Behind on my vaccination blogging

13 Oct 2020 Leave a comment

in health economics Tags: antivaccination movement, public goods, vaccines

Biggest barrier to a #COVID19 vaccine take-up

11 Aug 2020 Leave a comment

in health economics Tags: economics of pandemics, free-riders, public goods, vaccines

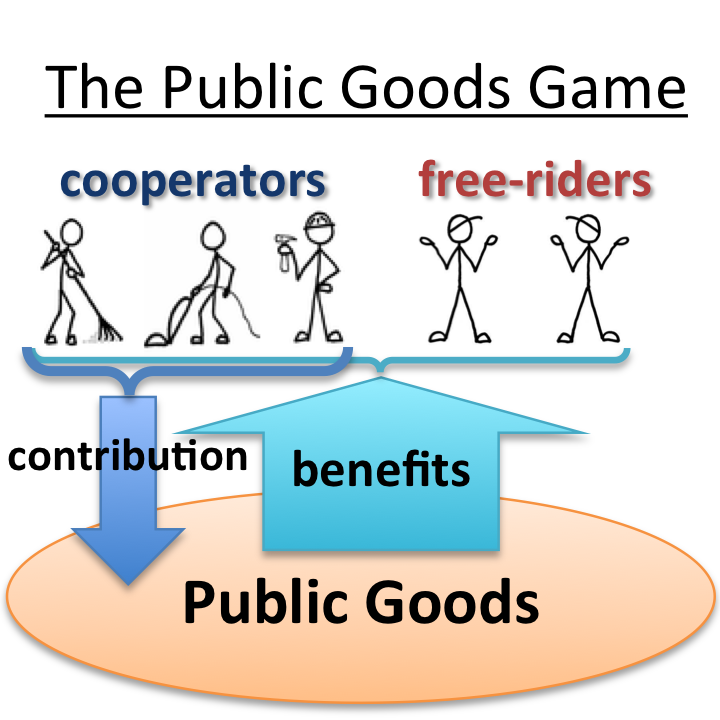

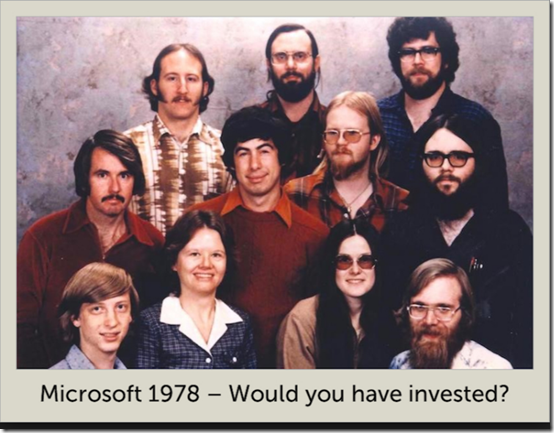

What Is the Free Rider Problem?

27 Dec 2018 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, property rights, Public Choice, public economics Tags: public goods

Economics of California’s AB32 Global Warming Regulation

25 May 2017 Leave a comment

in economics, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking, transport economics, urban economics Tags: carbon tax, carbon trading, club goods, expressive voting, public goods

The Tragedy of the Commons

20 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics of regulation, environmental economics Tags: public goods, tragedy of the commons

