Richard Tol @ CATO: The road from Paris: whither climate policy? https://t.co/knJBf1liTy

— Judith Curry (@curryja) November 1, 2015

Richard Tol on The road from Paris: whither climate policy?

03 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, global warming Tags: climate alarmism, Richard Tol

@RichardTol on energy pollution trade-offs

05 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in energy economics, environmental economics, global warming Tags: air pollution, Richard Tol, trade-offs

BBC @RHarrabin on RE emissions pollution etc, good summary of complexity by @RichardTol

bbc.co.uk/news/science-e… http://t.co/xQNGzlpUSe—

Roddy Campbell (@Roddy_Campbell) September 29, 2015

Economic impact of global warming: new evidence

18 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, development economics, environmental economics, global warming, growth disasters, growth miracles, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: climate alarmism, global warming, Richard Tol

A nice summary of the latest research showing that once again the welfare cost of climate change is small except under the most extreme scenarios.

2% of national income is not something to declare a national emergency over unless you are in a very poor country.

Richard Tol also mentions that there has only been 27 studies of the economic costs of climate change:

Twenty-seven estimates is a thin basis for any conclusion. Researchers disagree on the sign of the net impact; climate change may lead to a welfare gain or loss. At the same time, researchers agree on the order of magnitude. The welfare change caused by climate change is equivalent to the welfare change caused by an income change of a few percent.

- That is, a century of climate change is about as good/bad for welfare as a year of economic growth.

As Tol wrote elsewhere, the reason why there are so few studies of the welfare cost of global warming is governments and bureaucracies do not like the small numbers they yield so they pre-emptively do not fund such research.

Few economists work full-time on the economics of climate change as their research results are too moderate to win repeat business and further research grants. Importantly, there is vicious criticism of what you say. Much better to just work on other topics.

One of the great tactical victories of the climate activists, I resisted the temptation to call them climate alarmists, is they keep going on about the science is settled and whether you are accepting the scientific results.

I have long argued let the science be settled, only the economics matters. The climate change activists do not want to talk about the economics that much except for the estimates by that political hack Lord Stern. Lord Stern has been on the losing side of history ever since he wrote a bad review of PT Bauer’s Dissent on Development where he said:

Dissent on Development is not a valuable contribution to the study of development.

The Stern Review puts the costs of unmitigated climate change at 5–20% of GDP (now and forever). The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) finds differently.

HT: Lorenzo M Warby

Citations to 5 climate economists

14 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, global warming Tags: climate alarmists, global warming, Richard Tol

Citations to 5 climate economists according to Scopus #climateeconomics http://t.co/3W2u5Wvosq—

Richard Tol (@RichardTol) July 10, 2015

The economic models of global warming are crude, unsophisticated, static, and untested by data?

17 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

On the beneficial effects of climate change

05 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

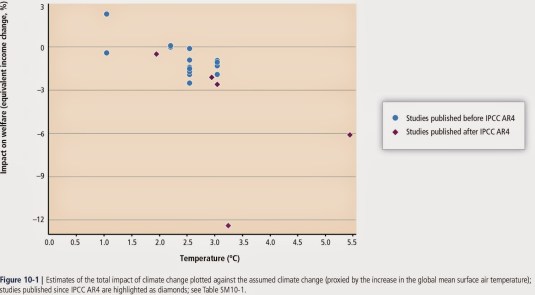

The above figure is as it appears in the final, published version of Chapter 10 of the Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

via Richard Tol.

IPCC report shows Stern inflated climate change costs by Richard Tol

16 Oct 2014 12 Comments

in environmental economics, global warming Tags: climate alarmism, global warming, Nicolas Stern, Richard Tol

How much does climate change cost? What will be the impact on our wallets?

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Working Group II has concluded that global warming of 2.5˚C would cost the equivalent to losing between 0.2-2.0% of annual income.

This seems in sharp contrast to the Stern Review of the Economics of Climate Change, which found it would cost 5-20%. How can that be?

