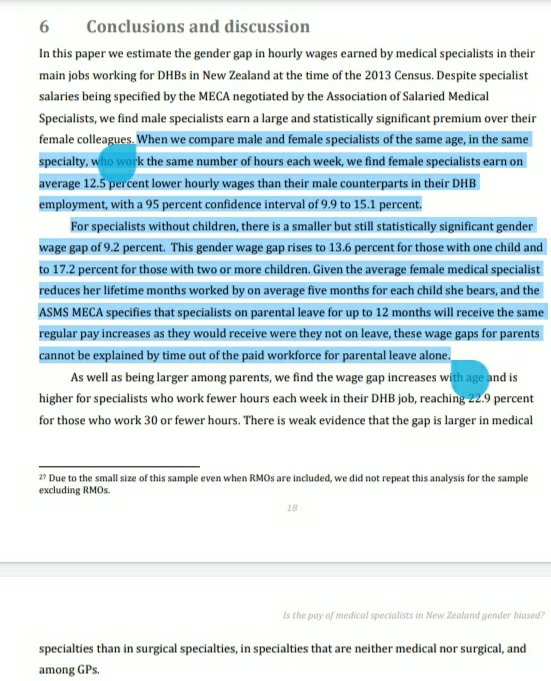

How do DHBs find out how many kids specialists have to pay mothers less per kid? Illegal to ask. Maybe supply-side factors are driving the gender wage gap?

02 Oct 2020 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, econometerics, economics of bureaucracy, economics of education, gender, health economics, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, occupational choice, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice Tags: gender wage gap, motherhood penalty

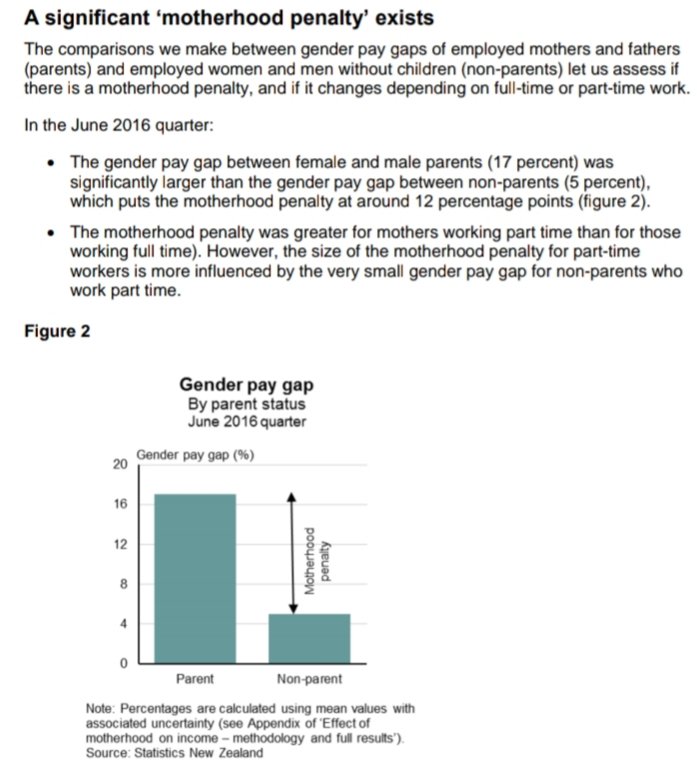

Gender wage gap is bugger all after adjusting for motherhood penalty @women_nz @JulieAnneGenter