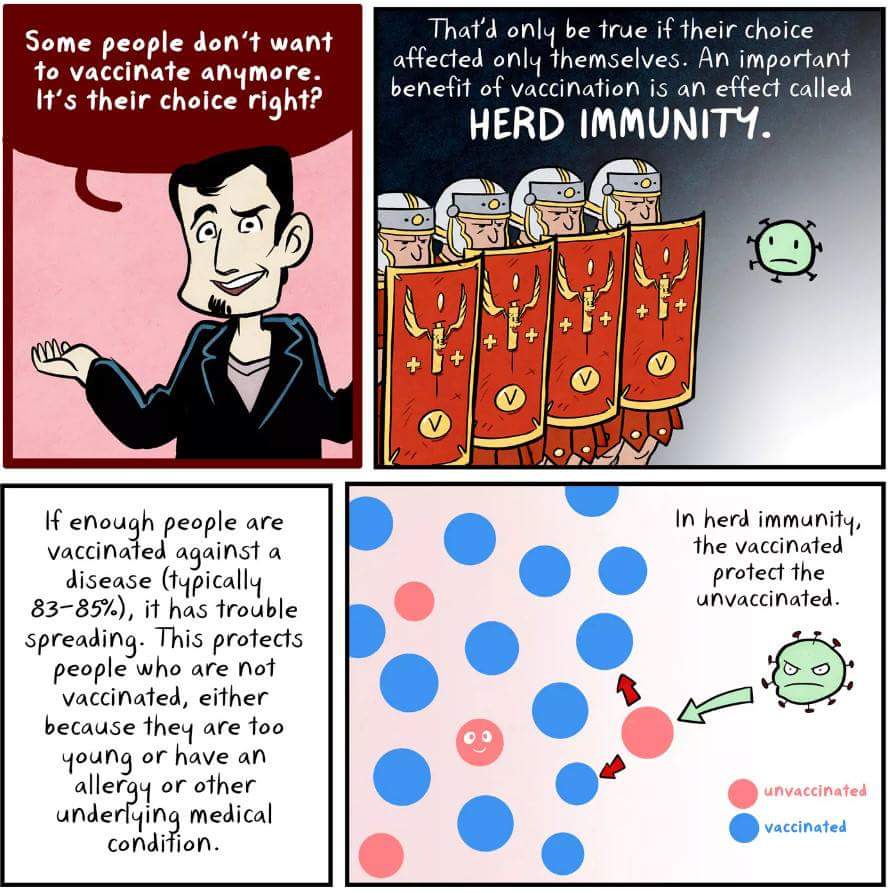

Post-disaster co-operation: The voluntary provision of weakest-shot public goods

16 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of natural disasters, public economics Tags: economics of alliances, free riding, post-disaster cooperation, public goods, weakest shot public goods

After a natural disaster, both the economic and social fabric and the survival of individual employers each become weakest-shot public goods. The provision of these public goods temporarily depend by much more than is usual on the minimum individual contributions made – the weakest shots made for the common good. The supply of most public goods usually is not dependent on the contributions of any one user.

The classic example of a weakest shot public good by that brilliant applied price theorist Jack Hirschleifer is a dyke or a levee wall around a town. It is only as good as the laziest person contributing to its maintenance on their part of the levee. Vicary (1990, p. 376) lists other examples:

Similar examples would be the protection of a military front, taking a convoy across the ocean going at the speed of the slowest ship, or maintaining an attractive village/landscape (one eyesore spoils the view).

Many instances of teamwork involve weak-link elements, for example moving a pile of bricks by hand along a chain or providing a theatrical or orchestral performance (one bad individual effort spoils the whole effect.)

Most doing the duty is essential to the survival of all after a natural disaster. The alliances we call societies and the firm, normally not in danger of collapse, are threatened if there is a natural disaster. In these highly unusual circumstances, alliance-supportive activities, greater cooperativeness and self-sacrifice become an important public good.

In normal periods when threats are small, what social control mechanisms that are in place are sufficient and there is no need for exceptional behaviour and self-sacrifice.

Everyone has an interest in the continuity of the economic and social fabric and the survival of their employers in times of adversity. Individual contributions to these national and local public goods become much more decisive after a natural disaster.

In normal times people behave in a conventionally cooperative way because individually they find it profitable to do so. There is some slippage around the edges and there are social control mechanisms to deter illegal conduct and supply public goods.

As the threat to the social and economic fabric grows after a natural disaster, eventually the social and economic balance may hang by a hair. When this is so, any single person can reason that his own behaviour might be the social alliance’s weakest link. International military and political alliances also rise and fall on this weakest link basis.

