The decaying USSR somewhat unexpectedly cancelled its extensive trade contracts with Finland on 18th December 1990.

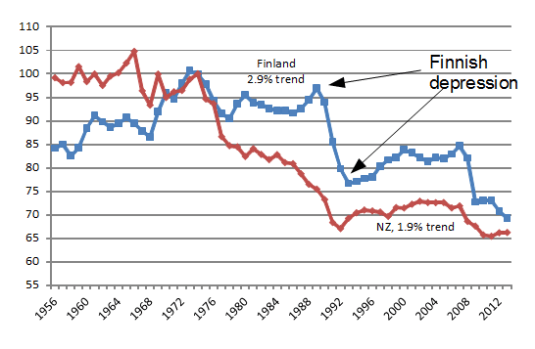

By 1993, Finland was in the deepest depression seen in an industrialised country since the 1930s up to that time (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012). Real GDP per working age Finn dropped by 12 per cent in two years, see Figure 1; real growth against trend dropped by 19 per cent, see Figure 2.

Figure 1: Real GDP per New Zealander and Finn aged 15-64, 2010 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1970-2013

Source: OECD Stat Extract and the Conference Board, Total Database, September 2011.

Figure 2: Real GDP per New Zealander and Finn aged 15-64, 2010 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, trend corrected, 1970-2013

Source: OECD Stat Extract and the Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014.

Note: the trend rate of real GDP growth per Finn aged 15-64 was 2.9 per cent for 1970–1990.

Finland is a natural experiment illustrating the behaviour of a small open economy after a large external shock affecting energy costs and the allocation of resources between sectors after the loss of highly privileged export market access. The same thing happened to New Zealand when the Britain entered the common market in 1973.

Kehoe and Ruhl (2003) attributed the 1970s total factor productivity collapse in New Zealand shown in Figure 2 to a massive change in trade patterns after the entry of the UK into the then European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 – British entry into the common market.

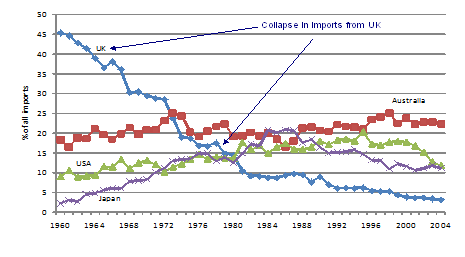

Figures 3 and 4 show that the UK moved from the majority trading partner up in the mid-1960s to making up barely 10 per cent of either exports or imports by 1980. Australian and Japanese exports were small until the 1970s and the USA picked up little of the slack.

Figure 3: New Zealand export shares, 1950-2005

Source: Briggs 2007.

Figure 4: Imports from the UK, Australia, USA and Japan, 1960-2004

Source: Statistics New Zealand Long Term Data Series, no date.

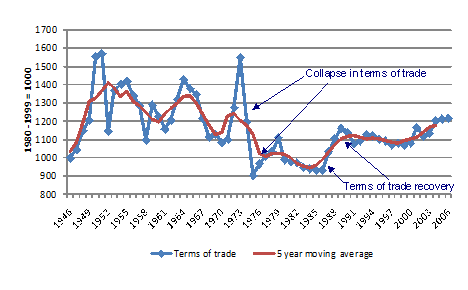

Figure 5 shows that the terms of trade started falling in the mid-1960s with the wool price collapse, spiked in the early 1970s, and collapsed from 1974 and stayed low until the mid-1980s recovery. Kehoe and Ruhl (2003) found that the terms of trade fell by 30 per cent between 1974 and 1980.

Figure 5: New Zealand terms of trade, 1946-2006

Source: Briggs 2007.

The collapse of the global wool market on 24 November 1966 saw New Zealand lose an eighth of its export income overnight (Redell and Sleeman 2008). The real price of wool fell by 20 per cent in 1967, by 20 per cent in 1968; a sharp recession ensued in the late 1960s (Dalziel 2002).

Kehoe and Ruhl (2003) attributed the terms of trade collapse to the UK’s entry into the EEC, the loss of UK tariff preferences in 1977, and the imposition of import quotas by the EEC.

The collapse of trade with the UK also coincided with the 1973 oil price shock and a major drought – the second driest year on record was 1972-73 (Redell and Sleeman 2008). New Zealand’s driest year on record coincided with the East Asian financial crisis (Redell and Sleeman 2008).

