Sam Peltzman on Teacher’s Unions

15 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of education, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, unions Tags: School choice, teachers unions, union power, union wage premium

The Unappreciated Success Of Charter Schools

10 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of education, Public Choice, rentseeking, unions Tags: charter schools, School choice

Union density has taken a bit of a battering in US manufacturing and construction

05 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

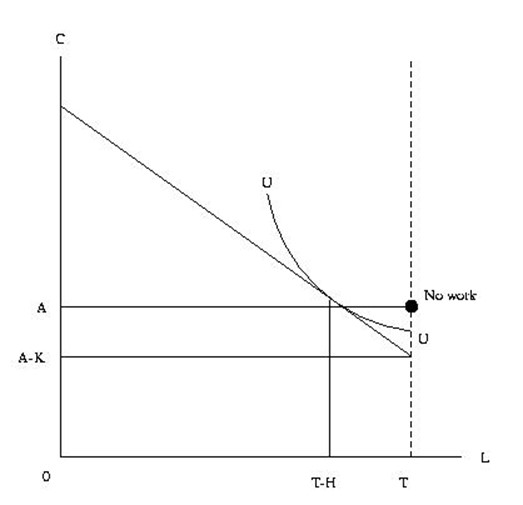

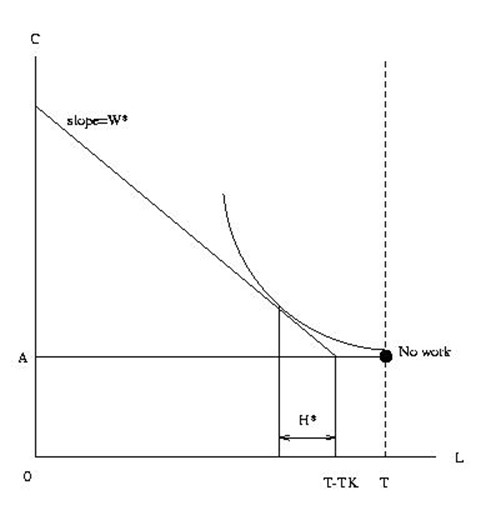

Some economics of zero hours contracts – part 4: team production as a constraint on working time flexibility

07 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, managerial economics, organisational economics, personnel economics, unions Tags: labour economics, zero hours contracts

To continue with my theme in my previous three blogs that zero hours contracts aren’t supposed to exist, a leading explanation for the hesitancy of employers to agree to part-time hours is team production (Hutchens and Grace-Martin 2004, 2006; Hutchens 2010).

Employers may want their employees to work a minimum number of working hours because of rigid production technologies and/or team production. Production technologies vary in the rigidity they impose on the hours worked by employees.

The co-ordination of working times is paramount to effective team production. Once the work time schedule is fixed for team, the worker faces a choice between working at the fixed schedule or working in another team or job.

Two common examples of teams are an assembly line and a football team. Both require a minimum number of workers with rigid starting and finishing times. The absence of a team member could reduce team productivity or safety or even stop production entirely.

When the cost of absence is higher such as for team production, there are more efforts to reduce absences. When a single employee absence is costly to employers, employers take steps to ensure that a minimum number of workers plus a reserve are present. There will be increased spending on monitoring, more cross-training, mutual monitoring by employees and the use of peer pressure. Multiple production lines reduce the risks of absence because spare staff can be hired to fill in across different teams.

Other workers can produce independently of their co-workers. One example is a member of a typing pool. The contribution of each typist depends on their efforts alone. The increment they add to production does not vary with the presence or absence of others, nor is the productivity of others affected by their output. If there is little teamwork, the absence of a worker does not affect other workers.

The Department of Labour (2009) found that about 60 per cent of New Zealand full-time employees did not have flexible hours.

A leading reason for employers hiring part-time workers is to solve scheduling problems that arise when hours of operation and peak periods of daily or weekly production do not easily divide into standard shift lengths.

For example, within the day and within the week variation in customer demand explains the heavy use of part-timers in restaurants, retails stores and many services outlets. Not surprisingly, zero hours contracts arise in industries such as the food services sector where there is already a long history of part-time work.

Different production technologies require their own levels of coordination and supervision. This complicates the use of part-timers. Scheduling problems can arise of workers arrive at different times.

A mix of full and part-time employees could increase supervision costs. There can be repetitions of instructions and different capabilities to perform the same tasks.

Two part-timers could be productive if job is repetitive and does not require much co-ordination. Again, and not surprisingly, zero hours contracts occur in industries where the jobs appear to be relatively simple and the worker can pretty much work out what to do after a little bit of training with little supervision.

A managerial employee is less likely to be allowed to be part-time because they will be absent when employees need direction (Hutchens and Grace-Martin 2004, 2006. Managerial employees have scale effects. Higher level management decisions percolate through the rest of the organisation. The interaction of talent and scale ensures that the impact of any loss of efficiency from having part-time managers compound geometrically into the efforts and productivity of those they lead. Sharing a managerial job has costs because information must be exchanged and a common agenda agreed.

