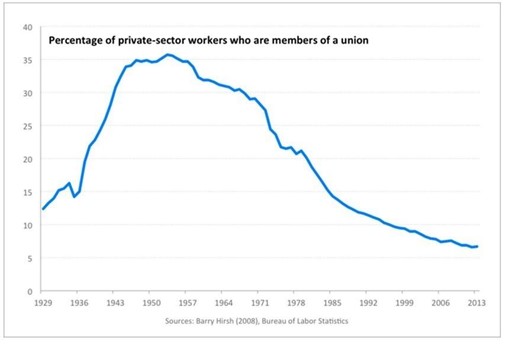

It is common to blame at least part of the increase in income inequality in the USA, at least, on the decline of unions. One factor put forward for that decline of unions is employers taking tough anti-union stands in certification elections and in the workplace on a day-to-day basis. Here is Paul Krugman’s views:

It’s often assumed that the U.S. labour movement died a natural death, that it was made obsolete by globalization and technological change. But what really happened is that beginning in the 1970s, corporate America, which had previously had a largely cooperative relationship with unions, in effect declared war on organized labour.

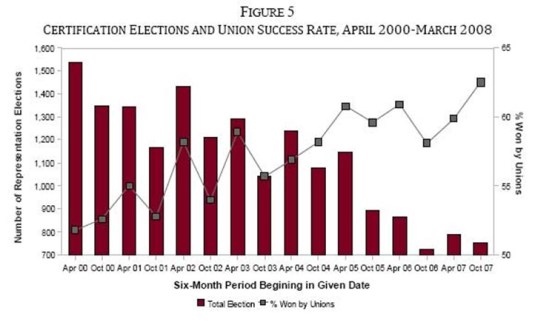

Certification elections in the USA are where workers vote to either join a union or leave it. If the union wins a certification election, all workers in that particular bargaining unit become members and the employer must bargain in good faith with the union about a collective agreement. A collective agreement is signed with the union after a certification election in about half of cases.

It is argued that this requirement for a certification election favours the employer in their anti-union struggle:

In the United States… secret-ballot election is held by the National Labor Relations Board, and usually only after a lengthy period in which employers can campaign against the union. “During the time between the petition and the election,” Warner writes, “which is often delayed by employer opposition and can last for months, employers usually run anti-union campaigns – often committing illegal acts of coercion, intimidation, or firing – in an attempt to discourage their employees from voting to unionize.” Research suggests (pdf) that U.S. employers have become remarkably adept in fending off unionization drives, often with the help of anti-union consultants.

In essence, this hypothesis about the decline of unions is a conspiracy theory, where the bosses are ganging up against the workers to entrench the inequality of bargaining power between employers and employees. Walmart is put forward as an employer who is known to strongly resist unions and fight union certification elections.

The flaw in that hypothesis of tough antiunion action by employers that have kept wages down is the nature of employment growth in the last 40 or 50 years in US manufacturing.

Rather than suffering setbacks in unionised workplaces, all the employment growth in the USA in manufacturing was in nonunionised workplaces. In an influential study, Farber and Western shows that:

…the decline of the union organization rate in the U.S. over the last three decades is due almost entirely to declining employment in union workplaces and rapid employment growth in non-union firms. Throughout the post-war period, new union organizing has never been the dominant determinant of the private sector union organization rate. Union organization has been most resilient when union firms could successfully retain employment in comparison to their non-union counterparts.

The productivity advantages of unionised firms are scant, according to Barry Hirsch. In the 1970s and 1980s, imports and new factories created new competition; airlines, trucking and communications (telephones) were deregulated in the USA, allowing new low-cost rivals into the market. Deregulation, privatisation and liberalisation of trade was common to in Australia, New Zealand, Britain, and a number of other countries.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KdOCWUgwiWs

Some argue that there are efficiency wage arguments. Unions raise morale and increase workers participation because there is less fear of management victimisation and arbitrary behaviour. Paul Krugman is a fine critic of this view:

They also argue that because there are cases in which companies paying above-market wages reap offsetting gains in the form of lower turnover and greater worker loyalty, raising minimum wages will lead to similar gains. The obvious economist’s reply is, if paying higher wages is such a good idea, why aren’t companies doing it voluntarily?

The essence of the efficiency wage argument for unions is employers don’t know how to make a profit. There are persistent, known but unexploited opportunities for profit from unionisation left on the table because of an undersupply of entrepreneurial alertness to untapped organisational and workplace innovations, and the resistance to unions is unprofitable to employers. Furthermore, nonunionised firms will not lose market share to firms that happen to be unionised and can undercut them in costs because of the windfall gains of the efficiency wage effects of unionisation.

A further complication for the union movement as the saviour of working class wages is careful study seems to have shown that the union wage premium in recent decades has been seriously overrated.

John DiNardo and David Lee compared business establishments from 1984 to 1999 where US unions barely won the union certification election (e. g., by one vote) with workplaces where the unions barely lost. If 50% plus 1 workers vote in favour of the union proposing to organise them, management has to bargain for a collective agreement in good faith with the certified union, if the union loses, management can ignore that union.

Most winning union certification elections resulted in the signing of a collective agreement not long after. Unions who barely win have as good a chance of securing a collective agreement as those unions that win these elections by wide margins.