25 Oct 2019 Leave a comment

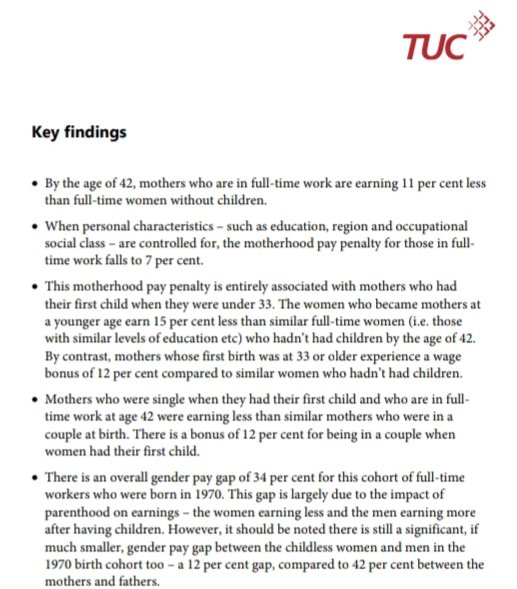

Trade Union Congress nearly summarise the gender wage gap for @women_nz @JulieAnneGenter from a longitudinal study

16 Oct 2019 Leave a comment

@women_nz explains why the gender wage gap has nothing to do with employer discrimination @JulieAnneGenter @JanLogie

18 Sep 2019 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of education, economics of information, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: gender wage gap, motherhood penalty

A sudden spike in employer discrimination or the motherhood penalty

21 Nov 2018 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality Tags: gender wage gap, motherhood penalty

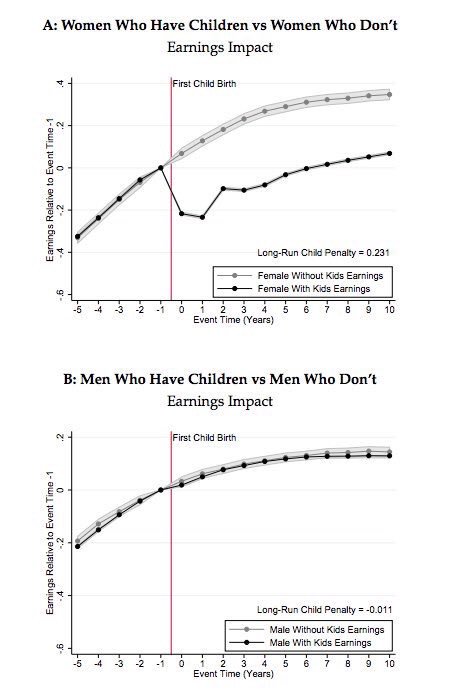

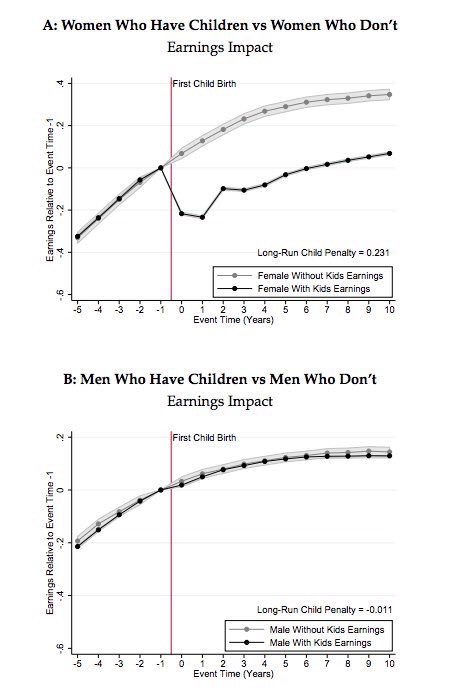

The gender gap in income is primarily driven by motherhood in three countries

30 May 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics Tags: gender wage gap, motherhood penalty

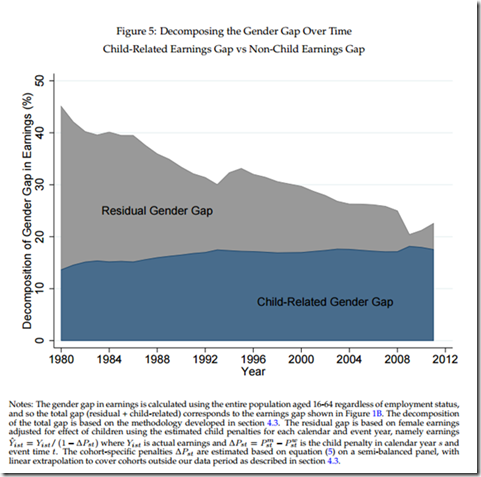

Motherhood explains 80% of the gender wage gap, up from 30% 30 years ago

16 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, economics of families, gender wage gap, motherhood penalty

