be in the politics of the minimum wage in New Zealand. Her research repeatedly finds that the increases in the minimum wage over the last 10 to 15 years in New Zealand reduced employment, increased unemployment, and reduced skill acquisition among teenagers:

Auckland University of Technology Associate Professor Gail Pacheco is not quoted as often she should be in the politics of the minimum wage in New Zealand. Her research repeatedly finds that the increases in the minimum wage over the last 10 to 15 years in New Zealand reduced employment, increased unemployment, and reduced skill acquisition among teenagers:

- Tim Maloney and Gail Pacheco (2012) found that the real minimum wages increased by nearly 33% for adults and 123% for teenagers in New Zealand between 1999 and 2008. Where fewer than 2% of workers were being paid a minimum wage in 1999, more than 8% of adult workers and 60% of teenage workers are receiving hourly earnings close to the minimum wage. They estimated that a 10% increase in minimum wages, even without any offsetting reduction in earnings due to a loss in employment or hours of work, would lower the relative poverty rate by less than one-tenth of a percentage point!

- Gail Pacheco (2011) review the impact of rising minimum wages on employment in New Zealand over the time period 1986–2004. She found significant negative employment effects of a higher minimum wage.

- Pacheco and Cruickshank (2007) found the youth minimum wage increases resulted in some age groups undergoing a 91% rise in their real minimum wage over the last 10 years. They found that for 16–19 year olds, minimum wage rises have a statistically significant negative effect on educational enrollment levels. But the introduction of the minimum wage appears to have had a significantly positive impact on teenagers’ enrollment levels. This is a possible indication of the ineffective level the minimum wage was set at, in terms of reservation wages of youth in New Zealand.

- Gail Pacheco & Vic Naiker (2006) reviewed the consequences of where in March 2001, the eligibility for adult minimum wage rates was lowered from 20 to 18 years while the youth minimum wage for 16–17 year olds was also increased from 60 to 70% of the adult minimum wage. Most minimum wage workers in New Zealand work in the four sectors: (1) Retail, (2) Textile and apparel, (3) Accommodation, cafes and restaurants, and (4) Agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Using an event study methodology we examine the economic impact of the substantial increase in youth minimum wage rates on employers in industries with high concentrations of minimum wage workers. All conclusions point to there being an insignificant impact on profit expectations for low wage employers by investors.

In summary, increases in the youth minimum wage in New Zealand reduced employment, increased unemployment but did not reduce the profits of employers.

If the minimum wage is operating off the monopsony power of employers, investors should have anticipated that the profits of these employers will fall, but they did not. Investors anticipated that most of the consequences of the minimum wage increases would fall upon low paid workers themselves in terms of loss of employment, greater intensity of work effort and reduce training opportunities.

The minimum wage is an inefficient way of tackling poverty because many minimum-wage earners are actually teenagers or second earners in wealthy households in New Zealand and in all other countries that have a minimum wage. As soon as one person is unemployed as a result of the minimum wage increase or otherwise disadvantaged, applied welfare economics comes into play with concepts like Pareto improvement. How do you trade-off the losses for one with another’s gains.

Most are those who support the minimum wage shift gears their applied welfare economics in all other social context to emphasise how the losers should be given priority and greater weight when adding up the social gains and social losses of economic change.

The social cost of the minimum wage is not discussed in this way: how many jobs are lost and that these job losses are much more important than any gains to society. All that is done is the number of jobs lost is compared with some other social metrics such as how much the wages go up for those that still have a job and that is enough to conclude that there is a socially beneficial change from a minimum wage increase.

Any low paid workers affected by the minimum wage increase are just reduced to numbers and added and subtracted with great ease and few moral compunctions about interpersonal comparisons of utility

A minimum wage increase is not free if one worker loses their job. The Paretian Criterion states that welfare is said to increase or decrease if at least one person is made better off or worse off with no change in the positions of others.

As Rawls pointed out, a general problem that throws utilitarianism into question is some people’s interests, or even lives, can be sacrificed if doing so will maximize total satisfaction. As Rawls says:

[ utilitarianism] adopt[s] for society as a whole the principle of choice for one man… there is a sense in which classical utilitarianism fails to take seriously the distinction between persons.

Minimum wage advocates fail to take seriously that low paid workers who lose their jobs because of minimum wage increases are real living people who suffer when their interests are traded off for the greater good of their fellow low paid workers, some of whom come from much wealthier households.

If the Left want to improve the lot of the poor, they would be doing better by either promoting an institutional framework that promotes general wage growth and by simply increasing the earned income tax credit.

Milton Friedman – A Conversation On Minimum Wage

07 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage, Public Choice Tags: Free to Choose, Milton Friedman, minimum wage

Milton Friedman on raising the minimum wage – the most ‘anti-black law in the land’

01 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, labour economics, minimum wage, Public Choice Tags: Milton Friedman, minimum wage

The minimum wage law is most properly described as a law saying that employers must discriminate against people who have low skills. That’s what the law says.

The law says that here’s a man who has a skill that would justify a wage of $5 or $6 per hour (adjusted for today), but you may not employ him, it’s illegal, because if you employ him you must pay him $9 per hour.

So what’s the result? To employ him at $9 per hour is to engage in charity. There’s nothing wrong with charity. But most employers are not in the position to engage in that kind of charity.

Thus, the consequences of minimum wage laws have been almost wholly bad. We have increased unemployment and increased poverty.

