Most early discussions argued against econometric forecasting in principle:

- Forecasting was not properly grounded in statistical theory,

- It presupposed that causation implies predictability, and

- The forecasts themselves were invalidated by the reactions of economic agents to them.

A long tradition argued that social relationships were too complex, too multifarious and too infected with capricious human choices to generate enduring, stable relationships that could be estimated.

These objections came before Hayek’s point that much of all social knowledge is not capable of summation in statistics or even language.

The limitations of forecasting are well-known. Forecasts are conditional on a number of variables; there are important unresolved analytical differences about the operation of the economy; and large uncertainties about the size and timing of responses to macroeconomic changes. Shocks to the output, prices, employment and other variables are partly permanent and partly transitory.

At the practical level, forecasting requires that there are regularities on which to base models, such regularities are informative about the future and these regularities are encapsulated in the selected forecasting model.

We have very little reliable information about the distribution of shocks or about how the distributions change over time. Forecast errors arise from changes in the parameters in the model, mis-specification of the model, estimation uncertainty, mis-measurement of the initial conditions and error accumulation.

In the 1980s, data mining and publications bias were so strong and statistical inferences were so fragile that Ed Leamer’s 1983 Let’s Take the Con out of Econometrics paper made up-and-coming applied economists despair for their professional field and for their own careers:

The econometric art as it is practiced at the computer terminal involves fitting many, perhaps thousands, of statistical models. One or several that the researcher finds pleasing are selected for reporting purposes.

This search for a model is often well intentioned, but there can be no doubt that such a specification search invalidates the traditional theories of inference….

[A]ll the concepts of traditional theory…utterly lose their meaning by the time an applied researcher pulls from the bramble of computer output the one thorn of a model he likes best, the one he chooses to portray as a rose.

… This is a sad and decidedly unscientific state of affairs we find ourselves in.

Hardly anyone takes data analyses seriously.

Or perhaps more accurately, hardly anyone takes anyone else’s data analyses seriously.

Like elaborately plumed birds who have long since lost the ability to procreate but not the desire, we preen and strut and display our t-values [which measure statistical significance].

Leamer still doubts the progress towards techniques that separate sturdy from fragile inferences. Economists by and large simply do not want to hear that they cannot make major conclusions from the data sets. But not that they really do, but that is for a forthcoming post.

Before the great moderation spread wide, Brunner and Meltzer found that in the 1970s and 1980s, the 95% confidence intervals on next year’s forecasts for Gross Domestic Product and the Consumer Price Index are such that government and private forecasters in the USA and Europe could not distinguish between a recession and a boom, nor say whether inflation will be zero or ten per cent.

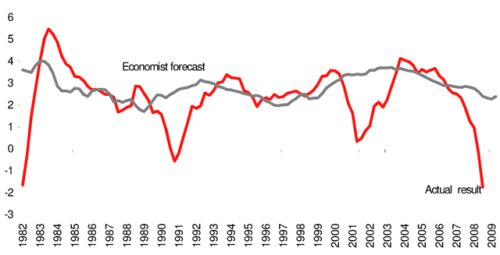

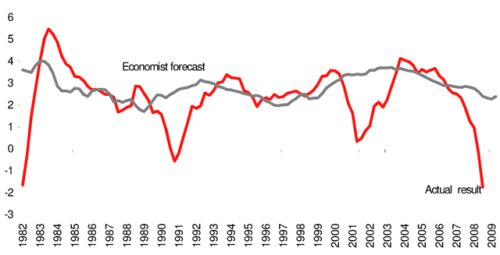

A review this week by Ahir and Lounganishows found that recent forecasting by the private and public sector has not improved:

none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as the previous year was drawing to a close.

Figure 1. Number of recessions predicted by September of the previous year

Source: Ahir and Loungani 2014, “There will be growth in the spring”: How well do economists predict turning points?” http://www.voxeu.org/

A policy-maker who adjusts policy based on forecasts for the following year has little reason to be confident that he has changed policy in the right direction.

While at graduate school, I wrote what was published as Official Economic Forecasting Errors in Australia 1983-96.

Australian Treasury forecasting errors were so large relative to the mean annual rate of change in real GDP and the inflation rate that, on average, forecasters could not distinguish slow growth from a deep recession or stable prices from moderate inflation.

The biography of Paul Keating by Edwards suggested that the Government of the day was well aware of the poor value of forecasts. So much so that forecasts may not have actually played a significant role in monetary policy making in Australia in the late 1980s onwards. John Stone said this to Keating when he assumed office as Treasurer in 1983:

As you know, we (and I in particular) have never had much faith in forecasting.

Not infrequently, our forecasts turn out to be seriously wrong.

… We simply do the best we can, in as professional manner as we can — and, if it is any consolation, no one seems to be able to do any better, at least in the long haul.

We always emphasize the uncertainties that attach to the forecasts — but we cannot ensure that such qualifications are heeded and plainly they often are not

To cast my results in Milton Friedman’s nomenclature for monetary lags, the recognition lag on a forecasting based monetary policy appears to be infinite because forecasters do not know if there will be a recession or 10% inflation afoot when their monetary policy changes take hold in 18 to 24 months.

Recent Comments