@JimRose69872629 @greencatherine response from myself and Jess Berentson-Shaw https://t.co/m4IpYTtGhB 🙂

— Geoff Simmons (@geoffsimmonz) November 29, 2015

Unconscious bias and the gender wage gap

30 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, gender, labour economics, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: gender wage gap, preference formation, unconscious bias

Just testified before a parliamentary committee on zero hours contracts

12 Nov 2015 2 Comments

in labour economics, labour supply, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics, politics - New Zealand, unions Tags: compensating differentials, part-time work, zero hour contracts

My submission to the Transport and Industrial Relations Committee today on the Employment Standards Bill is there should be no regulation of zero hours contracts:

- Workers sign these contracts because they are to their net advantage;

-

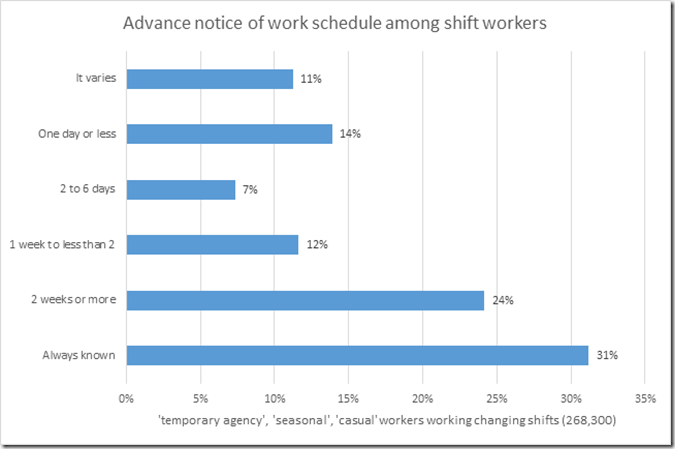

Always knowing your working hours in advance is known only to about 30% of shift workers; and

-

Workers command a wage premium when they sign zero hours contracts.

The obvious question is why do jobseekers sign a zero hours contract if it is not in their interests? Most of all, why would a worker who already has a job quit to work on a zero hours contract unless it is to their advantage?

If zero hours contracts are oppressive, the only workers hired on them would be the unemployed. Anyone who has a job would refuse such offers. Those unemployed that do sign a zero hours contract would quit as soon as a better offer comes along. 50% of job offers to British welfare beneficiaries to work on a zero hours contract are turned down.

This frequent refusal of zero hours contracts not only suggests there are options for jobseekers including the unemployed but there are costs to employers. The most likely employer response to reduce these costs of rejection is a offer to pay more to sign a zero hours contract. Everyone in this room knows contractors who work in much more than those in regular employment.

Unless labour markets are highly uncompetitive with employers having massive power over employees, employers should have to pay a wage premium if zero-hour contracts are a hassle for workers. It is standard for unusual, irregular or casual work to come with a wage premium. If you want regular hours, fixed hours, that comes at a price – a lower wage per hour.

Zero hours contracts is creative destruction in the labour market. Plenty of new ways of working have emerged in recent years: the proliferation of part-time work, temporary workers, leased workers, working from home, teleworking and contracting. Employment laws rest on the now decaying assumption that workers have long, stable relationships with single employers.

At least a quarter of a million New Zealanders already work shifts often with little notice of changes. Work schedules are always known in advance only to 31% of temporary, seasonal and casual employees. Another quarter of these have about two weeks or more notice of shifts. Hundreds of thousands of New Zealand workers freely sign on for variable hours.

Source: Survey of Working Life December Quarter 2012, Statistics New Zealand, Table 13.

Something new and innovative such a zero hours contract should not be regulated because it is not well understood. Zero hours contracts don’t come cheap for employers because of the risk of job offer rejection. There must be offsetting advantages that allow this practice to survive in competition with other ways of hiring a cost competitive labour force.

The fixed costs of recruitment and training are such that one 40-hour worker is cheaper than hiring and training two 20-hour workers. Zero hour contracts would be most likely in jobs with low recruitment costs, few specialised training needs and highly variable customer flows.