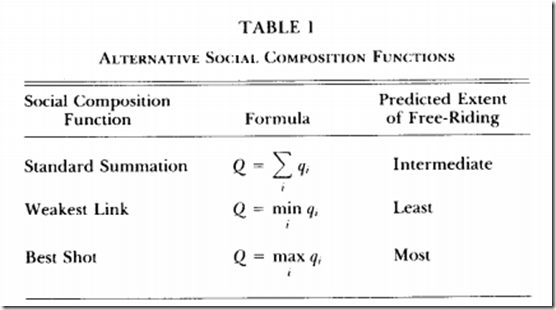

Nitpicking @stevenljoyce reply 2 @TaxpayersUnion on corporate welfare @JordNZ

05 Jul 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economics of bureaucracy, industrial organisation, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking, survivor principle Tags: creative destruction, endogenous growth theory, industry policy, innovation, picking losers, picking winners, public goods, R&D, water economics

The best the Minister for Economic Development, Steven Joyce, could do in response to my recent report on corporate welfare was nit-picking. Joyce said my definition of corporate welfare was flawed and that spending on R&D will grow the economy. He said

“To brand things like tourism promotion and building cycle-ways as corporate welfare is, I think, creative but not accurate at all.”

Joyce also said my report was

just somebody picking out a whole bunch of government programmes that in many cases don’t involve payments to firms at all…

Those that do involve payments to firms are specifically designed to encourage the development for example of the business R&D industry. Politicians don’t choose them.

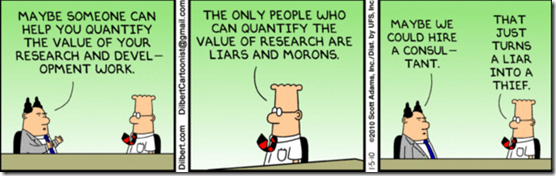

Payments in kind are business subsidies. R&D is so important to the economy that the last thing you want is its direction to be biased by funding from government. Bureaucrats have a conservative bias and do not fund oddballs and long shots. The oddballs and hippies in the picture below could only afford the photo because they won a radio competition in Arizona.

The R&D expenditure that was criticised in my report was commercialisation, not basic research, which was specifically praised. Which research to commercialise is for entrepreneurs.

There is no reason whatsoever to think bureaucrats administering R&D subsidy budgets set by politicians are any better than private entrepreneurs at picking the next big thing.

Page 33 of "An Illustrated Guide to Income" more economic #dataviz at: bit.ly/10M7lqR http://t.co/FcmaqZWB32—

Catherine Mulbrandon (@VisualEcon) May 09, 2013

If bureaucrats were any good at picking winners, were any good at beating the market, they would go work for a hedge fund on an astronomically better salary package. The salary package of one top hedge fund manager exceeds the entire payroll budget of most New Zealand government departments including those administering R&D subsidies and other hand-outs.

Government expenditure in vital areas such as innovation should be justified on the basis of cost-benefit ratios and a rationale for why bureaucrats have superior access to information about the entrepreneurial prospects of unproven technologies and product prototypes.

Subsidies should not be defended because of their popularity and sexiness as Mr Joyce did for the film industry, tourism promotion and ultra-fast broadband

If they told New Zealanders that in their view tourism promotion should be cancelled, the film industry should close down, that their shouldn’t be any ultra-fast broadband…I don’t think people would be that enamoured with it.

On irrigation funding, Mr. Joyce cited a report by NZIER that found irrigation contributes $2.2 billion to the economy. Irrigation is a private good which can funded by pricing it properly including the recovery of capital costs. There is no case for a subsidy.

Public goods have spillovers, private goods such as water and irrigation do not. Users can fund the irrigation themselves buying as little or as much water as they are willing to pay out for out their own pockets. The NZIER report noted that it was not about the case for public funding:

… we are not able to quantify the environmental or social impacts if irrigation had never occurred. We also do not attempt to investigate the relative merits of public versus private sector funding of the schemes.

