Personal cameras as evidence that criminal deterrence works and works well

16 Jul 2015 1 Comment

in economics of crime, law and economics, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: body cameras, crime and punishment, criminal deterrence, police, prisons

Hutt City Council parking wardens are the latest in a long line of frontline staff to wear lapel cameras to deter assaults and verbal abuse. These lapel cameras are another illustration about how criminals and miscreants respond to incentives and are deterred by a greater prospect of being caught, convicted and punished. In the case of lapel cameras, there is a greater prospect of been identified and recorded for later proceedings.

The introduction of personal cameras in New Zealand prisons in high risk areas lead to a large reduction in the number of incidents of violence and abuse towards prison staff. Chief custodial officer Neil Beales said:

The use of on body cameras has led to a 15 to 20 per cent reduction in disruptive incidents (which can range from very minor to more serious) in units where cameras were used, compared with units where they were not used.

Even hardened prison inmates respond to incentives and a greater prospect of being caught and punished.

The introduction of personal cameras is not a priority for the New Zealand police. Mention was made of a six year long budget freeze as one of the reasons.

The first randomized controlled trial of police body cameras in the USA showed that cameras sharply reduce the use of force by police and the number of citizen complaints.

In Seattle, where a dozen officers started wearing body cameras in a pilot program in December, the police department has set up its own YouTube channel, broadcasting a stream of blurred images to protect privacy.

Security cameras in prison showers and the case for private prisons

06 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of crime, entrepreneurship, law and economics, organisational economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: do gooders, law and order, prisons

I was listening to a radio show the other day on the introduction of close circuit television into New Zealand prisons that were to be monitored by both male and female guards. This is regarded as an indignity by some because these new close circuit cameras would be in showers and toilets.

The initial commentators on the radio programme immediately said they had watched plenty of TV programs where people were shanked in the showers.

The close circuit television was for the safety of prisoners. Close circuit cameras in all parts of prisons made prisons a safer place and that was that. It was the price of safety, especially for prisoners vulnerable to intimidation and sexual assault.

Greg Newbold, a New Zealand criminologist and an ex-prisoner in itself, then came on air to criticise the introduction of close circuit televisions in showers and other intimate areas such as toilets as an indignity on prisoners. Prisoners have a right to intimate privacy in his view. He said only 12 prisoners had been murdered in the New Zealand prisons since 1979.

Only 12 murders is 12 murders too many. Every one of those murders would have been subject of outrage about the failure of the prison administration from the bleeding hearts brigade.

The most interesting thing that Greg Newbold said on the radio was about how these close circuit television systems first emerged in prisons, initially in the USA.

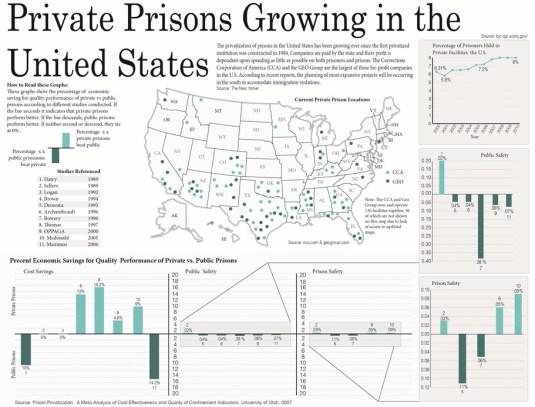

Close circuit television systems will put throughout prisons initially in private prisons to avoid being sued for wrongful death and injury. The private prisons introduced this rather obvious security measure to reduce liability in the civil courts.

Public prisons are supposedly a safer place for prisoners to be if you listen to the bleeding hearts brigade and the Left over Left. Pubic prisons but never got around introducing what seems to me to be a rather basic security measure in confined areas of prisons. Close circuit television systems would protect both inmates and guards.