This business variability can be borne by the employer with the worker on regular hours but paid less. The alternative is the employee shares this risk with a wage premium for their troubles.

Workers with low fixed costs of working at different times profit from a move onto zero-hours contracts. Those with higher fixed costs of changing their working hours will stay on lower hourly rates but more certain working times

To summarise my points today:

- workers sign zero hours contracts because they are to their advantage to do so;

-

Advance notice of working hours is not as common as people think for shift workers; and

-

Irregular and unusual working arrangements usually command a wage premium.

Employers must pay a wage premium to induce in workers to sign zero hours contracts. This Bill undermines the right of workers to seek those higher wages. Thanks for your time and attention.

More than half of start-ups fail within the first five years

10 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, managerial economics, organisational economics Tags: creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness

Why does Housing New Zealand pay dividends? @chrishipkins @metiria

23 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of bureaucracy, financial economics, industrial organisation, managerial economics, organisational economics, politics - New Zealand

The current controversy over payment of dividends by Housing New Zealand is misplaced because of the subtle connections between payment of dividends and greater value for money.

By paying dividends, the investment priorities of Housing New Zealand are subject to additional ministerial scrutiny. Its capital program is scrutinised in greater detail by the Cabinet because ministers must fund it against competing bids across the entire budget and parliamentary scrutiny process.

Each budget bid is championed by a minister, each of whom must make their case every year against all-comers. This annual competition for a central pool of capital filters out lower value investment bids.

If dividends were not paid but were instead retained as free cash flows in the agency, there would be less ministerial scrutiny of Housing New Zealand because it would have a smaller role in annual budget rounds. Ministers and the Parliament sit up and pay attention when money is to be spent, as they should, and the larger is the sum in the budget, the more attention is paid to value for the money sought. Funding projects with retained dividends may reduce ministerial and parliamentary scrutiny.

Payment of dividends does not reduce the ability of Housing New Zealand to engage in new capital spending. If the dividends were not paid, the amount of new capital spending from budget appropriations would be reduced dollar for dollar.

@NZGreens @GreenpeaceNZ why does @PAKnSAVE charge for plastic bags?

08 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, managerial economics, organisational economics

The 40 PAKnSAVE supermarkets on the North Island charge for plastic bags which you pack for yourself. The 100 New World supermarkets owned by Foodstuffs on the North Island do not charge for plastic bags and the bags are packed for you. The reason is supply and demand that takes account of the full price of groceries including the time cost of shopping and the incomes of their respective customers.

My New World supermarket is just down the road for me – I can see it from my window as I type. The nearest PAKnSAVE is a short drive to a slightly rougher part of town. The PAKnSAVE supermarkets are warehouse style supermarkets rather than a shopping experience made as pleasant as possible and convenient to where you live. PAKnSAVE supermarkets are much larger supermarkets required to be a hub for a number of suburbs rather than one or two.

The type of people who shop at PAKnSAVE are people that the New Zealand Greens pretend to be concerned about. PAKnSAVE customers are lower income people sensitive to prices, willing to go to the trouble of recycling bags.

5p for a plastic bag?

I'm all for a nice little earner, but this is a bleedin' liberty!

#Minder http://t.co/BvfLnjsVy8—

Arthur Daley (@DaleyArfur) October 08, 2015

As you expect under capitalism and freedom, a supermarket chain emerged through market competition to service that more price sensitive niche. The New World supermarket caters more for people in a hurry rather than people on a budget. People on a budget go to PAKnSAVE.

Monday's Daily Mail front page:

Plastic bags chaos looms

#tomorrowspaperstoday #bbcpapers http://t.co/iHHLunYyow—

Nick Sutton (@suttonnick) October 04, 2015

The customers of New World supermarkets are nice members of the middle class who are much more likely to vote Green. They are busy people who do not have the time to keep their bags for next time, much less pack them for themselves. That is before we discuss how unhygienic the recycling of plastic bags is.

