The quickening in creative destruction and CEO turnover

03 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in financial economics, labour economics, managerial economics, market efficiency Tags: CEO turnover, creative destruction

A market in which prices always fully reflect available information is called efficient

27 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in experimental economics, financial economics, market efficiency Tags: efficient markets hypothesis

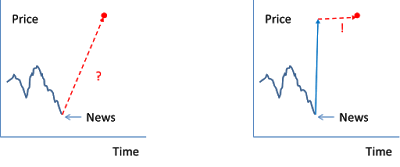

Source: John Cochrane

A share market that jumps suddenly when there is news of change in economic corporate fortunes is efficient.

This means that an efficient market can be highly volatile because it is rapidly incorporating changes in information. An efficient market is a volatile market.

As for smart money managers beating an efficient market, John Cochrane explains:

…efficiency implies that trading rules — “buy when the market went up yesterday”– should not work.

The surprising result is that, when examined scientifically, trading rules, technical systems, market newsletters, and so on have essentially no power beyond that of luck to forecast stock prices.

This is not a theorem, an axiom, a philosophy, or a religion: it is an empirical prediction that could easily have come out the other way, and sometimes does.

Efficiency implies that professional managers should do no better than monkeys with darts. This prediction too bears out in the data.

It too could have come out the other way. It should have come out the other way! In any other field of human endeavour, seasoned professionals systematically outperform amateurs. But other fields are not as ruthlessly competitive as financial markets.

Crony capitalism flashback – who voted against the TARP in 2008?

20 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, rentseeking Tags: crony capitalism, TARP

The US House of Representatives initially voted down the TARP in a grand coalition of right-wing republicans and left-wing democrats, voting 205–228. The right-wing republicans opposed the bailout because capitalism is a profit AND loss system. Democrats voted 140–95 in favour of the Bill while Republicans voted 133–65 against it.

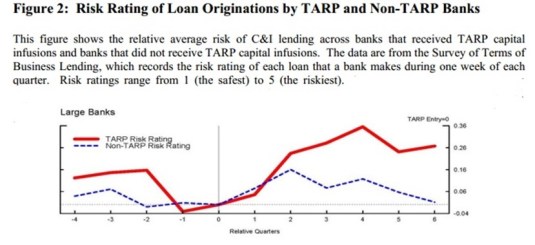

The chart above shows that the degree of risk in commercial loans made by TARP recipients appears to have increased. This is no surprise. In the 1960s, Sam Peltzman published a paper in in the 1960s showing that when deposit insurance was introduced in the USA in the 1930s, the banks halve their capital ratios. They did not need to have as much capital as before to back their lending. The chart below shows that the TARP really didn’t do much for economic policy uncertainty.

In an open letter sent to Congress, over 100 university economists described three fatal pitfalls in the TARP:

1) Its fairness. The plan is a subsidy to investors at taxpayers’ expense. Investors who took risks to earn profits must also bear the losses. The government can ensure a well-functioning financial industry without bailing out particular investors and institutions whose choices proved unwise.

2) Its ambiguity. Neither the mission of the new agency nor its oversight is clear. If taxpayers are to buy illiquid and opaque assets from troubled sellers, the terms, timing and methods of such purchases must be crystal clear ahead of time and carefully monitored afterwards.

3) Its long-term effects. If the plan is enacted, its effects will be with us for a generation. For all their recent troubles, America’s dynamic and innovative private capital markets have brought the nation unparalleled prosperity. Fundamentally weakening those markets in order to calm short-run disruptions is will short-sighted.

A recent IMF study of 42 systemic banking crises showed that in 32 cases, there was government financial intervention.

Of these 32 cases where the government recapitalised the banking system, only seven included a programme of purchase of bad assets/loans (like the one proposed by the US Treasury). These countries were Mexico, Japan, Bolivia, Czech Republic, Jamaica, Malaysia, and Paraguay.

The Government purchase of bad assets was the exception rather than the rule in banking crises and rightly so. The TARP mostly benefited bank shareholders. A case of privatising the gains and socialising the losses from banking was passed on the votes of Congressional Democrats.

The share market speaks on renewable energy

19 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, energy economics, financial economics Tags: Bjørn Lomborg, event studies, renewable energy

To avert a financial panic, central banks should lend early and freely to solvent banks against good collateral but at penal rates

19 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, Thomas M. Humphrey Tags: lender of last resort, Thomas Humphrey, Walter Bagehot

First. That these loans should only be made at a very high rate of interest. This will operate as a heavy fine on unreasonable timidity, and will prevent the greatest number of applications by persons who do not require it. The rate should be raised early in the panic, so that the fine may be paid early; that no one may borrow out of idle precaution without paying well for it; that the Banking reserve may be protected as far as possible.

Secondly. That at this rate these advances should be made on all good banking securities, and as largely as the public ask for them. The reason is plain. The object is to stay alarm, and nothing therefore should be done to cause alarm. But the way to cause alarm is to refuse some one who has good security to offer… No advances indeed need be made by which the Bank will ultimately lose. The amount of bad business in commercial countries is an infinitesimally small fraction of the whole business…

The great majority, the majority to be protected, are the ‘sound’ people, the people who have good security to offer. If it is known that the Bank of England is freely advancing on what in ordinary times is reckoned a good security—on what is then commonly pledged and easily convertible—the alarm of the solvent merchants and bankers will be stayed. But if securities, really good and usually convertible, are refused by the Bank, the alarm will not abate, the other loans made will fail in obtaining their end, and the panic will become worse and worse.