The economics of team production suggests that zero hours contracts will occur in teams with peaks and ebbs in customer demand, where workers are pretty much interchangeable alone can take over with little or no instructional briefing, and the level of task dependency between workers is small.

When extra workers on zero hours contracts are brought on to deal with the spike in demand, they take over the servicing of this demand. There is little need for them to interact with existing workers. For example, in a restaurant situation, they could deal with the extra tables filled by the spike in demand. In a McDonald’s restaurant, for example, they could just take over that the till that was otherwise not in use and serve the extra queues of customers.

To summarise, unless we have a good idea about why firms are moving to zero hours contracts, which we don’t, and why employees sign these contracts rather than work for other employers who offer more regular hours of work, meddling in these still novel arrangements is pretty risky.

The Best Minimum Wage Story Of The Day, Or, Yes, Wage Rises Really Do Kill Jobs

30 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, minimum wage, unemployment, unions Tags: living wage, minimum wage

Trends in union membership in New Zealand, Australia, the UK and the USA

27 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in labour economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, unions Tags: Employment Contracts Act, union membership

The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand says that the rate of union membership dropped sharply to under 20% when the Employment Contracts Act was passed in 1991 using the chart below.

Figure 1: Percentage of union members

The OECD union density data, which allows international comparisons back to 1970, tells a different story. OECD data on union membership in New Zealand started in 1970.

Figure 2: Union density,New Zealand, Australia, the UK and USA 1970-2013

Source: OECD Stats Extract

Note: Trade union density corresponds to the ratio of wage and salary earners that are trade union members, divided by the total number of wage and salary earners (OECD Labour Force Statistics).

Figure 2 above shows that union membership has been in a long slow decline in New Zealand since the mid-1970s. This is been pretty much the pattern all round the world.

The much hated Employment Contracts Act 1991, much hated by the Left over Left, doesn’t really show up in the union density figures in figure 2. There is no sudden break in trend obvious in figure 2.

The longer time series in union membership in figure 1 compiled by the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand has long gaps between the data observations. Because of this, the sharp decline in union membership from the late 1970s, which it actually show up in its start-up , is not sufficiently distinguished from subsequent events because of the long gaps between observations reported in the figure 1.

If anything, union membership stopped declining in New Zealand in the late 1990s. Stabilising at about 20% of wage and salary earners.

Union membership continued to decline slowly in Australia, the UK and the USA subsequent to 1998. Union membership stabilised in New Zealand by contrast. Perhaps the Employment Contracts act should be able to claim credit for that?

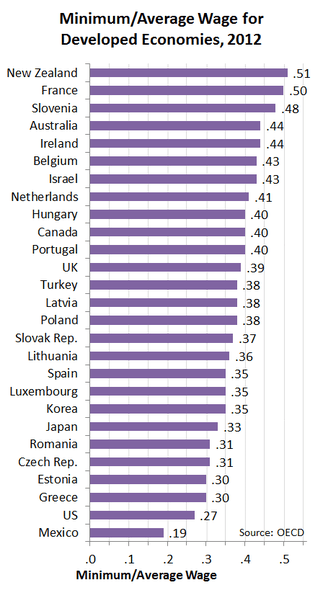

Minimum wage coverage in Europe

24 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in economics, labour economics, minimum wage, unions Tags: median voter, minimum wage, unions

Germany, Denmark, Italy, Austria, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland do not have a statutory minimum wage. Capitalist hell-holes all.

A common feature of this group of countries is the high coverage rate of union agreed minimum wages, generally laid down in sectoral agreements by employers associations with unions.

The percentage of employees covered by union agreed minimum wages ranges from approximately 70% in Germany and Norway to almost 100% in Austria and Italy (though excluding irregular workers, who make up a relatively large share of the Italian labour market). Italy has a huge underground economy.

In Denmark, the percentage of employees covered by union agreed wages is estimated at between 81% and 90%, while in Finland and Sweden, this figure is 90%.

Scandinavia is a capitalist hell-hole that every true blue social democrat must denounce without reservation. Their so called left-wing parties as traitors to the working class and to the least powerful of all workers – the low-paid and unskilled.

The poor should not have to rely on scraps from the tables of the middle-class unions. They have been deserted by their so called social democratic governments.

Whether the low-paid and low-skilled get a fair consideration from unions in collective bargaining given these unions will be driven by majority rule – by the median voter/union member who is older, senior and of high job tenure – is a question worth exploring.

The evidence is not good. In the Finnish depression in the early 1990s, the unions refused to agree to nominal wage cuts despite 20% unemployment – the worst since the 1930s. They protect those that still had a job.

Most European labour markets are dual labour markets. Unions and employment protection laws ensure that they are made up of two-tier systems with ultra-secure permanent jobs with the rest on temporary contracts.

Recent Comments