The regulatory impact statement on the employment law amendments by the new government says that:

The bill aims to strengthen collective bargaining through a range of measures, including guaranteed rest and meal breaks, reasonable union access to a workplace, and bringing back the 30-day rule where a new worker must be given the same conditions as a collective agreement.

MBIE officials found that the cost of the proposals would mainly fall on employers, including from higher wages and compliance costs, and from a potential fall in productivity.

The MBIE papers identified the following risks associated with the bill:

• reduced employment due to changed incentives on employers to hire new workers • an increase in industrial action and protracted bargaining due to the need to conclude agreements and include pay rates in collective agreements

• an increase in partial strikes by removing an employer’s ability to deduct pay for partial striking

• lower productivity due to less flexibility (mainly from the need for guaranteed meal breaks)

These predictions ignore the main findings of labour macroeconomics on employment protection laws and of empirical labour economics regarding the power of unions and the size of the union wage premium in the private sector.

What do employment protection laws do?

Let us begin with what are the standard predictions of the effect of employment protection laws. They lower wages and have an ambiguous effect on employment because there is both less hiring and less firing. The only unambiguous effect is on the duration of unemployment because fewer vacancies are posted but once you get a job, you keep it for longer. The unemployed must remain unemployed longer because their own fewer job vacancies posted. They must wait longer for a new vacancy suitable to their background and skills to open.

To give a summary of the literature that appears to be unknown to the junior analyst writing the Regulatory Impact Statement from this Bill, graduate textbooks in labour economics show that a wide range of studies have found that:

1. Employment law protections make it costlier to both hire and fire workers.

2. The rigour of employment law has no great effect on the rate of unemployment. That being the case, stronger employment laws do not affect unemployment by much.

3. What is clear is that is more rigorous employment law protections increase the duration of unemployment spells. With fewer people hired, it takes longer to find a new job.

4. Stronger employment law protections also reduce the number of young people and older workers who hold a job. They are outside looking in on a privileged subsection of insiders in the workforce who have stable, long-term jobs and who change jobs infrequently.

When trying to work out what the effects of the effects of this Bill on the labour market, the key consideration is the extent to which wage bargaining can undo most if not all the effects of the employment protection regulation.

Can wage bargaining cancel out the effects of employment protection laws?

Let me start with a simple example. Suppose the only employment law in New Zealand was a requirement to pay redundancy pay. If wages are flexible, a key analytical assumption that I return to again and again, wage bargaining can completely undo the effects of the redundancy payment mandate by reducing the starting wages paid by the amount of the expected redundancy payment.

Employment protection laws give rise to two costs. The first of these are severance payments, these are transfers of from the employer to the employee. The 2nd type of cost are administrative or procedure costs within the firm and payments to 3rd parties such as for litigation. Advance notice of dismissal and an obligation to find another position within the firm are both administrative costs and transfers to the employee. Administrative costs and severance payments affect employment protection in different ways depending on the presence of wage bargaining. That nuance is completely omitted from the regulatory impact statement.

As illustrated with the example of redundancy pay, if there is no involvement of 3rd parties such as arbitrating the size or eligibility of the payment, it is formula driven by tenure as an example, starting wages are lowered and just as many job vacancies are created. Even if there are some administrative costs involving payments to 3rd parties such as arbitration over the eligibility for redundancy pay or something like that, the expected cost of those payments can be offset by a lower starting wage. This illustrates the effects of employment protection in a barebones manner. The next paragraphs will flash out this analysis.

What do employment protection laws do when no wage bargaining is permitted?

When no wage bargaining is permitted because of the presence of the minimum wage or a wage floor in a collective agreement, the impact of severance pay and procedure costs are the same. They make it less profitable to create vacancies, and less profitable to let people go because of the cost of replacing them. As there are fewer vacancies, there is less employment and spells of unemployment are longer because vacancies are posted less frequently.

When wage bargaining is not permitted either at hiring or when there are productivity shocks cast doubt on the profitability of the job, they have different effects. We are currently considering what happens when there is no wage bargaining

Firing costs certainly do reduce the rate of job destruction. For example, when there is a downturn in demand or some other productivity shock and the entrepreneur believes it is a short-term affair, he can avoid paying the severance pay and administrative costs of the firing by keeping the worker on. Firing costs result in labour hoarding. Employment law protections such as severance pay and any procedure costs encourage labour hoarding. In mild downturns it is cheaper to keep people on than let them go and pay the severance pay and incur various procedural costs.

Firing costs also reduce labour productivity because they induce firms to keep workers at lower productivity levels are slow the rate at which workers are reallocated to new more profitable, higher productivity jobs. This reduces wages in the long-term.