The Stern Review was prepared by a team of civil servants and never reviewed (before publication) by independent experts. Some argue that the Stern Review served to bolster Gordon Brown’s credentials with the environmental wing of the Labour Party in preparation for his transition to party leader and prime minister. And in fact next week IPCC Working Group III will conclude that the Stern Review grossly underestimated the costs of bringing down greenhouse gas emissions.

While interested parties can self-publish whatever they want, such informally published grey literature has no place in the IPCC’s work. Although the Stern Review’s findings were not included in the IPCC’s current, Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), the Stern Review draws heavily on the climate change impact estimates of Chris Hope of Cambridge University, whose numbers are peer-reviewed, and were included in the IPCC’s work. Hope calculated a economic loss of 0.9%, slightly lower than the IPCC’s central estimate of 1.1%. So the Stern Review and IPCC AR5 do not contradict one another. If anything, the Stern Review is slightly more optimistic.

Playing with numbers

So how did the Stern Review reach its figure of 5%-20% of income, when in fact its calculations started with an estimate of less than 1%? The reason is an arcane bit of welfare economics. Dr Hope’s 0.9% is a conventional impact estimate. If the world warmed by 2.5˚C, the average person would feel as if they had lost 0.9% of her income. If the world warmed by more, the impact would be higher; if warming is less, the impact is lower.

The Stern Review’s 5% is generated like an annuity, taking a stream of payments that vary over time (in this case the predicted impact of climate change) and converting it into fixed annual payments. The Stern Review thus replaces the impact of more than 200 years of climate change – effects that start low and end high – with a number that is the same for each year. Most people find it confusing to replace numbers that vary over time with a single fixed number.

In order to calculate an annuity economists apply a discount rate, effectively representing the change in value of money over time. The Stern Review (as it was originally published in 2006) uses a discount rate of about 1.4% – far below what most people use, and indeed far lower than the official discount rate of Her Majesty’s Treasury of 3.5% (and falling further to 1% for those effects more than three centuries into the future). Using such a low discount rate inflates the annuity, and so the reported costs of climate change.

Stern’s argument for a low discount rate is a paternalistic one. People’s value judgements are wrong, according to the Stern Review, and the government has the right to overrule them. Stern puts himself in the position of a colonial ruler, governing the savages against their will – but in their own interest, of course.

The costs of uncertainty

Stern’s 5% figure also reflects the uncertainties about future climate change and its impact on our welfare. Combined with the low discount rate, this means that the headline number of the Stern Review is dominated by unlikely events in 200 years’ time. It does not reflect climate changes’ impact in the near term, or even the best estimate over a century. It is, by and large, a prediction based on the worst case scenario of two centuries from now.

Unfortunately, this worst case is internally inconsistent. It assumes both high greenhouse gas emissions and high vulnerability to the effects of climate change. That does not make sense. Essentially, it assumes that, for example, Africans will be rich enough to drive highly emitting SUVs, but too poor to buy mosquito nets to protect their children against malaria spread by increased numbers of insects that the warmer, wetter climate global warming would bring.

So while Stern reports a range of 5-20%, those figures do not truly represent upper and lower bounds. The 5% is their best estimate, reflecting all uncertainties. The 20% is an arbitrary number – it is based on assumptions on greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and climate impacts that the authors themselves find less credible.

Both studies agree that the economic impact of climate change is small – half a century of climate change at this rate would do perhaps as much damage as losing one year of economic growth. Unfortunately, the Stern Review hides this reasonably optimistic conclusion behind accounting tricks and dubious assumptions, creating a sense of disagreement that is not there.

via theconversation.com under Creative Commons Licence

Stern 2.0 takes climate policy analysis to a new level of exaggeration by Richard Tol

27 Sep 2014 2 Comments

in economics of climate change, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming Tags: global warming, Nicholas Stern, Richard Tol, Stern 2.0, Stern report

Nick Stern is back with another report on climate change – colloquially known as Stern 2.0. It’s another offering from the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. Since his 2006 review, Stern has been regularly in the news, claiming climate change is worse than we thought. The new report fits the mould.

The summary was released before the main report and we are invited to believe its findings without inspecting the evidence. It seems, though, that Stern has produced another far-fetched piece of work.

