Speaking of natural monopolies and predatory entry – Netscape is 20 years old today!

15 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, law and economics Tags: browser wars, law and economics, Microsoft anti-trust trial, Richard McKenzie, Robert Bork, scourge of lower prices, William Shugart

You show your age when you remember that people used to pay $49 to download the Netscape Navigator browser.

Yes,people used to pay for browsers until nasty Microsoft came along in act of predatory entry started giving its Internet browser away from free in the hope of monopolising the market once Netscape went out of business when it would jack its price up again to recoup the intervening losses.

After the first browser war, the usage share of Netscape had fallen from over 90 percent in the mid-1990s to less than one percent by the end of 2006.

During the 1990s, Microsoft competitors — Netscape, IBM, Sun Microsystems, WordPerfect, Oracle, and others —pressed the Justice Department to sue Microsoft for tying Internet Explorer to Windows even though only one of them, Netscape, had a browser.

The demise of Netscape was a central premise of Microsoft’s antitrust trial, where the Court ruled that Microsoft’s bundling of Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system was a monopolistic and illegal business practice.

After losing on appeal , the Department of Justice announced in September 2001 that it was no longer seek to break up Microsoft and would instead seek a lesser antitrust penalty. Microsoft decided to draft a settlement proposal allowing PC manufacturers to adopt non-Microsoft software.

As William Shughart and Richard McKenzie observed:

Microsoft’s critics have advanced a number of economic theories to explain why the firm’s behaviour has violated the antitrust laws.

None of those critics has articulated why or how consumers have been harmed in the process.

Instead, the furious attacks on Microsoft have focused on the injuries supposedly suffered by rivals (on account of Microsoft’s pricing and product-development strategies) and by computer manufacturers and Internet service providers (on account of Microsoft’s “exclusionary contracts”).

Before former Judge Robert Bork became a lobbyist for Microsoft’s rivals, he said in The Antitrust Paradox:

Modern antitrust has so decayed that the policy is no longer intellectually respectable.

Some of it is not respectable as law; more of it is not respectable as economics; and … because it pretends to one objective while frequently accomplishing its opposite … a great deal of antitrust is not even respectable as politics.

A simple rule for a complex world: the moment that evidence is tended to a court about what happened to the competitors in a lawsuit under competition law, that court must dismiss the suit out of hand.

Too many lawsuits under competition law are designed to protect the consumer from the scourge of lower prices!

The best proof that a merger or other business practice is pro-consumer is the rival firms in that market are against it. Why would a firm be against a merger or other business practice that raises the prices of their business rivals?

HT: HistoricalPics

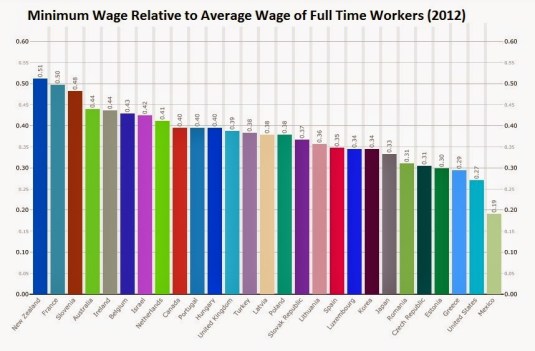

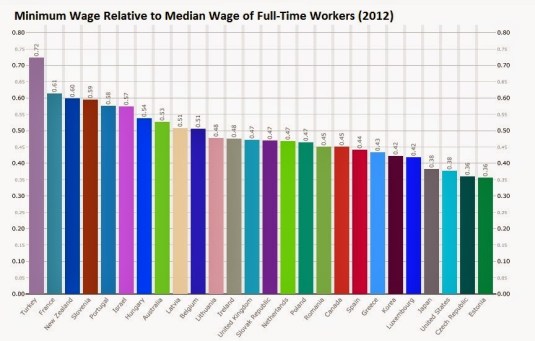

New Zealand has the highest minimum wage in the world

19 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage, Uncategorized Tags: minimum wage, offsetting behaviour, Richard McKenzie, unintended consequences

John Schmitt lists 11 margins along which a minimum wage might cause changes:

- Reduction in hours worked (because firms faced with a higher minimum wage trim back on the hours they want)

- Reduction in non-wage benefits (to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage)

- Reduction in money spent on training (again, to offset the higher costs of the minimum wage)

- Change in composition of the workforce (that is, hiring additional workers with middle or higher skill levels, and fewer of those minimum wage workers with lower skill levels)

- Higher prices (passing the cost of the higher minimum wage on to consumers)