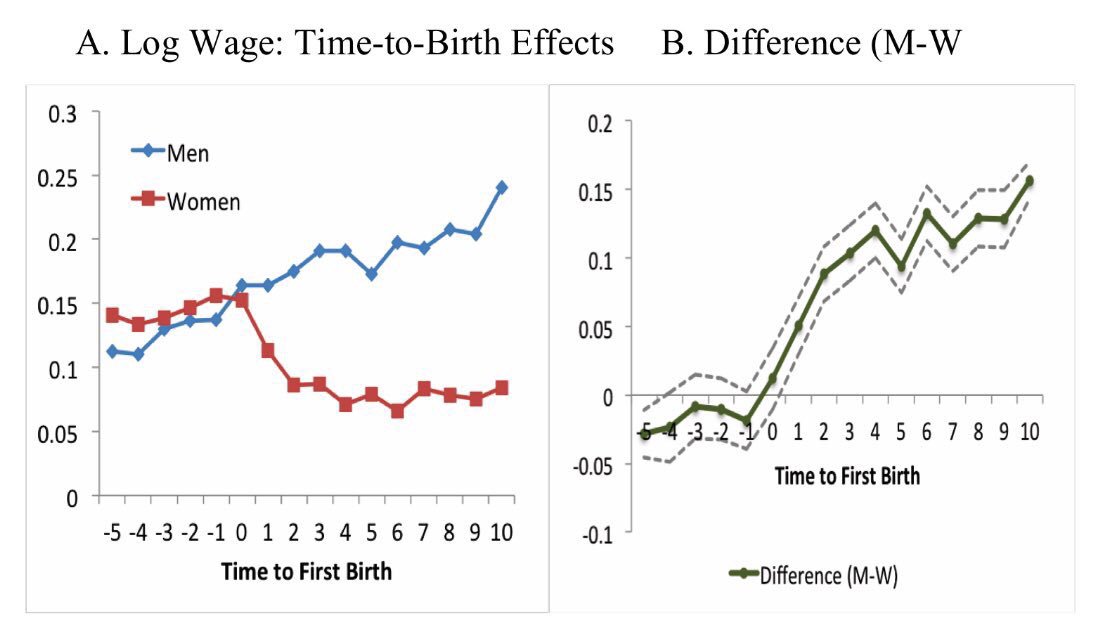

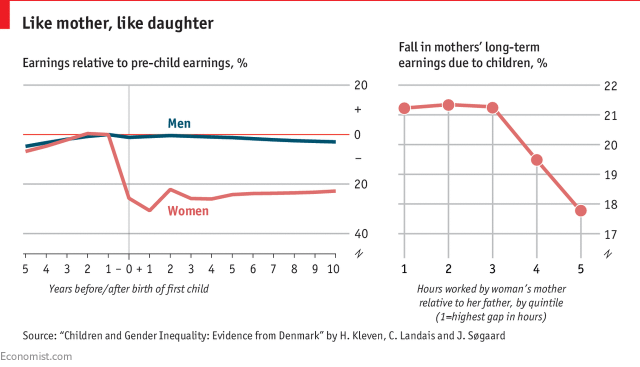

#Women's earnings drop 20% after 1st child & gap remains the same even 20 years later @LSEEcon bit.ly/1M60KfJ http://t.co/UpoqLkhbl2—

