Thomas Sowell (former Marxist) Dismantles Leftist Ideology

01 Dec 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, comparative institutional analysis, history of economic thought, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: Thomas Sowell

Deirdre McCloskey on the origins of the #minimumwage

01 Dec 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, history of economic thought, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: Deirdre McCloskey, eugenics, Leftover Left, New Left, Old Left

Source: Liberalism, Neoliberalism, and the Literary Left Interview by W. Stockton and D. Gilson (forthcoming).

Skill-specific atrophy rates drive the STEM gender gap

08 Nov 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of education, gender, human capital, labour economics, minimum wage, occupational choice Tags: gender wage gap, reversing gender gap

Rendall and Rendall (2016) found that women prefer occupations where their skills depreciate slowest when taking time out from motherhood. Verbal and reading skills depreciate at a far slower rate than mathematical and scientific skills so this gives women yet another strong reason to avoid science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) careers.

we show that college educated women avoid occupations requiring significant math skills due to the costly skill atrophy experienced during a career break. In contrast, verbal skills are very robust to career interruptions.

The results support the broadly observed female preference for occupations primarily requiring verbal skills – even though these occupations exhibit lower average wages. Thus, skill-specific atrophy during employment leave and the speed of skill repair upon returning to the labour market are shown to be important factors underpinning women’s occupational outcomes.

Not only do women have vastly superior verbal and reading skills, worth somewhere near 6 to 12 months extra schooling, these skills do not depreciate much during career breaks. Indeed, reading and verbal skills tend to naturally increase with age until your late 60s.

Source: Reading performance (PISA) – International student assessment (PISA) – OECD iLibrary.

Maths skills get rusty if not used while knowledge of computer languages and the like and of specific technologies can be quickly overtaken by events while on maternity leave. Rendall and Rendall (2016) again

… college educated females avoid math-heavy occupations, and pursue verbal-heavy occupations instead. This is due to the high skill atrophy associated with math skills, and the ability of verbal skills to act as “skill insurance” against gaps.

Additionally, for college educated individuals, math is the skill most vulnerable to loss during employment gaps, which also implies a slow rebuilding post-break. In contrast, non-college educated individuals experience a much smaller math skill loss.

Rendall and Rendall’s point about college educated women avoiding maths heavy occupations even if it costs them wages so as to maximise the lifetime income may explain the larger gender wage gap at the top of the income distribution than at the bottom.

At the bottom of the income distribution, skill atrophy do not really matter much. At the top, it do. Women make occupational choices where annual income may be lower but lifetime income may be higher because of the lower rates of skill depreciation when they are out having children.

Glenn Loury and David Neumark on the minimum wage – Bloggingheads.tv

15 Oct 2016 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage Tags: David Neumark

What economists know about the minimum wage 6:57

Is Paul Krugman dead wrong about the minimum wage? 3:32

Measuring the disemployment effect 6:43

David’s critique of a famous pro–minimum wage study 12:50

Do workers earn what they’re worth? 6:47

David: Target aid to low-income families, not low-wage workers 7:56

Arin Dube: The impact of a minimum wage

14 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage

Does it Feel Good or Does it Do Good?

08 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics, labour economics, minimum wage, Public Choice Tags: expressive voting, rational irrationality

@ALeighMP, Lindsay Mitchell v. Susan St. John on family tax credit incidence

19 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand

There is some feuding in the letters to editor page of the Sunday Star Times today between Lindsay Mitchell and Susan St John about whether employers pocket some of the Working for Families tax credit by reducing the wages they offer.

I have contracted-out my reply on the economic incidence of in-work tax credits to a former ANU economics professor who is now an Australian Labour Party federal MP.

There is general agreement such as summarised by the Economist that a significant part of family tax credits goes into the pockets of employers:

An analysis of the EITC published in 2010 by Andrew Leigh of the Australian National University found that most of the benefit of the credit went to workers. Not all of it did though: a 10% increase in the credit was associated with a 5% dip in wages of high-school dropouts. By the same token, a study conducted the following year by Mr Rothstein found that for each dollar spent on tax credits, existing workers’ income rose by $0.73 (although $0.09 of this was because they chose to work more). Employers gained $0.36, as they spent less on wages.