Firing costs have an ambiguous impact on the unemployment rate because they combine two effects that work against each other. By favouring labour hoarding, they reduced job destruction in mild recessions and mild downturns, but they reduced job creation because the higher firing costs downgrades the profit outlook for every new hire. There are fewer jobs, but these jobs last longer. Unemployment spells are also longer because there are fewer vacancies posted.

To complicate the story even more, because unemployment duration is longer and fewer vacancies are posted, labour market tightness is reduced and in consequence the bargaining power of workers is reduced. When labour markets are tight, there are many vacancies and few jobseekers, workers can seek pay rises. But when there are few jobs and long spells of unemployment, the unemployed offer to work for less and incumbent workers fear unemployment.

In summary, when employment protection laws cannot be offset by lower starting wages or other wage negotiations, there is less employment, longer spells of unemployment, lower wages in the long term because of lower productivity, and workers have less bargaining power because of the fear of longer spells of unemployment.

What do employment protection laws do when wage bargaining is possible?

The story complicates no end when wage bargaining is possible. This is because the severance pay and administrative costs or process costs of employment protection laws have different effects. They also cut in at different times.

At hiring stage, wage bargaining could offset both the costs of having to pay severance pay and any administrative costs. But once a vacancy has been filled and the worker hired, when there is a productivity shock, administrative costs, these are payments to 3rd parties, can be avoided if the worker is kept on. Because of this, the incumbent worker might be able to ask for higher wages than otherwise as a way of splitting this saving. The fact that it will cost the employer administrative costs if there is a layoff strengthens the bargaining hand of the employee’s job is at risk.

When the worker is hired, the failure of bargaining over the starting wage incurs neither the severance nor administrative costs of employment law. The twist in the tail is that when wages are renegotiated after hiring such as in the presence of some productivity shock or demand downturn, these costs and transfers are borne by the employer if the wage renegotiation fails. How these costs and the avoidance of these costs takes place depends upon the respective bargaining power of employers and employees and in turn the tightness of the labour market in which those workers will be laid off.

This is a complicated tale. Severance pay can be undone in starting wages, but the costs of firing lends some bargaining power to employees after they hired when wages must re-renegotiated in the face of the demand of productivity shock. But, if employment protection is a particularly strong and therefore the spell of unemployment is long if you do lose your job, labour market tightness offsets any incumbency advantage in the renegotiation of wages in the face of changing economic circumstances for the employer.

What is clear is labour hoarding persists irrespective of wage bargaining options. There are fewer job layoffs so the unemployed must wait longer for vacancies to open. Employment protection unambiguously prolongs spells of unemployment.

What do trial periods do?

The impact of the introduction of trial periods on employment will be ambiguous because the lack of a trial period can be undone by wage bargaining.

- If you hire a worker with full legal protections against dismissal, you pay them less because the employer is taking on more of the risk if the job match goes wrong. If they work out, you promote them and pay them more.

- If you hire a worker on a trial period, they may seek a higher wage to compensate for taking on more of the risks if the job match goes wrong and there is no requirement to work it out rather than just sack them.

The twist in the tail is when there is a binding minimum wage. If there is a binding minimum wage, either the legal minimum or in a collective bargaining agreement, the employer cannot reduce the wage offer to offset the hiring risk so fewer are hired. The introduction of trial periods will affect both wages and employment and employment more in industries that has low pay or often pay the minimum wage.

Trial periods are common in OECD countries. There is plenty of evidence that increased job security leads to less employee effort and more absenteeism. Some examples are:

-

Sick leave spiking straight after probation periods ended;

-

Teacher absenteeism increasing after getting tenure after 5-years; and

-

Academic productivity declining after winning tenure.

Jacob (2013) found that the ability to dismiss teachers on probation – those with less than five years’ experience – reduced teacher absences by 10% and reduced frequent absences by 25%.

Studies also show that where workers are recruited on a trial, employers must pay higher wages. For example, teachers that are employed with less job security, or with longer trial periods are paid more than teachers that quickly secure tenure.

If employers take on more of the risk of a job match going wrong, they will pay recruits less. They can have a promotion round 6 or 12 months where pay is topped up if there is a good match. If minimum wage laws prevent starting salaries going low enough, there will be fewer job vacancies. But higher up the wage scales, the main effect of employment protection laws is to lower wages because the employer expects a wage discount to compensate for taking on more risk of an unsuccessful job match.

