Your driving future

20 Oct 2021 Leave a comment

in law and economics, property rights, transport economics Tags: common law, driverless cars, tort law

The Truth About The McDonald’s Coffee Lawsuit

14 Mar 2017 Leave a comment

in law and economics Tags: tort law

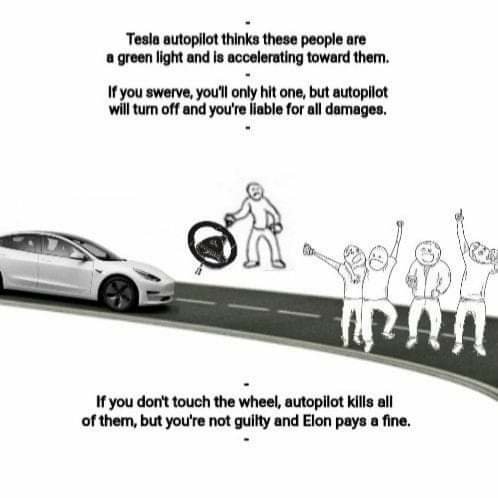

Tesla’s autopilot

16 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in law and economics, transport economics Tags: creative destruction, driverless cars, tort law

The herd immunity role of #vaccinations explained

16 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, health economics, politics - New Zealand, public economics Tags: Anti-Science left, anti-vaccination movement, best shot public goods, cheap riders, common law, free-riders, good shot public goods, herd immunity, measles, New Zealand Greens, public goods, quackery, tort law, vaccinations, vaccines

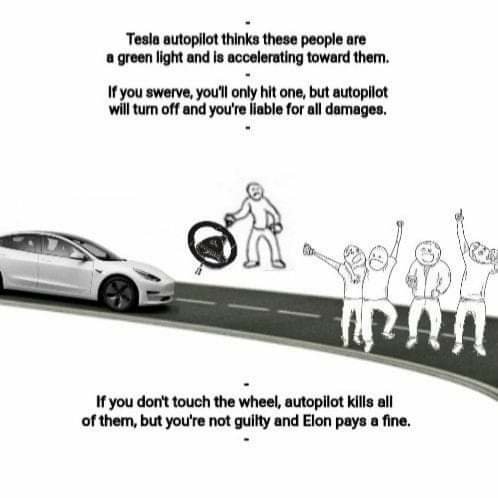

Some public goods can be not provided much at all if even a few do not contribute – free ride. These are called weakest shot public goods. The link in the chain is only as strong as the weakest link for some public goods. The fighting against communicable diseases is an example of that.

The classic example given by that brilliant applied price theorist Jack Hirschleifer is a dyke or a levee wall around a town. It is only as good as the laziest person contributing to its maintenance on their part of the levee wall. Vicary (1990, p. 376) lists other examples:

Similar examples would be the protection of a military front, taking a convoy across the ocean going at the speed of the slowest ship, or maintaining an attractive village/landscape (one eyesore spoils the view).

Many instances of teamwork involve weak-link elements, for example moving a pile of bricks by hand along a chain or providing a theatrical or orchestral performance (one bad individual effort spoils the whole effect.)

Another example of weakest shot public goods is community cooperation after disasters. The quality of the public good provided is equal to the contribution of the weakest person who may start a criminal rampage despite the good efforts of everyone else.

People tend to be more cooperative after natural disasters. They realise their contribution is more important than normal to the maintaining of the social fabric which is currently hanging by a thread.

People tend to be more cooperative after natural disasters. They realise their contribution is more important than normal to the maintaining of the social fabric which is currently hanging by a thread.

Vaccinations are example of a weakest shot public good. The quality of herd immunity depends fundamentally on just about everybody contributing by getting vaccinated. Not all public goods depend on the some of those contributions made. In some cases just a few people choosing to free ride can greatly undermine the public interest.

The reverse of a weakest shot public good is best shot public goods. Example of this is the development of vaccines themselves. The public good is only as good as the best effort at developing the new vaccine with all the others efforts pointless because the best of the vaccines is chosen.