Economists at Britain’s National Institute of Economic and Social Research are conducting a similar study of the British system of tax credits. Childless workers become eligible for the credits at the age of 25. By comparing wages either side of this threshold, they have been able to estimate how much the credits are depressing wages. Their preliminary (and unpublished) results suggest that, of the 76p an hour the government forks out in tax credits for someone on the minimum wage, 72-79% goes to workers.

In work tax credits increases labour supply, which depresses wages except where wages are pressing up against a binding minimum wage. Steve Landsberg has pointed out a paradoxe of a binding minimum wage when there is an earned income tax credit:

If you increase the EITC in a market with an effective minimum wage, you’ll get a whole lot more workers competing for the same limited number of jobs, and this competition must continue until all of the benefits have either been dissipated or transferred to employers, who are now able to demand harder work and offer fewer perquisites.

Does @nztreasury @moturesearch understand its own 90-day trials research?

17 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, econometerics, economics of regulation, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - New Zealand Tags: employment law, employment protection law, employment regulation, offsetting behaviour, probationary periods, trial periods

https://twitter.com/moturesearch/status/743595301345333248

Media reporting and Motu’s own tweet on its research contradict its own conclusions about what it found about the introduction of 90-day trial periods for new jobs in New Zealand.

https://twitter.com/moturesearch/status/743563189451841537

Motu’s executive summary is both as bold as the Motu tweet and directly contradicts it

We find no evidence that the ability to use trial periods significantly increases firms’ overall hiring; we estimate the policy effect to be a statistically and economically insignificant 0.8 percent increase in hiring on average across all industries.

However, within the construction and wholesale trade industries, which report high use of trial periods, we estimate a weakly significant 10.3 percent increase in hiring as a result of the policy.

No evidence means no evidence. Not no evidence but we did find some evidence in two large industries – evidence of a 10.3% increase in hiring. That is a large effect.

Both economic and statistical significance matter. Not only is the effect of 90-day trial periods in the construction and wholesale trades other than zero, 10% is large – a hiring boom. No evidence of any effects on employment of 90 day trial periods means no evidence.

Neither Treasury nor Motu understand their own research and the evidence of large effects in two industries. Can you conclude you have no evidence when you have some evidence, which they did in construction and wholesale trades? There is evidence, there is not no evidence.

The paper was weak in hypothesis development and in its literature review. It was not clear whether the paper was testing the political hypothesis or the economic hypotheses. Neither were well explained or situated within modern labour economics or labour macroeconomics. If a political hypothesis does not stand up as a question of applied price theory, you cannot test it.

The Motu paper does not remind that graduate textbooks in labour economics show that a wide range of studies have found the predicted negative effects of employment law protections on employment and wages and on investment and the establishment and growth of businesses:

1. Employment law protections make it more costly to both hire and fire workers.

2. The rigour of employment law has no great effect on the rate of unemployment. That being the case, stronger employment laws do not affect unemployment by much.

3. What is very clear is that is more rigourous employment law protections increase the duration of unemployment spells. With fewer people being hired, it takes longer to find a new job.

4. Stronger employment law protections also reduce the number of young people and older workers working age who hold a job.

5. The people who suffer the most from strong employment laws are young people, women and older adults. They are outside looking in on a privileged subsection of insiders in the workforce who have stable, long-term jobs and who change jobs infrequently.

Trial periods are common in OECD countries. There is plenty of evidence that increased job security leads to less employee effort and more absenteeism. Some examples are:

- Sick leave spiking straight after probation periods ended;

- Teacher absenteeism increasing after getting tenure after 5-years; and

- Academic productivity declining after winning tenure.

Jacob (2013) found that the ability to dismiss teachers on probation – those with less than five years’ experience – reduced teacher absences by 10% and reduced frequent absences by 25%.

Studies also show that where workers are recruited on a trial, employers have to pay higher wages. For example, teachers that are employed with less job security, or with longer trial periods are paid more than teachers that quickly secure tenure.