A Deeper Look at Public Goods

17 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, comparative institutional analysis, public economics Tags: public goods

David Friedman explains incentive incompatibility and comparative institutional analysis

18 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, David Friedman, industrial organisation, law and economics, property rights Tags: incentive incompatibility, public goods

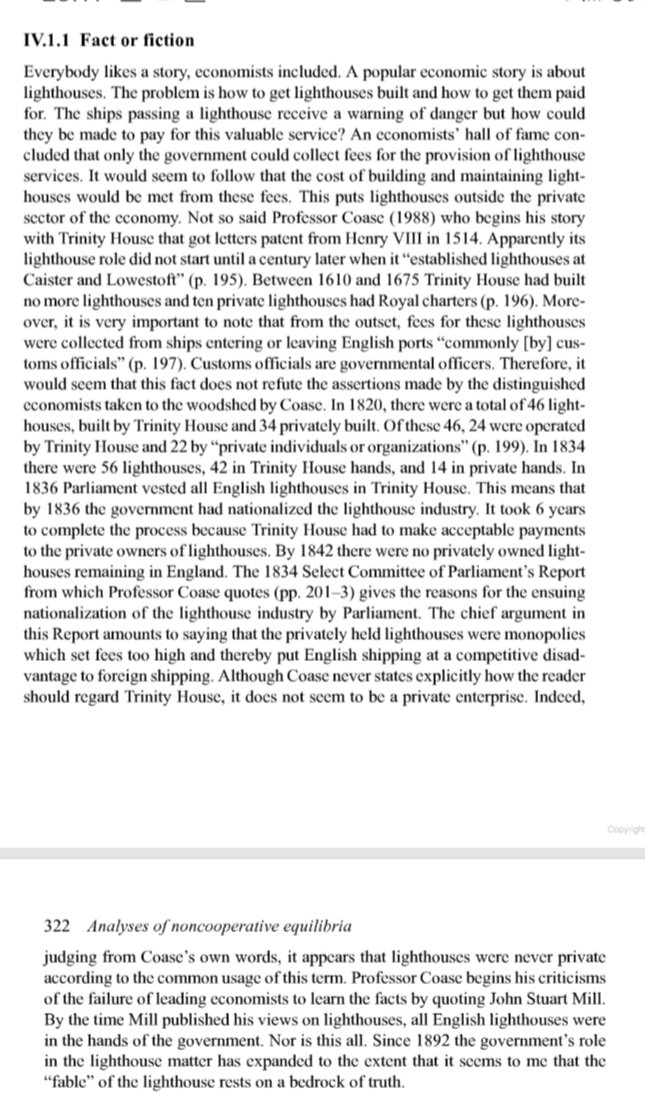

The herd immunity role of #vaccinations explained

16 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, health economics, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: Anti-Science left, anti-vaccination movement, best shot public goods, cheap riders, common law, free-riders, good shot public goods, herd immunity, measles, New Zealand Greens, public goods, quackery, tort law, vaccinations, vaccines

Some public goods can be not provided much at all if even a few do not contribute – free ride. These are called weakest shot public goods. The link in the chain is only as strong as the weakest link for some public goods. The fighting against communicable diseases is an example of that.

The classic example given by that brilliant applied price theorist Jack Hirschleifer is a dyke or a levee wall around a town. It is only as good as the laziest person contributing to its maintenance on their part of the levee wall. Vicary (1990, p. 376) lists other examples:

Similar examples would be the protection of a military front, taking a convoy across the ocean going at the speed of the slowest ship, or maintaining an attractive village/landscape (one eyesore spoils the view).

Many instances of teamwork involve weak-link elements, for example moving a pile of bricks by hand along a chain or providing a theatrical or orchestral performance (one bad individual effort spoils the whole effect.)

Another example of weakest shot public goods is community cooperation after disasters. The quality of the public good provided is equal to the contribution of the weakest person who may start a criminal rampage despite the good efforts of everyone else.