How to refute the case for a minimum wage when genuinely calling for a smarter federal minimum wage

30 Jun 2014 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: federalism, george stigler, minimum wage, monopsony

What if minimum wage rates could somehow be tied to specific locations as suggested by former White House economist Jared Bernstein puts it in an essay in the New York Times:

When we adjust a national minimum wage of $10.10 for regional differences, these are the amounts you’d need to have the same buying power: $11.94 in Washington, D.C., and $11.40 in California, but only $8.90 in Alabama and $9.08 in Kansas.

And of course, prices vary within states as well. In the New York City area, it would take $12.34 to meet the national buying power of $10.10; upstate around Buffalo, you’d need only $9.47. In the Los Angeles area, it would take $11.94; go up north a bit to Bakersfield, where prices are closer to the national average, and it’s $9.83.

To repeat what George Stigler said on the unsuitability of a nation-wide minimum wage in 1946 when there was monopsony, and therefore a small minimum wage increase is less likely to result in a reduction in employment:

If an employer has a significant degree of control over the wage rate he pays for a given quality of labour, a skilfully-set minimum wage may increase his employment and wage rate and, because the wage is brought closer to the value of the marginal product, at the same time increase aggregate output…

This arithmetic is quite valid but it is not very relevant to the question of a national minimum wage. The minimum wage which achieves these desirable ends has several requisites:

1. It must be chosen correctly… the optimum minimum wage can be set only if the demand and supply schedules are known over a considerable range…

2. The optimum wage varies with occupation (and, within an occupation, with the quality of worker).

3. The optimum wage varies among firms (and plants).

4. The optimum wage varies, often rapidly, through time.

A uniform national minimum wage, infrequently changed, is wholly unsuited to these diversities of conditions

A smarter federal minimum wage is a federal minimum wage of zero. Let each state and city set a minimum wage in accordance with its own economic conditions and the blackboard economics of monopsony and competition in the labour market.

As soon as you concede that there is not one single national labour market, other concessions must be made. This slippery slope includes that the monopsony power of employers might vary from state to state, city to city, and local labour market from local labour market.

Even a state or city minimum wage regulator would have to pretend to know an immense amount of information about the labour market with most of this information in a tacit form that cannot be summarised in statistics or other decision aids for regulators. As Hayek reminded in his classic in 1945 on The Use of Knowledge in Society:

the fact that the sort of knowledge with which I have been concerned is knowledge of the kind which by its nature cannot enter into statistics and therefore cannot be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form.

The statistics which such a central authority would have to use would have to be arrived at precisely by abstracting from minor differences between the things, by lumping together, as resources of one kind, items which differ as regards location, quality, and other particulars, in a way which may be very significant for the specific decision.

It follows from this that central planning based on statistical information by its nature cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place and that the central planner will have to find some way or other in which the decisions depending on them can be left to the "man on the spot."

Minimum wage coverage in Europe

24 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in economics, labour economics, minimum wage, unions Tags: median voter, minimum wage, unions

Germany, Denmark, Italy, Austria, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland do not have a statutory minimum wage. Capitalist hell-holes all.

A common feature of this group of countries is the high coverage rate of union agreed minimum wages, generally laid down in sectoral agreements by employers associations with unions.

The percentage of employees covered by union agreed minimum wages ranges from approximately 70% in Germany and Norway to almost 100% in Austria and Italy (though excluding irregular workers, who make up a relatively large share of the Italian labour market). Italy has a huge underground economy.

In Denmark, the percentage of employees covered by union agreed wages is estimated at between 81% and 90%, while in Finland and Sweden, this figure is 90%.

Scandinavia is a capitalist hell-hole that every true blue social democrat must denounce without reservation. Their so called left-wing parties as traitors to the working class and to the least powerful of all workers – the low-paid and unskilled.

The poor should not have to rely on scraps from the tables of the middle-class unions. They have been deserted by their so called social democratic governments.

Whether the low-paid and low-skilled get a fair consideration from unions in collective bargaining given these unions will be driven by majority rule – by the median voter/union member who is older, senior and of high job tenure – is a question worth exploring.

The evidence is not good. In the Finnish depression in the early 1990s, the unions refused to agree to nominal wage cuts despite 20% unemployment – the worst since the 1930s. They protect those that still had a job.

Most European labour markets are dual labour markets. Unions and employment protection laws ensure that they are made up of two-tier systems with ultra-secure permanent jobs with the rest on temporary contracts.

Deirdre McCloskey on the minimum wage

20 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage Tags: Deirdre McCloskey, minimum wage

“Jobs” are deals between workers and employers, and so “creating” them out of unwilling parties is impossible. The state, though, can outlaw deals, and has.

So: eliminate the minimum wage for people younger than 25. The resulting boom in jobs for young people will amaze.

Maybe it will inspire voters to get the state out of the job-outlawing business. Probably not, so sure are we that the state “protects” by stopping deals between willing parties.

What exact did David Card say about the minimum wage?

22 May 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage Tags: David Card, minimum wage

Our findings suggest that the efficiency aspects of a modest rise in the minimum wage are overstated….

[W]e find no evidence for a large negative employment effect of higher minimum wages. Even in the earlier literature, however, the magnitude of the predicted employment losses from a much higher minimum wage would be small: the evidence at hand is relevant only for a moderate range of minimum wages, such as those that prevailed in the U.S. labour market during the past few decades.

Within this range, however, there is little reason to believe that increases in the minimum wage will generate large employment losses.

David Card and Alan B. Krueger, Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995, p. 393).

Recent Comments