Workers who start on a trial tend to be more productive and quit less often. The reason is that there was a better job match. Workers do not apply for jobs to which they think they will be less suited. By applying for jobs that the worker thinks they will be a better fit, everyone gains in terms of wages, job security and productivity. For more information see

- Pierre Cahuc and André Zylberberg, The Natural Survival of Work, MIT Press, 2009;

- Tito Boeri and Jan van Ours, The Economics of Imperfect Labor Markets, MIT Press, 2nd edition (2013);

- Dale T. Mortensen, “Markets with Search Friction and the DMP Model”, American Economic Review 101, no. 4 (June 2011): 1073-91;

- Christopher Pissarides. “Equilibrium in the Labor Market with Search Frictions”, American Economic Review 101 (June 2011) 1092-1105;

- Christopher Pissarides, “Employment Protection”, Labour Economics 8 (2001) 131-159.

- Eric Brunner and Jennifer Imazeki, “Probation Length and Teachers Salaries: Does Waiting Payoff?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64, no. 1 (October 2010): 164-179.

- Andrea Ichino and Regina T. Riphahn, “The Effect of Employment Protection on Worker Effort – A Comparison of Absenteeism During and After Probation”, Journal of the European Economic Association 3 no. 1 (March 2005), 120-143;

- Christian Pfeifer “Work Effort During and After Employment Probation: Evidence from German Personnel Data”, Journal of Economics and Statistics (February 2010); and

- Olsson, Martin “Employment protection and sickness absence”, Labour Economics 16 (April 2009): 208-214.

In the labour market, screening and signalling take the form of probationary periods, promotion ladders, promotion tournaments, incentive pay and the back loading of pay in the form of pension vesting and other prizes and bonds for good performance over a long period.

There is good reasons to have strong priors about how employment regulation will work. Employment law protects a limited segment of the workforce against the risk of losing their job. These are those who have a job and in particular those that have a steady job, a long-term job.

The impact of the introduction of trial periods on employment will be ambiguous because the lack of a trial period can be undone by wage bargaining.

- If you have to hire a worker with full legal protections against dismissal, you pay them less because the employer is taking on more of the risk if the job match goes wrong. If they work out, you promote them and pay them more.

- If you hire a worker on a trial period, they may seek a higher wage to compensate for taking on more of the risks if the job match goes wrong and there is no requirement to work it out rather than just sack them.

The twist in the tail is whether there is a binding minimum wage. If there is a binding minimum wage, either the legal minimum or in a collective bargaining agreement, the employer cannot reduce the wage offer to offset the hiring risk so fewer are hired.

The introduction of trial periods will affect both wages and employment and employment more in industries that are low pay or often pay the minimum wage. Motu found large effects on hiring in two industries that used trial periods frequently. That vindicates the supporters of the law.

Motu said that 36% of employers have used trial periods at least once. The average is 36% of employers have used them with up to 50% using them in construction and wholesale trade. That the practice survives in competition for recruits suggested that it has some efficiency value.

The large size of the employment effect in construction and wholesale trades is indeed a little bit surprising. Given that a well-grounded in economic theory hypothesis about the effect of trial period is ambiguous in regard to what will happen to wages and unemployment, a large employment effect is a surprise. If Motu had spent more time explaining employment protection laws and what hypotheses they imply, that surprise would have come to light sooner.

Motu’s research for the remaining New Zealand industries was a bit of an outlier. It should have spent more time explaining how to manage that anomalous status in light of the strong priors impartial spectators are entitled to have on the economics of employment protection laws.

A conflicting study about the effects of any regulation should be no surprise. If there are not conflicting empirical studies, the academics are not working hard enough to win tenure and promotion. Extraordinary claims nonetheless require extraordinary evidence.

