Churchill on capitalism

14 Sep 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, constitutional political economy, market efficiency, Public Choice, public economics, technological progress Tags: capitalism, Winston Churchill

The most forgotten diagrams in the political economy of taxation-updated

30 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, public economics, taxation Tags: incidence of taxes, the burden of taxes

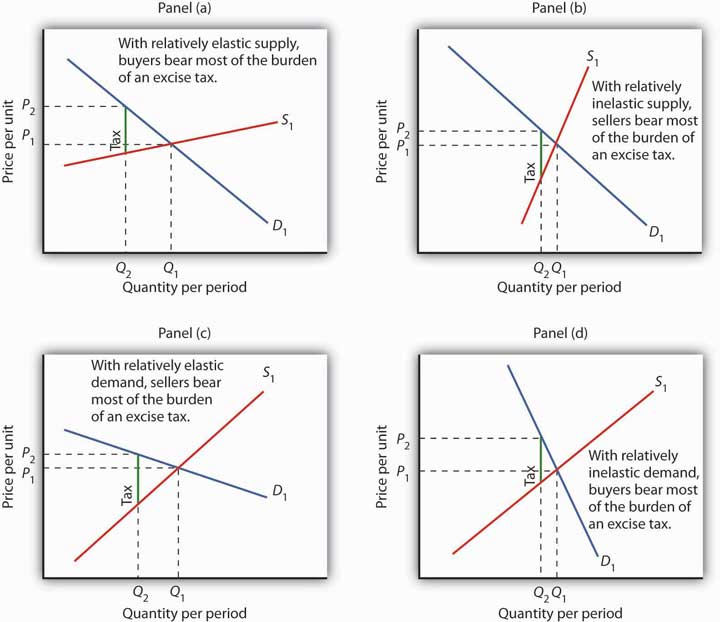

The ability to pass the burden of the tax depends on price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of supply.

The state has no sources of money other than the money people earn themselves

28 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in liberalism, public economics Tags: Margaret Thatcher

Tax Freedom Day

04 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in public economics, taxation Tags: taxes

HT: Daniel Mitchell

Is Thomas Piketty a double secret supply-side economist?

03 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, labour supply, public economics Tags: laffer curve, supply-side economics, Thomas Peketty

When a government taxes a certain level of income or inheritance at a rate of 70 or 80 percent, the primary goal is obviously not to raise additional revenue (because these very high brackets never yield much).

It is rather to put an end to such incomes and large estates, which lawmakers have for one reason or another come to regard as socially unacceptable and economically unproductive…

The Company Tax Laffer curve

03 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in public economics, taxation Tags: company tax rate, laffer curve

The Australian, New Zealand and Irish company taxes raised similar amounts of revenue as a percentage of GDP. The Irish company tax rate was 12.5% in 2003.

from The U.S. Corporate Income Tax System: Once a World Leader, Now A Millstone Around the Neck of American Business by the Tax Foundation via The Solution is the problem blog

Taxing Amazon.com sales | vox

05 May 2014 Leave a comment

in public economics Tags: amazon, substitution effects, tax incidence

When several US states passed laws to require the collection of sales tax on online purchases, households living in these states reduced their Amazon expenditures by 9.5%. In practice, only Amazon was affected by the tax.

The decline in Amazon purchases is offset by a 2% increase in purchases at local brick-and-mortar retailers and a 19.8% increase in purchases through the online operations of competing retailers. The decline in sales is sharpest (23%) for purchases above $300.

Online consumers are very sensitive to total prices, taxes and options to avoid taxes.

Enough taxation can reduce legal marijuana consumption to current regulated levels, and spare us the war on drugs

09 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, law and economics, public economics Tags: illegal goods, marijuana, prohibition

The economics of illegal goods weighs extremely heavily in favour of legalization and taxation rather than banning and enforcing, as Gary Becker, Kevin Murphy, and Michael Grossman outline in The Economic Theory of Illegal Goods: The Case of Drugs (NBER Working Paper, 1994).

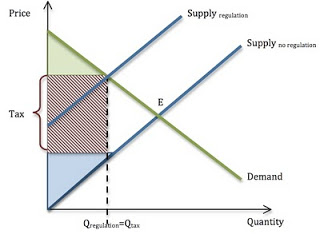

….If the government seeks to regulate the quantity of marijuana consumed, it should choose to do so with a pricing mechanism such as taxation (from which it can earn revenue) rather than a ban (which is costly to enforce). The result is otherwise the same.

Recent Comments