Consider, as an example, if there is a requirement to pay redundancy pay. Employers can easily undo this legal requirement by reducing wages. Another similarity is where employers pay completion bonuses on an offshore posting. They back-load compensation to make up for uncertainties about the willingness of the worker to last the posting. Because wages are lower for the duration of the posting, employees expect a big bonus. Also, there is self-selection, recruits are more likely to be those intending to stay for the whole posting. Both the employer and the employee split the greatest surplus from higher quality and longer lasting job matches arising from offering a completion bonus.

What the regulatory impact statement should have said

The regulatory impact statement should have said that many of the effects of employment law on job creation and job destruction can be undone by wage bargaining. But in the case of low paid and minimum wage workers, they have little or any ability to start on lower wages so fewer low paid vacancies will be created, few of them will be destroyed, but what is sure that the low-waged will face longer periods of unemployment.

The adverse effects of employment law on wages growth, productivity growth, and innovation come from their slowing down the rate in which workers are reallocated from old jobs to new jobs because fewer jobs are created and fewer jobs are destroyed.

What do unions still do in the private sector?

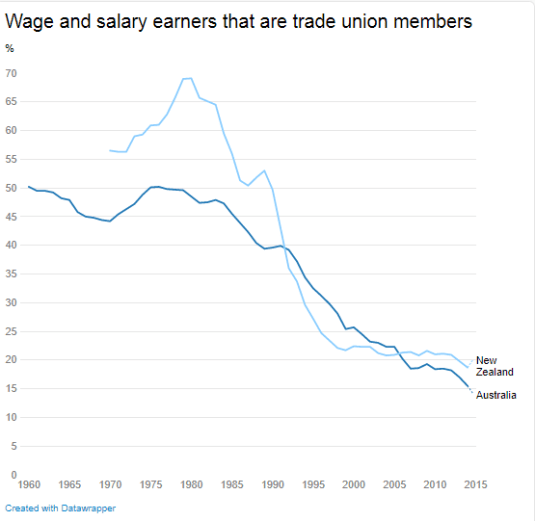

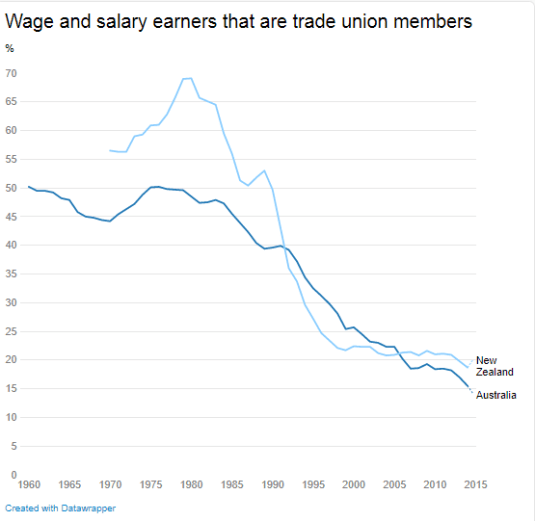

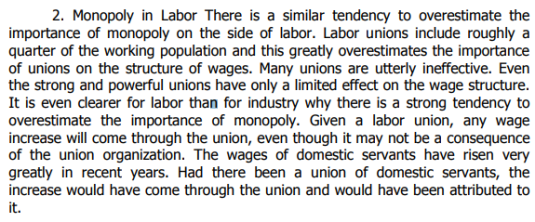

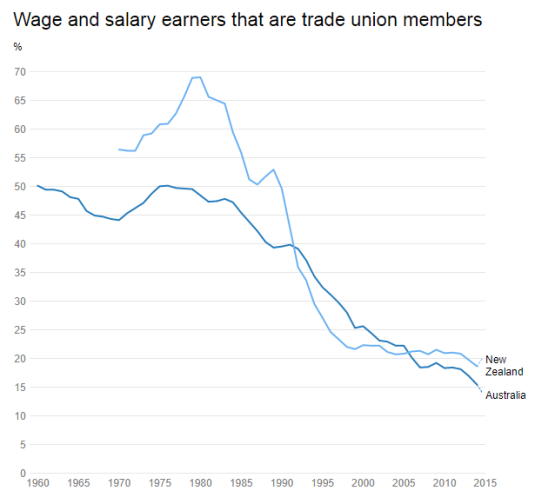

The analysis by the Ministry of the potential effects of unions is out of date. There are now doubts as to whether there is any union wage premium at all. The union wage premium is certainly withering away. Union membership was in freefall until they were saved by the passage of the Employment Contracts Act if simple correlations are to be believed.

Source: OECD Stat Extract.