Walter Bagehot Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873).

The classical theory of the lender of last resort stressed

(1) protecting the aggregate money stock, not individual institutions,

(2) letting insolvent institutions fail,

(3) accommodating sound but temporarily illiquid institutions only,

(4) charging penalty rates,

(5) requiring good collateral, and

(6) preannouncing these conditions in advance of crises so as to remove uncertainty.

Did anyone follow these rules in the global financial crisis? The Fed violated the classical model in at least seven ways:

- Emphasis on Credit (Loans) as Opposed to Money

- Taking Junk Collateral

- Charging Subsidy Rates

- Rescuing Insolvent Firms Too Big and Interconnected to Fail

- Extension of Loan Repayment Deadlines

- No Pre-announced Commitment

- No Clear Exit Strategy

…{the Fed’s} policies are hardly benign, and that extension of central bank assistance to insolvent too-big-to-fail firms at below-market rates on junk-bond collateral may, besides the uncertainty, inefficiency, and moral hazard it generates, bring losses to the Fed and the taxpayer, all without compensating benefits. Worse still, it is a probable prelude to a severe inflation and to future crises dwarfing the current one.

Why governments cannot pick winners

11 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, entrepreneurship, financial economics Tags: efficient market hypothesis, hedge fund managers, picking winners, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

|

The salary of one top hedge fund manager exceeds the entire payroll of any of the government departments in New Zealand. To get on the list of top 25 hedge fund manager you must earn at least $300 million a year. The best of these earned $3 billion last year. Anyone who was any good at picking the share market would certainly not accept government wages. Government employees have neither the aptitude nor the taste for risk that betting it all every day and losing everything perhaps requires. |

The share market as a spy, investigator and muckraker: using share price movements to uncover secrets and solve mysteries

23 May 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, financial economics, industrial organisation, survivor principle Tags: Armen Alchian, event studies

Armen Alchian successfully identifying lithium as the fissile fuel in the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb using only publicly available financial data. The early 1954 RAND corporation memo by Alchian was classified a few days later.

The Stock Market Speaks: How Dr. Alchian Learned to Build the Bomb by Joseph Michael Newhard, August 27, 2013 at for a replication study of Alchian’s event study of share market reactions to the Bikini Atoll nuclear detonations in 1954 updated with declassified information and modern finance theory.

An extra challenge for Alchian was not only was the component of the bomb classified, whether the explosion was atomic or hydrogen was classified too.

The share price of the supplier of lithium surged within a few days.

The replication study by Newhard found a significant upward movement in the price of Lithium Corporation relative to the other corporations. Within three weeks of the explosion, its shares were up 48% before settling down to a monthly return of 28% despite secrecy, scientific uncertainty, and public confusion surrounding the test; the company saw a return of 461% for the year.

The share market is a surprising efficient tool for discerning new knowledge.

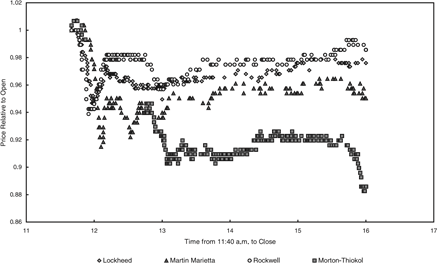

After the Challenger space shuttle disaster in 1986, the share market identified within the hour which component supplier made the faulty part and marked it down accurately as to damages and loss of business. The blue ribbon commission of inquiry took 6-months to find the culprit.

In the period immediately following the crash, securities trading in the four main shuttle contractors singled out Morton Thiokol as having manufactured the faulty component.

Intraday stock price movements following the challenger disaster

At market close, Thiokol’s shares were down nearly 12 per cent. By contrast, the share prices of the three other firms started to creep back up, and by the end of the day their value had fallen only around 3 per cent.

Morton Thiokol shed some $200 million in market value on the day. Over the next several months, the other contractors recovered and outperformed the market while Morton Thiokol lagged.

As a result of the investigation, Morton Thiokol had to pay legal settlements and perform repair work of $409 million at no profit. It also dropped out of bidding for future business.

The $200 million equity decline for Morton Thiokol in hindsight is a reasonable prediction of lost cash flows that came as a result of the judgment of culpability in the crash.

William Brown found that a group of firms that had significant ties to Lyndon Johnson increased in the market value after President Kennedy’s assassination. The share prices of General Dynamics, whose main aircraft plant was located in Fort Worth, Texas, climbed from $23.75 on November 22 to $25.13 on November 26, and by February 1964 was up over $30, a jump of around 30 per cent in three months.

Over the ten trading days following the announcement of Timothy Geithner’s nomination as U.S. Treasury Secretary, financial firms with a connection to Geithner experienced a cumulative abnormal return of about 12% relative to other financial sector firms. This reversed when his nomination ran into trouble due to unexpected tax return issues.

Pat Akey (2013) looked at the abnormal returns in share prices around close U.S. congressional elections. Firms gain on the election of a politician with whom they are connected – and they lost when he or she is defeated. The cumulative abnormal return to be between 1.7% and 6%.

Recent Comments