The new report makes three claims, none of which stand up: that climate policy stimulates economic growth; that climate change is a threat to economic growth; and an international treaty is the way forward.

Climate policy and economic growth

“Well-designed policies … can make growth and climate objectives mutually reinforcing,” the report claims.

The original Stern Review argued that it would cost about 1% of global GDP to stabilise the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases around 525ppm CO2e. In its report last year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put the costs twice as high. The latest Stern report advocates a more stringent target of 450 ppm and finds that achieving this target would accelerate economic growth.

This is implausible. Renewable energy is more expensive than fossil fuels, and their rapid expansion is because they are heavily subsidised rather than because they are commercially attractive. The renewables industry collapsed in countries where subsidies were withdrawn, as in Spain and Portugal. Raising the price of energy does not make people better off and higher taxes, to pay for subsidies, are a drag on the economy.

Climate policy need not be expensive. Study after study has shown that it is possible to decarbonise at a modest cost and Stern has missed an opportunity to point this out.

But low-cost climate policy is far from guaranteed – it can also be very, very expensive. Europe has adopted a jumble of regulations that pose real costs for companies and households without doing much to reduce emissions. What is the point of the UK carbon price floor, for instance? Emissions are not affected because they are capped by the EU Emissions Trading Systems, but the price of electricity has gone up.

The subsidies and market distortions that typify climate policy do, of course, create opportunities for the well-connected to enrich themselves at the expense of the rest of society. Perhaps Stern 2.0 mistook rent seeking for wealth creation.

Climate change and economic growth

The report says that if, in the long run, “climate change is not tackled, growth itself will be at risk.”

The new report claims climate change would be a threat to economic growth. The original Stern Review argued that the damage would be 5-20% of global income. In the worst case, we would not be four times as rich by the end of the century, but only 3.8 times. The IPCC reckons Stern 1.0 exaggerated the impacts by a factor 10 or more, while the new Stern report agrees that the old Stern was off by an order of magnitude, but in the opposite direction.

Over the past two decades, economists have re-investigated the relationship between economic development and geography. This has not led to a revival of the climate determinism of Ellsworth Huntington – the Yale professor who argued that a nation’s prosperity could be predicted by its location and climate. On the contrary, most research finds that climate plays at most a minor role in economic growth, and that the impact of climate is moderated by technology and institutions. Just consider Iceland and Singapore. Stern 2.0 goes against the grain of a large body of literature.

International treaties

“A strong … international agreement is essential,” the Stern report says, calling for an international treaty with legally binding targets. Albert Einstein defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. Since 1995, the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change have met year-after-year to try and agree on legally binding targets – and they have failed every time.

The reasons are simple. It is better if others reduce their emissions but you do not. No country likes to be bound by UN rules for its industrial, agricultural and transport policies. The international climate negotiations have been successful in creating new bureaucracies, but not in cutting emissions.

Stern also argues that “[d]eveloped countries will need to show leadership.” The EU has led international climate policy for two decades, but without winning any followers. The broken record that is Stern 2.0 is unlikely to inspire enthusiasm for more expensive energy.

A way forward

The Stone Age did not end because we ran out of stones, but because we found something better: bronze. The fossil fuel age will end when we find an alternative. The current renewables are simply not good enough – except for the happy few who profit from government largesse.

The environmental movement’s aversion to nuclear power and shale gas increases emissions and creates an impression of Luddism, whereas climate policy should focus on accelerating technological change in energy.

The unfounded claims in Stern’s new report do not build the confidence that investors and inventors need to take a punt on a carbon-free future. Exaggeration is great for headlines, but sober analysis is more convincing in the long run.

via theconversation.com under Creative Commons Licence

The costs of global warming and other government statistics – Updated

11 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, global warming Tags: Bjørn Lomborg, global warming, Richard Tol, Yes Prime Minister

Figure 1. The 14 estimates of the global economic impact of climate change, expressed as the welfare-equivalent income loss, as a functions of the increase in global mean temperature relative to today

Source: Richard Tol

The recent IPCC report found that the temperature rise that we are expected to see sometime around 2055-2080 will create a net cost of 0.2-2% of GDP. The UK, Japan, and the US wanted this rewritten or stricken.