The OPEC oil shocks in 1973 did compound matters arising from loss of access to British markets as it entered the common market, but these very large price rises were common to all oil importing countries.

To explain the large drop in total factor productivity after 1973 in New Zealand, shocks that are country-specific in the nature or common global shocks that affected productivity in New Zealand to an unusually large degree must be identified for further analysis. It is unwise to explain large differences in the productivity performances of New Zealand with factors that they have in common with other comparable countries such as the 1970s OPEC oil price shocks.

Kehoe and Ruhl (2003) suggested that New Zealand prior to 1973 was a colonial farm, with preferential terms with the UK for exports and imports, bulk purchase agreements and extensive import controls and export subsidies.

These preferences followed the 1932 Ottawa Conference – the British Dominions secured preferential access for exports in return for lowering tariffs on UK imports (Rae et al. 2006). The UK export premiums capitalised into the value of New Zealand farms and had to be written off after the UK entered the EEC (Easton 2009).

In common with the loss of access to British markets by New Zealand, the depression in Finland led to dramatic changes in the Finnish economy. These included increased export orientation, the rise of Nokia and the telecommunications industry, and a fall in unionization rates and policy reforms such as the adoption of inflation targeting, reduced taxes and more decentralized wage setting (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

Through a complex set of five year barter agreements for both exports and for imports, some Finnish sectors specialised in supplying Soviet markets, none were isolated from Soviet trade (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

These barter arrangements with the USSR skewed Finnish manufacturing and investment to particular industries, and allowed Finland to export non-competitive products in return for cheap energy imports. The Finnish mark-up on Soviet exports over other markets was 10 – 36 per cent (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

This Finnish trade pattern is similar to New Zealand with pre-1973 UK. New Zealand was a colonial farm, Finland was a Soviet adjunct. The USSR accounted for 20 to 25 per cent of Finnish trade (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

Finnish dependence on the Soviet Union represented a smaller share of trade than between pre-1973 UK and New Zealand. In the case of New Zealand, a majority of its trade was to the mother country – see figure 4.

Another important distinguishing feature is the reduced access of New Zealand to UK markets as it integrated into the common market was gradual, not sudden.

This gradual unfolding of the market access shock for New Zealand compares to the Finns where overnight Finland lost its largest trading partner and the source of 80 per cent of its energy needs, which were all long supplied at a 10 per cent or more discount (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

Finnish taxes on labour and capital incomes also increased in the period leading up to 1991 as did Finnish government consumption expenditure (Conesa et al. 2007).

From 1989 to 1992, the Bank of Finland raised real short-term interest rates from two per cent to 12 per cent to defend a fixed exchange rate after many Finnish households and businesses had accumulated large debts (Kiander 2004). The monetary contraction and the collapse of Soviet trade combined to turn the net worth of many debtors negative. A massive banking crisis ensued.

The exchange rate peg was abandoned in 1992 during the European Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis of 1992-93, which was brought on by the fiscal cost of German unification. After floating, the Finnish markka depreciated 30 per cent (Kiander 2004).

The loss of most of its trade with the USSR required Finland to undertake a costly restructuring of specialised manufacturing sectors and adjust to a sudden, large and permanent increase in energy prices. Oil imports from the USSR fell from 8.2 million tons in 1989 to 1.3 million tons in 1992; exports to the USSR fell 84 per cent over the same period (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

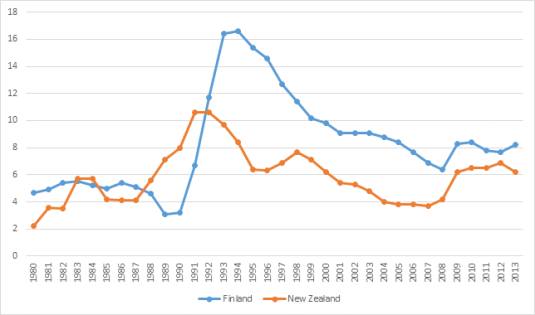

Real GDP per working age Finn dropped by 20 per cent against trend in two years – see Figure 2. Finnish share and housing prices and investment more than halved over the same period (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012; Conesa et al. 2007). The Finnish unemployment rate spiked from 6½ per cent in 1991 to 16 per cent in 1993 – see figure 6.