Typical of your middle-class Green disposed voter, they are cheapies in a small way as well. When my local supermarket started charging for plastic bags, they quickly dropped the idea because of hostile customer reactions.

The charges are nominal but the people on budgets particularly low income people struggling to with the budget, every cent counts. Naturally the New Zealand Greens are quite dismissive of the cost to shoppers of paying for bags because hardly any of their voters are on a budget.

Typical of the nanny state attitude of the New Zealand Greens, they are happy to compel people to pay for plastic bags and not compensate them for the loss even when they are on low incomes. Do the New Zealand Greens believe plastic bags should be free for low income families?

This same New Zealand Greens pretend to care about poor people who cannot afford to feed their children breakfast, but are happy to make the poor pay for plastic bags.

Let the market sorted it out. There are already supermarkets are charge for plastic bags. Most do not because their customer is uninterested in wasting time paying or bringing their own bags.

I well remember wanting to get time back on my deathbed as we waited behind some arrogant young Green who was packing his own bag after paying for his goods so he kept us waiting for a minute or two.

That is another reason why middle-class supermarkets pack your bags for you. They get you out of the supermarket and away from the lines at the checkouts faster if they pack the bags for you rather than let you do it in a more leisurely pace or perhaps after you have paid.

Again, this is a case about entrepreneurial alertness in the organisation of supermarkets. When your customers are time sensitive, the supermarket does things for them because the supermarket staff can do it faster than they do as they chat to each other and deal with their children.

Roland Fryer On Why Good Schools Matter @greencatherine @dbseymour @ThomasHaig @PPTAWeb

17 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of education, human capital, managerial economics, organisational economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, Public Choice Tags: economics of early childhood education, economics of personality traits, economics of schools, racial discrimination, Roland Fryer

Roland Fryer believes “high-quality education is the new civil rights battleground”. He is an extraordinary man who was carrying a gun and selling drugs at 14 and an assistant professor of economics at Harvard at the age of 27. He is fearless as a researcher.

Source: Roland Fryer On Why Good Schools Matter – Forbes

Roland Fryer is the first Afro-American to win the John Bates Clark Medal econ.st/1FrmzDL http://t.co/QoAZWyRVEX—

Charles Read (@EconCharlesRead) April 27, 2015

Greg Mankiw on the zero influence of modern macroeconomics on monetary policy making

17 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, history of economic thought, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, managerial economics, monetarism, monetary economics, organisational economics Tags: Alan Blinder, Alan Greenspan, credible commitments, Greg Mankiw, modern macroeconomics, monetary policy, neo-Keynesian macroeconomics, new classical macroeconomics, The Fed, timing inconsistency

Two of my brothers studied economics in the early 1970s and then went on to different paths in law and computing respectively. If Greg Mankiw is right, my two older brothers could happily conduct a conversation with a modern central banker. Their 1970s macroeconomics, albeit batting for memory, would be enough for them to hold their own.

Source: AEAweb: JEP (20,4) p. 29 – The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer – Greg Mankiw (2006).

I would spend my time arguing with a central banker that Milton Friedman may be right and central banks should be replaced with a computer. The success of inflation targeting is forcing me to think more deeply about that position. In particular the rise of pension fund socialism means that most voters are very adverse to inflation because of their retirement savings and that is before you consider housing costs are much largest proportions of household budgets these days.

There is a peak stupid

17 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in managerial economics, organisational economics Tags: cognitive psychology, conjecture and refutation, Dunning-Kruger effect

Avoid Mount Stupid http://t.co/PrtPoRX3xJ—

Steve Case (@SteveCase) September 15, 2015

@NZGreens are so polite on Twitter @MaramaDavidson @RusselNorman @greencatherine

12 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, economics of media and culture, liberalism, managerial economics, organisational economics Tags: Cass Sunstein, Daily Me, information cocoons, infotopia, John Stuart Mill, Karl Popper, New Zealand Greens, Twitter, Twitter left

One of the first things I noticed when feuding on Twitter with Green MPs was how polite they were. Twitter is not normally known for that characteristic and that is before considering the limitations of 144 characters. People who are good friends and work together will go to war over email without any space limitations for the making an email polite and friendly. Imagine how easy it is to misconstrue the meaning and motivations of tweets that can only be 144 characters.