Importantly, few firms subsequently bargained with a union that just lost the certification election. Employers can choose to recognise a union. Because the vote is so close, a particular workplace becoming unionised was close to a random event.

- This closeness of the union certification election may disentangle unionisation from just being coincident with well-paid workplaces, more skilled workers and well-paid industries.

- Unions could be organising at highly profitable firms that are more likely to grow and pay higher wages independent of any collective bargaining. The unions are possibly claiming credit for wage rises that would have happened anyway.

DiNardo and Lee found only small impacts of unionisation on all outcomes they examined:

- The estimated changes for wages of unionisation are close to zero.

- Impacts on survival rates of the unionised business and their profitability were equally tiny.

This evidence of DiNardo and Lee suggests that in recent decades in the USA, requiring an employer to bargain with a certified union has had little impact because unions have been unsuccessful in winning significant wage gains after unionisation. These findings by DiNardo and Lee suggests that there may not be a union wage premium at all since the early 1980s, at least in the USA.

In another paper DiNardo found a substantial union wage premium before the Second World War by studying the share price effects of unionisation. One of the differences back them that there was far more violence associated with strikes.

We find that strikes had large negative effects on industry stock valuation. In addition, longer strikes, violent strikes, strikes won by the union, strikes leading to union recognition, industry-wide strikes, and strikes that led to wage increases affected industry stock prices more negatively than strikes with other characteristics.

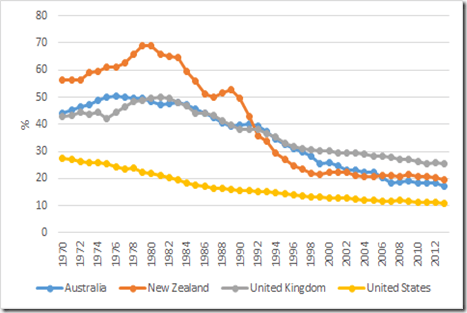

Private sector union membership is about 7% in the USA. Private sector union membership is barely in the teens in Australia and New Zealand. Fewer people are joining unions because they are not of any value to them. Union membership has been in a long slow decline in New Zealand since the mid-1970s.

Union density, New Zealand, Australia, the UK and USA 1970-2013

Source: OECD Stats Extract

There was no conspiracy. In an evolutionary process, non-union firms won market share from unionised firms, which is why there are fewer union members. Unionised workplaces contracted in size or closed. The more efficient firms, including those that are less unionised will not unionised will survive and prosper in competition against the more unionised firms in the same market.

Alchian in 1950 pointed out the evolutionary struggle for survival in the face of market competition ensured that only the profit maximising firms and ways of organising the business survived:

- Realised profits, not maximum profits, are the marks of success and viability in any market. It does not matter through what process of reasoning or motivation that business success is achieved.

- Realised profit is the criterion by which the market process selects survivors.

- Positive profits accrue to those who are better than their competitors, even if the participants are ignorant, intelligent, skilful, etc. These lesser rivals will exhaust their retained earnings and fail to attract further investor support.

- As in a race, the prize goes to the relatively fastest ‘even if all the competitors loaf.’

- The firms which quickly imitate more successful firms increase their chances of survival. The firms that fail to adapt, or do so slowly, risk a greater likelihood of failure.

- The relatively fastest in this evolutionary process of learning, adaptation and imitation will, in fact, be the profit maximisers and market selection will lead to the survival only of these profit maximising firms.

These surviving firms may not know why they are successful, but they have survived and will keep surviving until overtaken by a better rival. All business needs to know is a practice is successful. The reason for its success is less important.

One method of organising production and supplying to the market will supplant another when it can supply at a lower price (Marshall 1920, Stigler 1958). The more efficient sized firms are the firm sizes that are currently expanding their market shares in the face of competition; the less efficient sized firms are those that are currently losing market share (Stigler 1958; Alchian 1950; Demsetz 1973, 1976).

Business vitality and capacity for growth and innovation are only weakly related to cost conditions and often depends on many factors that are subtle and difficult to observe (Stigler 1958, 1987).

This subtle nature of business success can include the level of unionisation of the workforce. Without knowing it, the firms that are not unionised or are less unionised will slowly erode the market shares and profitability of the more unionised firms. This process will happen slowly through time as unions in that sector withers away.

The strength of the unions in the public sector and their withering away in the private sector may be the better place to look for an explanation of the decline of unions. Employers subject to a profit and loss constraint are less likely to survive if unionised. Public sector employers where union members have both union rights and voting rights are more likely to be favourable to the interests of unions.

Mar 18, 2015 @ 11:56:30

excellent article Jim,

Definitely in my Around the Traps so one more person will read this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mar 22, 2015 @ 07:44:11

Fantastic article. I agree that unions in the private sector basically bargain themselves out of jobs. The process though is slow and anything but assured. Absent higher productivity (which is a potential but certainly unlikely relative to higher wages) the higher costs have to go into either prices, lower quality, faster automation or lower profits. All of which lead over time to reduced market share and/or fewer union jobs

From the larger picture, unions are about those with union jobs forming a cartel against prospective employees. The framework of a class struggle is completely overblown and probably flat out disingenuous. The better framing is union workers against other workers.

LikeLiked by 1 person