Some argue that the Treaty of Union 1706 entrenches Scotland as a member of the United Kingdom now and forever. Lord Hope of Craighead put the question this way in the constitutional challenge to the law prohibiting foxhunting:

It has been suggested that some of the provisions of the Acts of Union of 1707 are so fundamental that they lie beyond Parliament’s power to legislate.

In 1706, England and Scotland were ruled by Anne as Queen in right of England and by Anne as Queen in right of Scotland respectively, and each with their own Parliaments. In 1706, Commissioners from each of the Parliaments negotiated Articles of Union, for a proposed union of England and Scotland into a Great Britain. The Scottish Parliament approved the Articles, with some amendments. The English Parliament legislated by the Union with Scotland Act 1706. The Union took effect on 1 May 1707.

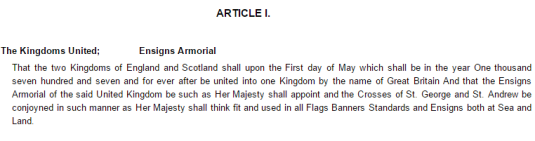

Article I provided for the two kingdoms to be united on 1 May 1707 “and forever after”, as Great Britain. The same Act of Union also secured the protestant succession at all times in the future, the continued existence of the Court of Session to “remain in all time coming within Scotland as it is now constituted by the laws of that Kingdom”, and provided for the establishment of the Church of Scotland to be “effectually and unalterably secured” and

This Act of Parliament with the Establishment therein contained shall be held and observed in all time coming as a fundamental and essential condition of any Treaty or Union to be concluded betwixt the two Kingdoms without any alteration thereof or derogation thereto in any sort for ever

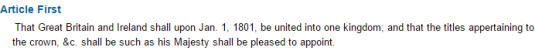

The union of the kingdoms of Great Britain and of Ireland in 1801, like the Anglo-Scottish union, was negotiated by commissioners and followed by Acts of the British and Irish Parliaments in 1800. They united both countries and contained entrenched provisions, for example, regarding the establishment of the Church of Ireland.

Despite that these ambition’s attempts at entrenchment and to limit the sovereignty of the new Parliament established in 1707, the United Kingdom Parliament has complete sovereignty to amend any provision of the Articles of the Acts of Union. Parliament is fully competent to amend or abrogate even an entrenched provision of the Articles. Judges at the highest level have accepted that Parliament enjoys complete legal sovereignty

Since 1707, the United Kingdom Parliament has legislated to abrogate provisions, including “entrenched” provisions, of both the Anglo-Scottish and the British-Irish Unions. Examples are the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1922, overriding of the entrenched provisions of the Acts of Union in relation to the establishment of the Church of Scotland and various piecemeal amendments.

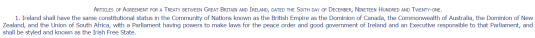

Most telling of all is the Irish Free State (agreement) Act 1922 and Irish Free State (Constitution) Act 1922. As the Royal Commission on the Constitution 1969-73, the Kilbrandon Commission, recognised as an ultimate example of the supremacy of Parliament:

No special procedures are required to enact even the most fundamental changes in the constitution. Thus the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 was made possible by an ordinary Act of Parliament, despite the declared intention of the Act of Union of 1800 that the union of Great Britain and Ireland should last for ever.

There is nothing to stop Parliament from granting Scottish independence, or indeed expelling Scotland from the UK. The British Parliament is sovereign – it can make or unmake any law whatsoever.

Parliamentary sovereignty is the defining principle of the United Kingdom’s constitution. It is ultimately for Parliament to decide what use to make of that power.

Parliament’s law-making power is not subject to any permanent restrictions, and therefore Parliament cannot bind its successors. As upheld in 2005 by Lord Bingham in the case of R (Jackson) v Attorney General:

The bedrock of the British Constitution is … the Supremacy of the Crown in Parliament… the Crown in Parliament was unconstrained by any entrenched or codified constitution. It could make or unmake any law it wished. Statutes, formally enacted as Acts of Parliament, properly interpreted, enjoyed the highest legal authority.

There is nothing new in this view with the British constitution. Lord Reid said in Pickin v British Railways Board [1974] HL:

The idea that a court is entitled to disregard a provision in an Act of Parliament on any ground must seem strange and startling to anyone with any knowledge of the history and law of our constitution

Likewise, Lord Reid again in 1969 in Madzimbamuto v. Lardner-Burke AC:

It is often said that it would be unconstitutional for the United Kingdom Parliament to do certain things, meaning that the moral, political and other reasons against doing them are so strong that most people would regard it as highly improper if Parliament did these things. But that does not mean that it is beyond the power of Parliament to do such things. If Parliament chose to do any of them the courts would not hold the Act of Parliament invalid.

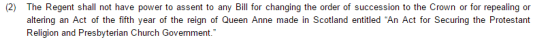

To end on the conundrum, the Regency Act 1937 limits the power of a Regent to give Royal assent to certain bills:

This way around parliamentary sovereignty by limiting the power of the sovereign to give Royal assent is handled in part by the Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act 1811. This dealt with the final madness of King George III.

The King was in no fit state to give Royal Assent. Parliament decided to have the Lord Chancellor approve the bill by fixing the Great Seal of the Realm to give Royal Assent. Such letters patent were irregular, because they did not bear the Royal Sign Manual, and only Letters Patent signed by the Sovereign can provide for the appointment of Lords Commissioners or for the granting of Royal Assent.

The enrolled bill doctrine of The King v Arundel (1616) and Edinburgh & Dalkeith Railway Co v Wauchope (1844) then applies:

All that a court of justice can do is to look at the Parliamentary Roll; if from that it should appear that a Bill has passed both Houses and received the Royal Assent, no court of justice can inquire into the mode in which it was introduced into Parliament, nor into what was done previous to its introduction, or what passed in Parliament during its progress in its various stages through both Houses.

Legal revolutions have a long history in British constitutional law, such as after the Glorious Revolution. The Crown and Parliament Recognition Act 1689 was an Act of the Parliament of England, passed in 1689. It confirmed both the succession to the throne of King William III and Queen Mary II of England and validity of the laws passed by the Convention Parliament which had been irregularly convened following the Glorious Revolution and the end of James II‘s reign.

Usurpations of the throne were not uncommon at that time. As a matter of State necessity a de facto King had been regarded as competent to summon a lawful Parliament. The succession of King James I, after Elizabeth I was itself a little irregular. Arabella Stuart, Queen Elizabeth’s her first cousin twice removed, had a strong hereditary claim.

Recent Comments