The IPCC report showed that strong climate policies would be more expensive than claimed as well – costing upwards of 4% of GDP in 2030, 6% in 2050, and 11% by 2100.

Politicians tried to delete or change references to these high costs. British officials said they wanted such cost estimates cut because they “would give a boost to those who doubt action is needed.”

Sir Humphrey: No, no… Blurring issues is one of the basic Ministerial skills.

Jim: Oh, what are the others?

Sir Humphrey: Delaying decisions, dodging questions, juggling figures, bending facts and concealing errors.

and more from Yes Minister:

Seven ways of explaining away the fact that North-West region has saved £32 million while your department overspent:

a. They have changed their accounting system in the North-West.

b. Redrawn the boundaries, so that this year’s figures are not comparable.

c. The money was compensation for special extra expenditure of £16 million a year over the last two years, which has now stopped.

d. It is only a paper bag saving, so it will have to be spent next year.

e. A major expenditure is late in completion and therefore the region will be correspondingly over budget next year. (Known technically as phasing – Ed)

f. There has been an unforeseen but important shift in personnel and industries to other regions whose expenditure rose accordingly.

g. Some large projects were cancelled for reasons of economy early in the accounting period with the result that the expenditure was not incurred but the budget had already been allocated.

HT: Bjørn Lomborg and wattsupwiththat

Addendum

http://www.reddit.com/user/pnewell was good enough on the climate sceptics subreddit to point out that there is an updated version of the graph I posted at the top that includes corrections for gremlins in Richard Tol’s original paper.

His response reminds me of another passage from Yes Minister where prime ministerial candidate Jim Hacker is arguing with a European commission official about butter mountains.

Hacker said in one room a European commission official was subsidising people to produce milk, while in the next room another official is subsidising people to destroy it.

The response of this European union official was to say that was not true. Hacker asked how it was not true. He was told that the two officials were not on the same floor, the other official paying people to take the milk away is on the next floor.

The main body of my post is:

- about propaganda tactics to discredit criticism and suppress inconvenient facts, and

- the IPCC report facts that even if global warming is a problem, doing anything about it makes us even worse-off.

Richard Tol on the political pre-requisites to a carbon neutral economy

05 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, global warming Tags: global warming, Richard Tol

Richard Tol: IPCC again

27 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in economics, environmental economics, global warming, politics Tags: global warming, IPCC, Richard Tol

Richard Tol reports that landlocked countries vigorously protested at IPCC meetings that they too would suffer from sea level rise!

This was because the international climate negotiations of 2013 in Warsaw concluded that poor countries might be entitled to compensation for the impacts of climate change.

The assessment of the size of those impacts and hence any compensation led to an undignified bidding war among delegations – my country is more vulnerable than yours. Landlocked countries had no intention of missing out.

The IPCC is a typical multilateral meeting process from Tol’s description:

- Many countries send a single person delegation.

- Some countries can afford to send many delegates.

- They work in shifts, exhausting the other delegations with endless discussions about trivia, so that all important decisions are made in the final night with only a few delegations left standing.

Naturally, all inconvenient truths are vetoed, as Tol explains, listing the following omissions and redrafts of the Summary for Policy Makers:

- it omits to say that better cultivars and improved irrigation increase crop yields;

- it shows the impact of sea level rise on the most vulnerable country, but does not mention the average;

- it emphasizes the impacts of increased heat stress but downplays reduced cold stress; and

- it warns about poverty traps, violent conflict and mass migration without much support in the literature.

Tol then aptly states his position on it all:

Alarmism feeds polarization.

Climate zealots want to burn heretics of global warming on a stick.

Others only see incompetence and conspiracy in climate research, and nepotism in climate policy.

A polarized debate is not conducive to enlightened policy in an area as complex as climate change – although we only need a carbon tax, and a carbon tax only, that applies to all emissions and gradually and predictably rises over time.