STICERD (@STICERD_LSE) July 15, 2015

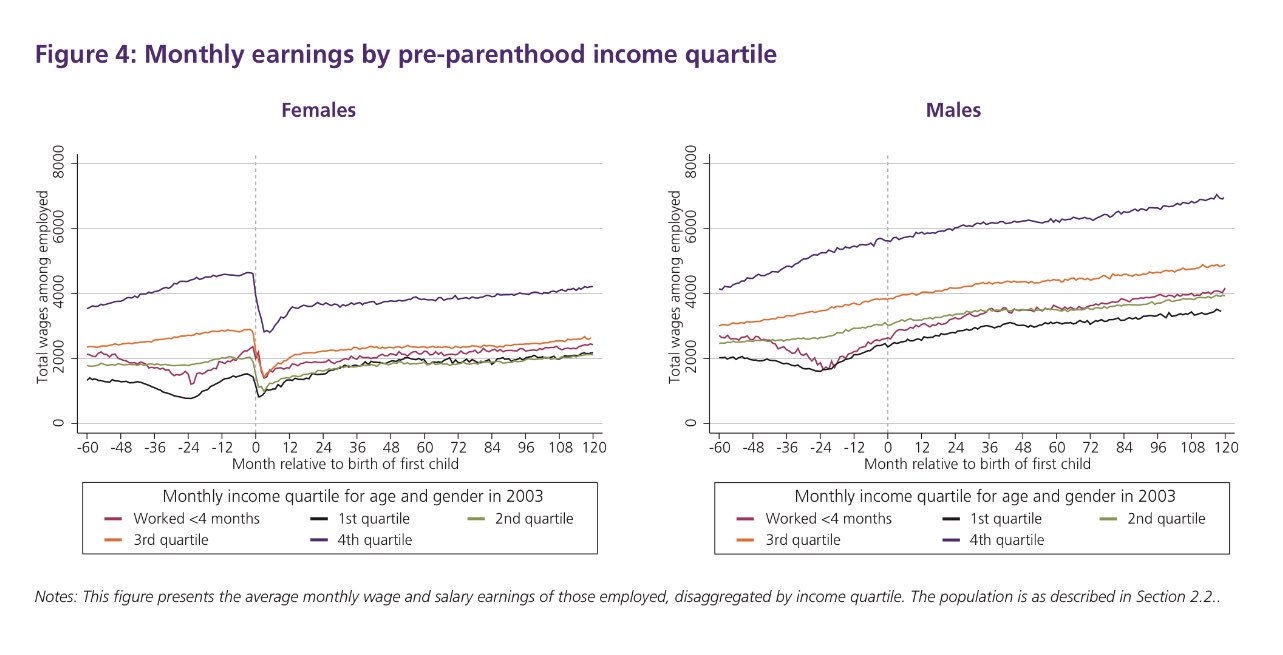

Source: Parenthood and the Gender Gap: Evidence from Denmark by Henrik Jacobsen Kleven, Camille Landais and Jakob Egholt Søgaard, University of Copenhagen January 2015 at http://eml.berkeley.edu/~webfac/auerbach/Landais2015.pdf