- Improvements in efficient use of labour (in a model where employers are not always at the peak level of efficiency, a higher cost of labour might give them a push to be more efficient)

- “Efficiency wage” responses from workers (when workers are paid more, they have a greater incentive to keep their jobs, and thus may work harder and shirk less)

- Wage compression (minimum wage workers get more, but those above them on the wage scale may not get as much as they otherwise would)

- Reduction in profits (higher costs of minimum wage workers reduces profits)

- Increase in demand (a higher minimum wage boosts buying power in overall economy)

- Reduced turnover (a higher minimum wage makes a stronger bond between employer and workers, and gives employers more reason to train and hold on to workers)

Richard McKenzie argues that the biggest impact of a minimum wage increase is reductions to paid and unpaid benefits for minimum wage workers, including health insurance, store discounts, free food, flexible scheduling, and job security resulting from higher-skilled workers drawn to the higher minimum wage jobs:

- Masanori Hashimot found that under the 1967 minimum-wage hike, workers gained 32 cents in money income but lost 41 cents per hour in training—a net loss of 9 cents an hour in full-income compensation. Several other researchers in independently completed studies found more evidence that a hike in the minimum wage undercuts on-the-job training and undermines covered workers’ long-term income growth.

- Walter Wessels found that the minimum wage caused retail establishments in New York to increase work demands by cutting back on the number of workers and giving workers fewer hours to do the same work.

- Belton Fleisher, L. F. Dunn, and William Alpert found that minimum-wage increases lead to large reductions in fringe benefits and to worsening working conditions.

- Mindy Marks found that workers covered by the federal minimum-wage law were also more likely to work part time, given that part-time workers can be excluded from employer-provided health insurance plans.

McKenzie also argued that if the minimum wage does not cause employers to make substantial reductions in fringe benefits and increases in work demands, then an increased minimum should cause

(1) an increase in the labour-force-participation rates of covered workers (because workers would be moving up their supply of labour curves),

(2) a reduction in the rate at which covered workers quit their jobs (because their jobs would then be more attractive), and

(3) a significant increase in prices of production processes heavily dependent on covered minimum-wage workers.

Wessels found that minimum-wage increases had exactly the opposite effect:

(1) participation rates went down,

(2) quit rates went up, and

(3) prices did not rise appreciably—which are findings consistent only with the view that minimum-wage increases make workers worse off.

McKenzie was the first economist to argue that a minimum wage increase may actually reduce the labour supply of menial workers. Employment in menial jobs may go down slightly in the face of minimum-wage increases not so much because the employers don’t want to offer the jobs, but because fewer workers want these menial jobs that are offered.

The repackaging of monetary and non-monetary benefits, greater work intensities and fewer training opportunities make these jobs less attractive relative to their other options. This reduction in labour supply by low skilled workers is why the voluntary quit rate among low-wage workers goes up, not down, after a minimum wage increase. As McKenzie explains

Economists almost uniformly argue that minimum wage laws benefit some workers at the expense of other workers.

This argument is implicitly founded on the assumption that money wages are the only form of labour compensation.

Based on the more realistic assumption that labour is paid in many different ways, the analysis of this paper demonstrates that all labourers within a perfectly competitive labour market are adversely affected by minimum wages.

Although employment opportunities are reduced by such laws, affected labour markets clear. Conventional analysis of the effect of minimum wages on monopsony markets is also upset by the model developed.

McKenzie argues that not accounting for offsetting behaviour led to a fundamental misinterpretation in the empirical literature on the minimum wage. That literature shows that small increases in the minimum wages does not seem to affect employment and unemployment by that much.

…. wage income is not the only form of compensation with which employers pay their workers. Also in the mix are fringe benefits, relaxed work demands, workplace ambiance, respect, schedule flexibility, job security and hours of work.

Employers compete with one another to reduce their labour costs for unskilled workers, while unskilled workers compete for the available unskilled jobs — with an eye on the total value of the compensation package. With a minimum-wage increase, employers will move to cut labour costs by reducing fringe benefits and increasing work demands…

Proponents and opponents of minimum-wage hikes do not seem to realize that the tiny employment effects consistently found across numerous studies provide the strongest evidence available that increases in the minimum wage have been largely neutralized by cost savings on fringe benefits and increased work demands and the cost savings from the more obscure and hard-to-measure cuts in nonmoney compensation.

McKenzie is correct in arguing that the empirical literature on the minimum wage is dewy-eyed. The first assumption about any regulation is the market will offset it significantly. In the course of undoing the direct effects of the regulation, there will be unintended consequences such as the remixing of wage and nonwage components of remuneration packages of low skilled workers covered by the minimum wage.

Recent Comments