The New Zealand Green MPs in their replies on Twitter make good points and ask penetrating questions that explain their position well and makes you think more deeply about your own. Knowledge grows through critical discussion, not by consensus and agreement.

Cass Sunstein made some astute observations in Republic.com 2.0 about how the blogosphere forms into information cocoons and echo chambers. People can avoid the news and opinions they don’t want to hear.

Sunstein has argued that there are limitless news and information options and, more significantly, there are limitless options for avoiding what you do not want to hear:

- Those in search of affirmation will find it in abundance on the Internet in those newspapers, blogs, podcasts and other media that reinforce their views.

- People can filter out opposing or alternative viewpoints to create a “Daily Me.”

- The sense of personal empowerment that consumers gain from filtering out news to create their Daily Me creates an echo chamber effect and accelerates political polarisation.

A common risk of debate is group polarisation. Members of the deliberating group move toward a more extreme position relative to their initial tendencies! How many blogs are populated by those that denounce those who disagree? This is the role of the mind guard in group-think.

Sunstein in Infotopia wrote about how people use the Internet to spend too much time talking to those that agree with them and not enough time looking to be challenged:

In an age of information overload, it is easy to fall back on our own prejudices and insulate ourselves with comforting opinions that reaffirm our core beliefs. Crowds quickly become mobs.

The justification for the Iraq war, the collapse of Enron, the explosion of the space shuttle Columbia–all of these resulted from decisions made by leaders and groups trapped in “information cocoons,” shielded from information at odds with their preconceptions. How can leaders and ordinary people challenge insular decision making and gain access to the sum of human knowledge?

Conspiracy theories had enough momentum of their own before the information cocoons and echo chambers of the blogosphere gained ground.

J.S. Mill pointed out that critics who are totally wrong still add value because they keep you on your toes and sharpened both your argument and the communication of your message. If the righteous majority silences or ignores its opponents, it will never have to defend its belief and over time will forget the arguments for it.

As well as losing its grasp of the arguments for its belief, J.S. Mill adds that the majority will in due course even lose a sense of the real meaning and substance of its belief. What earlier may have been a vital belief will be reduced in time to a series of phrases retained by rote. The belief will be held as a dead dogma rather than as a living truth.

Beliefs held like this are extremely vulnerable to serious opposition when it is eventually encountered. They are more likely to collapse because their supporters do not know how to defend them or even what they really mean.

J.S. Mill’s scenarios involves both parties of opinion, majority and minority, having a portion of the truth but not the whole of it. He regards this as the most common of the three scenarios, and his argument here is very simple. To enlarge its grasp of the truth, the majority must encourage the minority to express its partially truthful view. Three scenarios – the majority is wrong, partly wrong, or totally right – exhaust for Mill the possible permutations on the distribution of truth, and he holds that in each case the search for truth is best served by allowing free discussion.

Mill thinks history repeatedly demonstrates this process at work and offered Christianity as an illustrative example. By suppressing opposition to it over the centuries Christians ironically weakened rather than strengthened Christian belief. Mill thinks this explains the decline of Christianity in the modern world. They forgot why they were Christians.

Israel outdoes Canada in venture capitalism

10 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, financial economics, industrial organisation, managerial economics, organisational economics, survivor principle Tags: creative destruction, Israel, venture capital

The workplace payoff of Myers Briggs personality types

03 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in human capital, labour economics, managerial economics, occupational choice, organisational economics, personnel economics Tags: compensating differentials, economics of personality traits, occupational choice

https://twitter.com/businessinsider/status/626968055046926336/photo/1

Human Resources will assign you a personality…. #HRhumour HT @ssmoir_1973 http://t.co/Vz6vs5ODLw—

Gem Reucroft (@HR_Gem) July 30, 2015

Recent Comments