People tend to be more cooperative after natural disasters. They realise their contribution is more important than normal to the maintaining of the social fabric which is currently hanging by a thread.

People tend to be more cooperative after natural disasters. They realise their contribution is more important than normal to the maintaining of the social fabric which is currently hanging by a thread.

Vaccinations are example of a weakest shot public good. The quality of herd immunity depends fundamentally on just about everybody contributing by getting vaccinated. Not all public goods depend on the some of those contributions made. In some cases just a few people choosing to free ride can greatly undermine the public interest.

The reverse of a weakest shot public good is best shot public goods. Example of this is the development of vaccines themselves. The public good is only as good as the best effort at developing the new vaccine with all the others efforts pointless because the best of the vaccines is chosen.

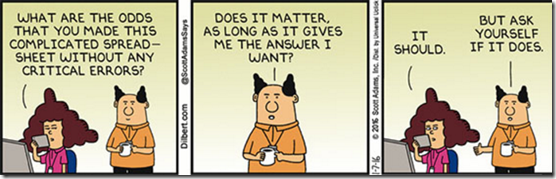

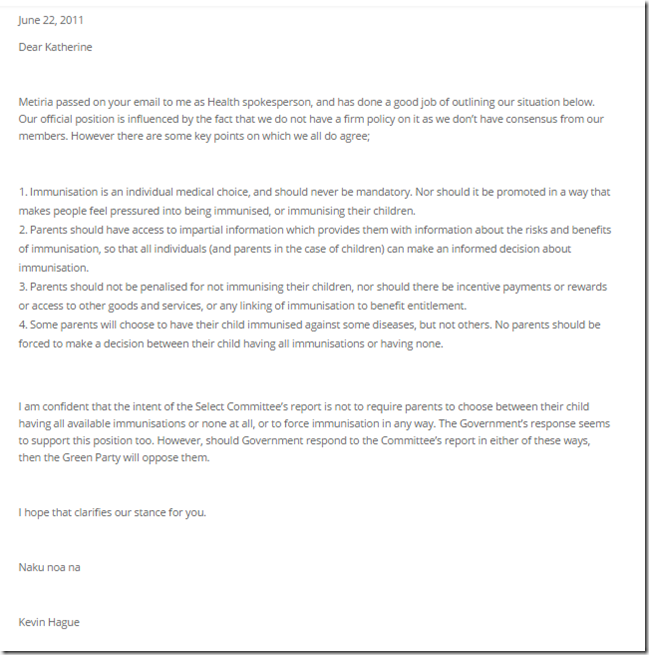

The most curious people in New Zealand to oppose measures to address the under provision of weakest shot public goods are the New Zealand Greens.

https://twitter.com/KevinHague/status/642505850360213505

The Greens are usually the 1st to stress the importance of communities working together for the common good.

https://twitter.com/KevinHague/status/642530277177192448

Herd immunity protects those who cannot be safely vaccinated including new babies, those for whom the vaccine fails, which occasionally happens, and those with compromised immunity such as adults receiving chemotherapy.

Deliriously hot @guardian sim shows why anti-measles jabs help protect your whole community gu.com/p/45f7e/stw http://t.co/H31ZKbXkqg—

Info=Beautiful (@infobeautiful) February 05, 2015

We are all in this together. It is time for the New Zealand Greens to stop pandering to those are only think of themselves and what a free ride on others including the very sick and new babies.

Source: NOVA | What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity requires vaccination rates of about 94%. The near universal vaccination rates required for herd immunity are to smaller margin to pander to an awkward squad who do not want to vaccinate despite the harm they do to others.

Harm to others is grounds and has always been grounds for public policy and public health interventions. Instead, the Greens are anti-science, anti-public health.

Measles is the most contagious disease known to man. Seven children died in New Zealand in the last measles outbreak in 1991. The dead are already too many from the anti-vaccination quacks and cranks.

Recent Comments