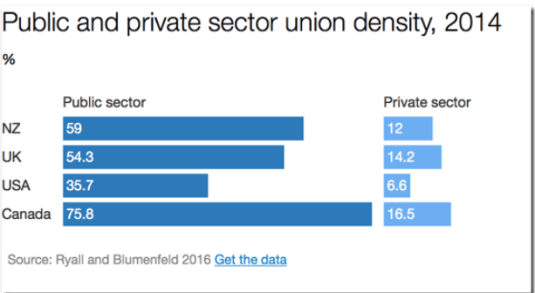

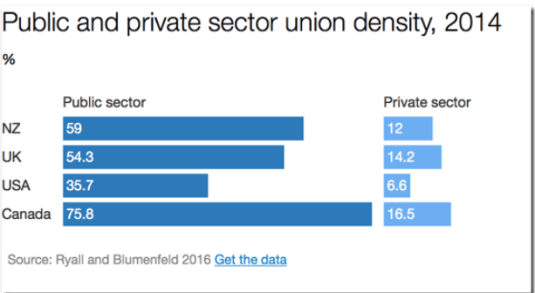

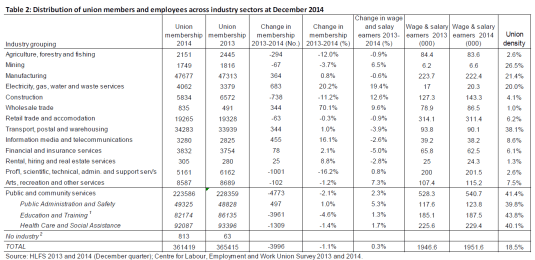

What is clear is unions are dead on their feet in the private sector. Struggling to keep membership in double digits as a share of the private sector workforce both at home and abroad.

Any predictions about the effects of this amendment to the Employment Relations Act provided to you by the Ministry must be set against that background. How union so far gone in the private sector that this bill is more gesture than a real change to the economy?

We are not living in the 70s where most of the workforce are union members. The advice tended to you by officials may well have had some validity 40 years ago, but not now. Furthermore, the evidence doubting the very existence of a union wage premium is growing in jurisdictions where good data is available.

John DiNardo and David Lee compared business establishments from 1984 to 1999 where US unions barely won the union certification election (e. g., by one vote) with workplaces where the unions barely lost. If 50% plus 1 workers vote in favour of the union proposing to organise them, management must bargain for a collective agreement in good faith with the certified union, if the union loses, management can ignore that union.

Most winning union certification elections resulted in the signing of a collective agreement not long after. Unions who barely win have as good a chance of securing a collective agreement as those unions that win these elections by wide margins.

Importantly, few firms subsequently bargained with a union that just lost the certification election. Employers can choose to recognise a union. Because the vote is so close, a workplace becoming unionised was close to a random event.

This closeness of the union certification election may disentangle unionisation from just being coincident with well-paid workplaces, more skilled workers and well-paid industries. Unions could be organising at highly profitable firms that are more likely to grow and pay higher wages independent of any collective bargaining. The unions are possibly claiming credit for wage rises that would have happened anyway.

DiNardo and Lee found only small impacts of unionisation on all outcomes they examined:

This evidence of DiNardo and Lee suggests that in recent decades in the USA, requiring an employer to bargain with a certified union has had little impact because unions have been unsuccessful in winning significant wage gains after unionisation. These findings by DiNardo and Lee suggests that there may not be a union wage premium at all since the early 1980s, at least in the USA.

In another paper DiNardo found a substantial union wage premium before the Second World War by studying the share price effects of unionisation. One of the differences back them that there was far more violence associated with strikes.

We find that strikes had large negative effects on industry stock valuation. In addition, longer strikes, violent strikes, strikes won by the union, strikes leading to union recognition, industry-wide strikes, and strikes that led to wage increases affected industry stock prices more negatively than strikes with other characteristics.

New Zealand and U.S. unions are similar in that both are on their own in bargaining with employers for a wage rise. Options for outside arbitration do not exist in New Zealand; there are some forms of compulsory arbitration in the USA The U.S. result sends a message to New Zealand that unions are a bit of a relic in terms of wage bargaining. MBIE seems to have missed that literature? When there is a literature out there saying that unions have passed into history that must be at least mentioned in passing to this Select Committee.

What the regulatory impact statement should have said

The regulatory impact statement should have said that private-sector unions are few and far between and have little bargaining power. As such, these new laws are unlikely to see a major revival of union membership. There is little evidence that unions have much power to extract higher wages in the private sector.

Summary

In summary, job protection laws reduce wages. For the low paid, they may also reduce employment rates if minimum wage rates are binding. Unions are a dinosaur that do not matter much anymore in the private sector.

Recent Comments