HT: Catallaxyfiles

Climate policy targets revisited | Richard Tol

26 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economics of climate change, environmental economics, environmentalism, politics Tags: global warming, Richard Tol

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report estimates lower costs of climate change and higher costs of abatement than the Stern Review. However, current UN negotiations focus on stabilising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases at even lower levels than recommended by Stern.

This column argues that, given realistic estimates of the rate at which people discount the future, the UN’s target is probably too stringent.

Moreover, since real-world climate policy is far from the ideal of a uniform carbon price, the costs of emission reduction are likely to be much higher than the IPCC’s estimates.

PRTP is the preferred rate of time preference used in net present value calculations.

The incentives to research the economics of global warming – the minimum wage edition

02 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economics of natural disasters, environmental economics, personnel economics, Public Choice Tags: David Card, global warming, IPCC, Richard Tol

David Card’s research suggested that small rises in the minimum wage do not reduce employment by much.

He said that he did not do much further research in the area because people were so personally unpleasant for him:

I haven’t really done much since the mid-’90s on this topic. There are a number of reasons for that that we can go into.

I think my research is mischaracterized both by people who propose raising the minimum wage and by people who are opposed to it.

… it cost me a lot of friends. People that I had known for many years, for instance, some of the ones I met at my first job at the University of Chicago, became very angry or disappointed.

They thought that in publishing our work we were being traitors to the cause of economics as a whole.

I also thought it was a good idea to move on and let others pursue the work in this area. You don’t want to get stuck in a position where you’re essentially defending your old research.

You need a thick hide and academic tenure to do research into the minimum wage these days. There are plenty of research topics that do not cost you friends.

Richard Tol has pointed out that maybe 20 or so academic economists work on climate change on a regular basis. Many of the key survey papers are written by the same few people, including him.

The reasons were that inter-disciplinary works is looked down on in the economics profession and government agencies do not like what economic research says about the costs and benefits of global warming so they pre-emptively do not fund it.

Richard Tol quit as the lead author of an economics chapter of the most recent of the IPCC report after a dispute about research techniques. Tol had been invited to help in the drafting in a team of 70 and was also the coordinating lead author of a sub-chapter about economics.

When he dissented about the quality and alarmist nature of the economics of the IPCC reports, they smeared him so badly as a fringe figure that you wonder why they hired him in the first place.

The co-chair of the IPCC working group that produced the report, said Richard Tol was outside the mainstream scientific community and was upset because his research had not been better represented in the summary:

“When the IPCC does a report, what you get is the community’s position. Richard Tol is a wonderful scientist but he’s not at the centre of the thinking. He’s kind of out on the fringe,” Professor Field said before the report’s release.

You cannot, on the one hand, say that you have hired the best and the brightest to work on “the greatest moral, economic and social challenge of our time” and then say that a dissenting member is a fringe figure. If that was true, rather than a smear, he would never have been hired in the first instance.

Nor would Richard Tol have been asked to write a 2009 survey of the economics of climate change for the leading surveys journal in all of economics – The Journal of Economic Perspectives. This fringe figure said in that survey in 2009 that:

Only 14 estimates of the total damage cost of climate change have been published, a research effort that is in sharp contrast to the urgency of the public debate and the proposed expenditure on greenhouse gas emission reduction.

These estimates show that climate change initially improves economic welfare. However, these benefits are sunk.

Impacts would be predominantly negative later in the century.

Global average impacts would be comparable to the welfare loss of a few percent of income, but substantially higher in poor countries.

Still, the impact of climate change over a century is comparable to economic growth over a few years.

The IPCC hired Tol because their economics of global warming chapters would have lacked credibility if he had not been on the team. LBJ said that it is better to have someone inside the tent pissing out than outside pissing in.

Richard Tol even has an academic stalker:

Bob Ward, has reached a new level of trolling. He seems to have taking it on himself to write to every editor of every journal I have ever published in, complaining about imaginary errors even if I had previously explained to him that these alleged mistakes in fact reflect his misunderstanding and lack of education. Unfortunately, academic duty implies that every accusation is followed by an audit. Sometimes an error is found, although rarely by Mr Ward.

Richard Tol blogs at http://richardtol.blogspot.co.nz/

Recent Comments