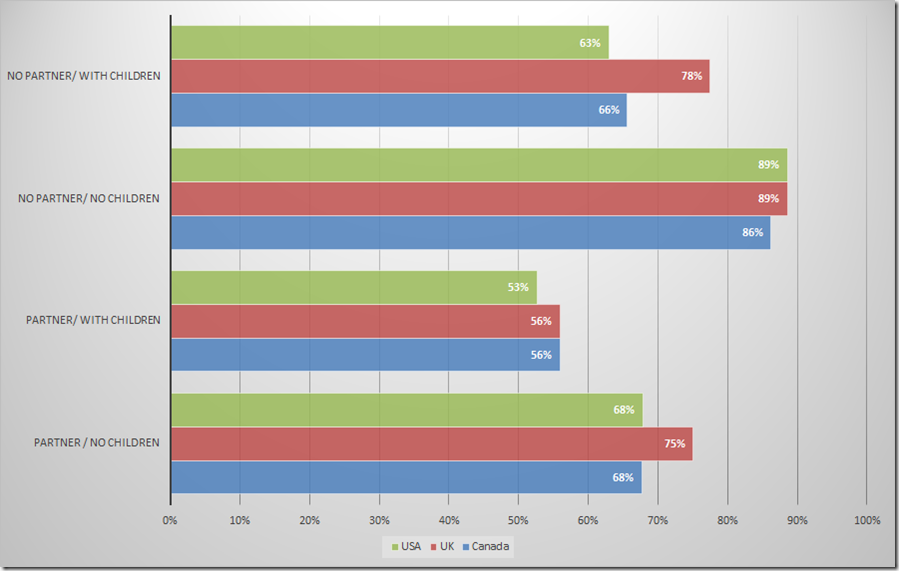

Females/male earnings ratio by partner status and motherhood – USA, UK, Canada

12 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, occupational choice, politics - USA, poverty and inequality Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, British economy, Canada, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce, motherhood penalty

Figure 1: Female/male earnings ratio by partner status and motherhood, 2004  Source: LIS Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg – Wave VI; individuals with positive earnings only. .

Source: LIS Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg – Wave VI; individuals with positive earnings only. .

The gender pay gap and motherhood

06 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender pay gap, motherhood penalty

The division of labour between modern parents

10 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply Tags: engines of liberation, female labour force participation, household production, motherhood penalty

Notice that mothers spent about 30 hours per week on housework in the 1960s. The engines of liberation were smaller families and the availability of a large number of labour saving household white goods, and preprepared and takeaway food.

Women graduates increasingly put their partner’s career first after they graduate | Daily Mail Online

19 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, Claudia Goldin, gender wage gap, motherhood penalty, power couples

Women are increasingly putting their husband’s career before their own, a controversial new study of Harvard Business School graduates has found.

It canvassed over 25,000 male and female students, and found 40 percent of Gen X and boomer women said their spouses’ careers took priority over theirs.

The researchers also said only about 20 percent of them had planned on their careers taking a back seat when they graduated.

This gender gap found by Robin Ely, Colleen Ammerman and Pamela Stone can be better explained by the marriage market combined with assortative mating.

1. Harvard business graduates are likely to marry each other and form power couples.

2. There tends to be an age gap between men and women in long-term relationships and marriages of say two years.

This two year age gap means that the husband as two additional years of work experience and career advancement. This is highly likely to translate into higher pay and more immediate promotional prospects.

Maximising household income would imply that the member of the household with a higher income, and greater immediate promotional prospects stay in the workforce.

It is entirely possible that women to anticipate this situation both in their subject choices and career ambitions.

Claudia Goldin found that the wage gap between male and female Harvard graduates disappears in the presence of one confounding factor.

That confounding factor is obvious: the male in the relationship earns less. When this is so, Goldin found that the female in the relationship earns pretty much as do similar male Harvard graduates, except for the fact that they work less hours per week:

We identify three proximate factors that can explain the large and rising gender gap in earnings: a modest male advantage in training prior to MBA graduation combined with rising labour market returns to such training with post-MBA experience; gender differences in career interruptions combined with large earnings losses associated with any career interruption (of six or more months); and growing gender differences in weekly hours worked with years since MBA.

Differential changes by sex in labour market activity in the period surrounding a first birth play a key role in this process. The presence of children is associated with less accumulated job experience, more career interruptions, shorter work hours, and substantial earnings declines for female but not for male MBAs.

The one exception is that an adverse impact of children on employment and earnings is not found for female MBAs with lower-earning husbands.

This sociological evidence reported in the Daily Mail is entirely consistent with the choice hypothesis and equalising differentials as the explanation for the gender wage gap. As Solomon Polachek explains:

At least in the past, getting married and having children meant one thing for men and another thing for women. Because women typically bear the brunt of child-rearing, married men with children work more over their lives than married women.

This division of labour is exacerbated by the extent to which married women are, on average, younger and less educated than their husbands.

This pattern of earnings behaviour and human capital and career investment will persist until women start pairing off with men who are the same age or younger than them.