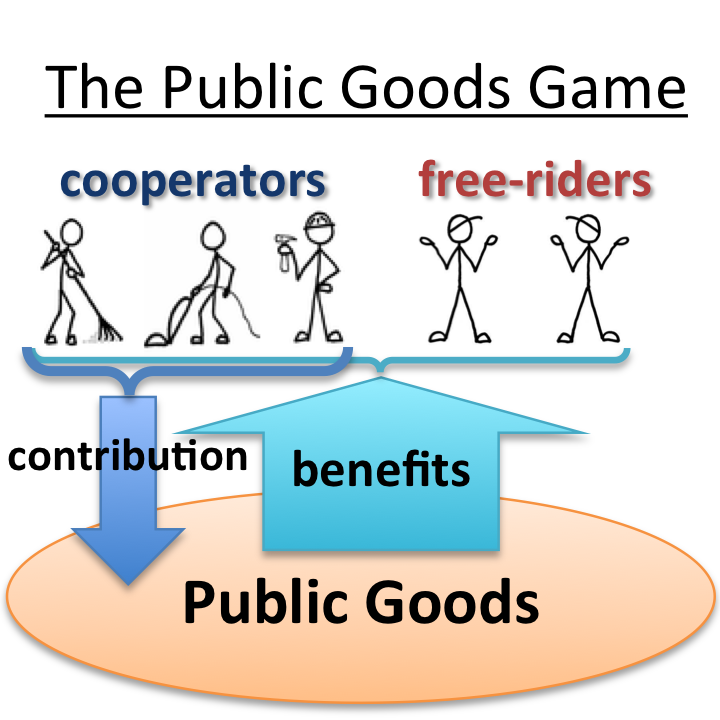

The most curious people in New Zealand to oppose measures to address the under provision of weakest shot public goods are the New Zealand Greens.

https://twitter.com/KevinHague/status/642505850360213505

The Greens are usually the 1st to stress the importance of communities working together for the common good.

https://twitter.com/KevinHague/status/642530277177192448

Herd immunity protects those who cannot be safely vaccinated including new babies, those for whom the vaccine fails, which occasionally happens, and those with compromised immunity such as adults receiving chemotherapy.

Deliriously hot @guardian sim shows why anti-measles jabs help protect your whole community gu.com/p/45f7e/stw http://t.co/H31ZKbXkqg—

Info=Beautiful (@infobeautiful) February 05, 2015

We are all in this together. It is time for the New Zealand Greens to stop pandering to those are only think of themselves and what a free ride on others including the very sick and new babies.

Source: NOVA | What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity requires vaccination rates of about 94%. The near universal vaccination rates required for herd immunity are to smaller margin to pander to an awkward squad who do not want to vaccinate despite the harm they do to others.

Harm to others is grounds and has always been grounds for public policy and public health interventions. Instead, the Greens are anti-science, anti-public health.

Measles is the most contagious disease known to man. Seven children died in New Zealand in the last measles outbreak in 1991. The dead are already too many from the anti-vaccination quacks and cranks.

Environmental Law 101 | Richard Epstein

05 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, law and economics, liberalism, property rights, Richard Epstein Tags: environmental law, law of nuisance, Richard Epstein, tort law

Back in 1999, Richard Epstein wrote a great summary of what should be environmental law from an old common law perspective, from a classical liberal perspective, and a pragmatic economic libertarian perspective:

Stated bluntly, nothing in the theory of property rights says that my property is sacred while everybody else’s property is profane. That single constraint of parity among owners should lead every owner to think hard…

This recognition of the noxious uses of private property is the source of the common law of nuisance.

That law dates from medieval times, certainly by 1215, at the time of the Magna Carta. It is no new socialist or environmentalist creation for the twentieth century.

When the common law of nuisance restricts the noxious use of property, it benefits not only immediate neighbours but the larger community. If I enjoin pollution created by my neighbour, others will share in the reduction of pollution.

Simply by using private actions, we have built a system for environmental protection that goes a long way toward stopping the worst forms of pollution.

Epstein does not stop there. He recognises as he should that the common law of nuisance is not enough to stop all problems of pollution:

Yet before we leap for joy, we must recognize that private actions are not universally effective in curbing nuisances.

Sometimes pollution is widely diffused—waste can come from many tailpipes, not just one—so that no one can tell exactly whose pollution is causing what damage to which individuals.

Under those circumstances, private enforcement of nuisance law can no longer control pollution…

We do not change the substantive standards of right and wrong, but we do use state regulation to fill in the gaps in private enforcement.

But often when individuals worry about their local environments, they’re not particularly happy to treat the nuisance law, however enforced, as the upper bound of their personal protection.

They want (especially as their wealth increases) more by way of aesthetics and open spaces. Fortunately, our legal system has a way to accommodate these newer demands.

One of our most important land-use control devices is the system of covenants by which all the holders of neighbouring lands agree among themselves and for their successors in title

Covenants might work in Greenfields developments in modern cities. But they really doesn’t work in managing land use conflicts in the inner city where regulation is been used to substitute the covenants for many decades.

Epstein’s ideal for modern environmental law is:

In sum, the system of public and private enforcement of nuisances and public and private purchases of environmentally sensitive sites is the way that sound environmental policy should proceed.

Recent Comments