The different incentives facing public and hybrid prisons, in this case, exposure to litigation, is an illustration of the superior efficiency of private prisons.

Private prisons did something because it affects the bottom line. One way to reduce liability for deaths and injuries is prison security measures that reduce the number of deaths and injuries in prisons.

More importantly, private prisons have unforgiving critics in the form of the bleeding hearts brigade and Left over Left. No one on the Left will defend or protect a prison that is private from closure out of a knee-jerk defence of the public sector, and in particular, public-sector unions.

Oddly enough the only prison that the Left over Left want to close in New Zealand is the highest performing prison, Mt Eden, which happens to be privately run.

The main problem with private prisons is contracting over quality where it is difficult to define quality and measure performance against quality standards specified in a contract as Andrew Shleifer explains:

…critics of privatization often argue that private contractors would cut quality in the process of cutting costs because contracts do not adequately guard against this possibility

Privatisation for many government services is simply an extension of the make-or-buy decision. Every firm faces a make-or-buy decision – should the firm buy a production input from outside suppliers or should it make what it needs itself with existing or additional internal resources?

As any industry grows, there is more room for more specialised producers to supply to firms of all sizes at a lower cost than in-house production (Stigler 1951, 1987; Levy 1984). As an example, all with the largest firms intermittently hire legal, accounting and many other professional skills from specialists.

By contracting-out to these more specialised and niche suppliers, firms can enjoy all available economies of scale in production unless its needs are unique or the firm has some special competency in producing the input in-house (Lindsay and Maloney 1996; Shughart 1997; Roberts 2004). Firms in most industries capture all available economies of scale at relatively small sizes after which they have a long region of production where their marginal cost of further increases in production are constant (Stigler 1958; Lucas 1978; Barzel and Kochin 1992; Shughart 1997).

Put simply, an entrepreneur makes what he or she cannot buy at the quality preferred through contracting in market:

The case for in-house provision is generally stronger when non-contractible cost reductions have large deleterious effects on quality, when quality innovations are unimportant, and when corruption in government procurement is a severe problem. In contrast, the case for privatization is stronger when quality reducing cost reductions can be controlled through contract or competition, when quality innovations are important, and when patronage and powerful unions are a severe problem inside the government.

The way in which the market process dealt with chiselling on quality where quality reducing cost reductions where costly to control through contract or competition was the emergence of non-profit institutions. The competitive edge of these non-profit institutions was they had fewer incentives to dilute hard to measure qualities of the product transacted.

Any additional profits from this dilution of quality were not distributed to the owners because the non-profit organisation was either run by a charity or was owned mutually by the customers. The proceeds from cutting corners on quality could not be paid out to the owners in dividends because there were none.

Examples of non-profits competing successfully in the market are obvious, such as life insurance. Until recent decades, most life insurance companies were mutually owned by the policyholders. Life insurance companies were mutually owned as an assurance that no one could run off with the money by paying high dividends to the owners before policyholders died many years after they have paid their premiums.

Most private universities are run as non-profit institutions even when they are set up by private developers with profits in mind. The private university itself is owned by a charity with esteemed persons on the board to assure quality and probity. The active involvement of alumni is encouraged as a further guard of the future quality of the University from which they graduated. The private developers make their profit on the surrounding land as the university grows and prospers. Land grant universities in the USA may have operated this way.

Other examples of the emergence of non-profit institutions to assure quality in a competitive market are private schools, private hospitals, and private day care centres where concerns about the private provision of a quality service arise, with or without justification. Andrew Shleifer again:

…entrepreneurial not-for-profit firms can be more efficient than either the government or the for-profit private suppliers precisely … where soft incentives are desirable, and competitive and reputational mechanisms do not soften the incentives of private suppliers [to dilute quality].

Of course, any proper analysis must compare like with like and compare the dismal record of public prisons date in terms of prisoner and prison guard safety and preventing escapes with any scandals in the private prison systems. Few do that.

Recent Comments