The day that sex discrimination died – Solomon Polachek on the gender wage gap

04 Nov 2014 1 Comment

in discrimination, gender, human capital, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, Gary Becker, gender wage gap, habits and traditions, human capital, labour economics, motherhood penalty, sex discrimination, Solomon Polachek

Solomon Polachek was minding his own business back in 1975 looking for evidence to show occupational crowding and that women were pushed into low paid occupations by sex discrimination, and in particular, employer discrimination. About 60 per cent of women still work in just 10 occupations. the occupations which are female-dominated are often relatively poorly paid jobs

By chance, Polachek departed from the usual empirical strategy for estimating the male-female wage gap at that time.

Rather than include a dummy variable to estimate discrimination after various factors have been taken into account, he introduced dummy variables that took account of both gender and marital status. His results were startling.

He previously was able to explain about 35% of the wage gap using the data at hand and variables he was using.

This 35% gap dropped to 18% for single never married males and females, but his ability to explain the gender wage gap increased dramatically to over 60% for married spouse present males and females.

What more, the presence of children exacerbated the gender wage gap. Each child of less than 12 years old widened the female male pay disparity by 10%. Furthermore, large spacing intervals between children widened this gender wage disparity even further.

Subsequent research showed that marital status had the same effects on gender wage gaps in Germany, the UK, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway and Australia. Factors associated with dropping out of the labour market to care for children could explain up to 93% of the gender wage gap.

These findings are devastating to the notion that there is some sort of discrimination against women on the demand side of the labour market. As Polachek explains:

The gender wage gap for never marrieds is a mere 2.8%, compared with over 20% for marrieds. The gender wage gap for young workers is less than 5%, but about 25% for 55–64-year-old men and women.

If gender discrimination were the issue, one would need to explain why businesses pay single men and single women comparable salaries. The same applies to young men and young women.

One would need to explain why businesses discriminate against older women, but not against younger women. If corporations discriminate by gender, why are these employers paying any groups of men and women roughly equal pay?

Why is there no discrimination against young single women, but large amounts of discrimination against older married women?

… Each type of possible discrimination is inconsistent with negligible wage differences among single and younger employees compared with the large gap among married men and women (especially those with children, and even more so for those who space children widely apart).

The main drivers of the gender wage gap is simply unknown to employers such as whether the would-be recruit or employer is married, their partner is present, how many children they have, how many of these children are under 12, and how many years are there between the births of their children. These are the main drivers of the gender wage gap – all of which are factors totally unknown to employers and of no relevance to them in making a profit.

The drivers of the gender wage gap on the supply side of the labour market regarding the choices women make about having children, when they have children, and how this influences their investment in human capital, and in particular, in human capital that does not depreciate by that much because of intermittent labour force participation due to motherhood.

Occupational crowding hypotheses of the gender wage gap have the drawback of being an invisible hand explanation of social outcomes. Each individual, acting only to best secure her own rights and interests, act in such a way that the unintended outcome of a complex social interaction.

The specific unintended outcome that must arise from millions of choices of people acting in their own interest throughout their lives is occupational segregation.

The market process of the invisible hand has both a filter and and equilibrating mechanism. The filter is profits and loss to exclude through insolvency and bankruptcy those entrepreneurial choices that do not further consumer’s interests. The equilibrating mechanism – the mechanism that tells people which choices they should make – is price signals. Price signals guide individual choices towards the unintended outcome.

Those that argue that women are socialised to make particular choices such as mother were not paying attention to the 20th century and the radical social change over the course of that century, in particular in the role of women. As Gary Becker explains:

… major economic and technological changes frequently trump culture in the sense that they induce enormous changes not only in behaviour but also in beliefs.

A clear illustration of this is the huge effects of technological change and economic development on behaviour and beliefs regarding many aspects of the family.

Attitudes and behaviour regarding family size, marriage and divorce, care of elderly parents, premarital sex, men and women living together and having children without being married, and gays and lesbians have all undergone profound changes during the past 50 years.

Invariably, when countries with very different cultures experienced significant economic growth, women’s education increased greatly, and the number of children in a typical family plummeted from three or more to often much less than two.

Recent Comments