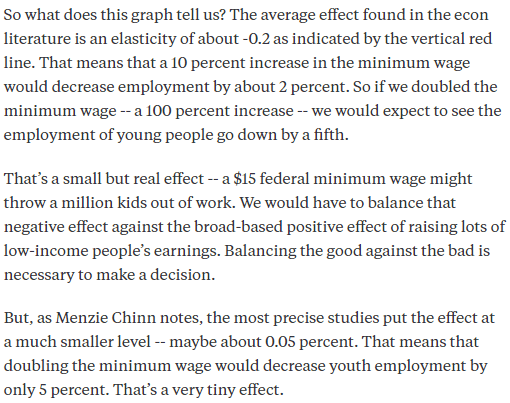

@Noahpinion says 20% losing their jobs is a small price to pay in #fightfor15

14 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage, Robert E. Lucas

https://twitter.com/EconBizFin/status/626687442834300928

Noah Smith is a type of friend that should make poor Americans prefer their republican enemies. At least they are not fanatics. Fanatics never give up. Evil people have other things to do with their dastardly days.

Source: A Higher Minimum Wage Won’t Lead to Armageddon – Bloomberg View.

Describing 1/5th of young people losing their jobs after a doubling of the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour as a small but real effect is a type of callousness that not even Donald Trump could stoop. What is Even Noah Smith admits that large minimum wage increases experiment with the fortunes of young people

We don’t really know what happens when you raise the minimum wage to $15 — but soon, we will know. We will be able to see whether employment rates fall in L.A., Seattle, and San Francisco.

We will be able to see whether people who can’t get work migrate from these cities to cities with lower minimum wages. We will be able to see if employment growth suddenly slows after the enactment of the policy. In other words, federalism will do its job, by allowing cities to act as policy laboratories for the rest of the country.

These one million young people who may well lose their jobs under a $15 minimum wage are real living people starting out their work in lives in a country with a rather inadequate unemployment benefits especially for the long-term unemployed.

Noah Smith wants to throw them onto the scrapheap through a large increase in the minimum wage because he is too cheap to support a large increase in the earned income tax credit.

If doubling the minimum wage to throw 20% of the workforce out of a job passes the brutal utilitarian calculus of bleeding-heart progressives, why not double everybody’s wages? Show the strength of your conviction about these Kruger–Card minimum wage results which repeal the laws of supply and demand.

https://twitter.com/AlvaroLaParra/status/738776906988822528

The leading reason for empirical research and economic history is to warns us not to repeat the mistakes of the past and not try experiments that are obvious folly. People and the economy should not be used as lab rats as Lucas explains in his short speech “What Economists Do”

I want to understand the connection between the money supply and economic depressions.

One way to demonstrate that I understand this connection–I think the only really convincing way–would be for me to engineer a depression in the United States by manipulating the U.S. money supply.

I think I know how to do this, though I’m not absolutely sure, but a real virtue of the democratic system is that we do not look kindly on people who want to use our lives as a laboratory. So I will try to make my depression somewhere else.

#feelthebern will raise your taxes

09 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics, entrepreneurship, health economics, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA, public economics Tags: 2016 presidential election, antimarket bias, expressive voting, living wage, Old Left, pessimism bias, rational irrationality

Did #FightFor15 forget that @FightFor15 was an ambit claim for a #livingwage

07 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, comparative institutional analysis, labour economics, minimum wage, politics - USA, Public Choice Tags: antimarket bias, expressive voting, living wage, rational rationality

Any decent political movement makes an ambit claim in expectation of being beaten back to its real position. That is basic negotiation tactics in politics.

Such is the volatility of expressive politics that the fight for 15 campaign has taken on a life of its own and is actually delivering on a $15 living wage as the minimum wage in the USA in a growing number of states and cities as well is in Democratic party presidential campaign pledges.

If there is any degree of economic sanity and practicality among living wage advocates, they know that such a high living wage increase will cost jobs.

After all, if a large wage increase for low-paid workers cost no jobs, why not increase everyone’s wage by a similar percentage, which is about 100% in the USA?

#MiltonFriedman v. @berniesanders

05 Jun 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, development economics, economic history, economics, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, growth disasters, growth miracles, income redistribution, industrial organisation, labour economics, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, minimum wage, occupational choice, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics Tags: 2016 presidential election, Leftover Left

Recent Comments