Figure 6: New Zealand and Finnish unemployment rates, 1980-2013

The impact of higher energy prices and the restructuring on manufacturing specialised in Soviet trade on the remaining 95 per cent of the economy was greatly amplified by the highly centralised nature of the Finnish labour market (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

About 85 per cent of workers belonged to unions and about 95 per cent of workers were covered by collective agreements which govern each job classification with considerable particularity (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012). Dickens et al. (2007) classed Finland as has having one of the greatest downward wage rigidities of all OECD member countries.

Finnish unions did not agree to cut nominal wages in 1992-1993, which was the peak year of the depression (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012). There was mass and sharply rising unemployment in Finland at the time. Finnish trade unions focused on protecting those union members with a job rather than those competing for a job.

Gorodnichenko et al. (2012) estimated that the recession in Finland after the loss of trade access to the USSR would have been short and shallow if the Finnish wages were fully flexible.

The Finnish depression of 1991 to 1993 was the most serious economic crisis in its peacetime history; and by many measures, it was a depression more severe than the depression of the 1930s (Honkapohja and Koskela 1999; Honkapohja et al.; 2009).

The drop in GDP per working age Finn against trend was larger in the 1991-1993 depression than in 1932, which was the peak year of the Great Depression in Finland (Conesa et al. 2007).

Finland resumed high GDP growth in 1994, see Figure 1 and Figure 2. Like New Zealand, Finland had to find new trading partners to replace an old staple.

Unlike New Zealand, the loss of a major export market was not a permanent scar on Finnish productivity. The structure of the Finnish economy transformed. The forestry and engineering industries became less important and high-tech sectors such as the mobile phones industry dominated the recovery process (Kalela et al. 2001).

Finnish corporate and capital taxation were reformed in 1993. A 25 per cent tax rate was introduced for profits, capital income and capital gains. Finnish taxes on labour incomes and welfare benefits were gradually reduced over the 1990s (Kiander 2004; Conesa et al. 2007).

What the 1991-93 Finnish depression and the Lost Decades in New Zealand in the 1970s and 1980s have in common is the reallocation of resources across firms and sectors after terms of trade shocks can be particularly costly in the presence of sticky wages and prices.

The collapse of Soviet trade sent Finland into a deep depression through the loss of markets and an inability to adjust wages and prices quickly enough to buffer the loss of a key export market and source of cheap source of energy supplies (Gorodnichenko et al. 2012).

The loss of preferential trading terms with the UK after it joined the EEC in 1973 was more gradual. The membership negotiations for the UK lasted a number of years and timing of processes of joining and the impactions for trade access could be much better anticipated by New Zealand.

Nonetheless, a restructuring of the New Zealand economy was required albeit with much better and longer advance notice that was the case with Finland and its sudden cancellation of its trade contracts with the then USSR.

Much of the 1970s and early 1980s in New Zealand was spent on economic policies that resisting structural change.

This was rather than adopting economic policies that facilitated and enabled the adaptation of the structure of the economy to the inevitability of new trade market outlook and the need to diversify exports and import sourcing to a range of new countries.

Finland shows that the reallocation of resources across sectors can be particularly costly in the presence of sticky wages and/or prices. Large increases in unemployment and large falls in productivity and production can follow.

This also happened in New Zealand after the 1973 oil price shock and the loss of UK markets. The puzzle is Finland rebounded after a very deep but short depression.

New Zealand instead experienced a long depression between 1972 and 1992, albeit without a sudden increase in unemployment – see figures 1, 2 and 6. The low unemployment in the 1970s and early 1980s in New Zealand may have been why New Zealand voters and political parties was able to hold out against economic reform.

One of the key aspects of economic reform in New Zealand in the mid to late 1980s was a crackdown on featherbedding in public sector jobs – jobs that didn’t produce much.

A much greater flexibility in both Finland and New Zealand to external shocks, as shown in figure 6. There was only a modest increase in the New Zealand and Finnish unemployment rates in the GFC despite rather severe economic downturns, especially in Finland – see figure 1 and figure 2. The economic shock in Finland in 1990 lead to high double-digit unemployment rates – see figure 6. The Finnish economy was able to absorb the global financial crisis with only a modest increase in unemployment – see figure 6.

Jan 12, 2015 @ 12:39:58

very interesting and excellent article. Finland got hit by the GFC harder as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people