The Great Liberator – Larry Summer’s Obituary for Milton Friedman

30 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in economics, liberalism, Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman explains Director’s Law of of Public Expenditure

29 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in Milton Friedman, Public Choice Tags: Aaron Director

Milton Friedman – links to all of his on-line papers, filmed and taped lectures, TV shows and TV interviews

19 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

see Rose and Milton Friedman at the Hoover Institution for everything on-line in every possible modern and old fashioned media format. For example, if you missed it, watch his ten-part television series Free to Choose and his 46-minute appearance on the Phil Donahue Show

The web page is hard to find through Google unless you know it is already there. Just managed to remembered that it was at the Hoover Institution.

Macroeconomic forecasting has had a turbulent history

16 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman Tags: data mining, Edward Leamer, forecasting, lags on monetary policy

Most early discussions argued against econometric forecasting in principle:

- Forecasting was not properly grounded in statistical theory,

- It presupposed that causation implies predictability, and

- The forecasts themselves were invalidated by the reactions of economic agents to them.

A long tradition argued that social relationships were too complex, too multifarious and too infected with capricious human choices to generate enduring, stable relationships that could be estimated.

These objections came before Hayek’s point that much of all social knowledge is not capable of summation in statistics or even language.

The limitations of forecasting are well-known. Forecasts are conditional on a number of variables; there are important unresolved analytical differences about the operation of the economy; and large uncertainties about the size and timing of responses to macroeconomic changes. Shocks to the output, prices, employment and other variables are partly permanent and partly transitory.

At the practical level, forecasting requires that there are regularities on which to base models, such regularities are informative about the future and these regularities are encapsulated in the selected forecasting model.

We have very little reliable information about the distribution of shocks or about how the distributions change over time. Forecast errors arise from changes in the parameters in the model, mis-specification of the model, estimation uncertainty, mis-measurement of the initial conditions and error accumulation.

In the 1980s, data mining and publications bias were so strong and statistical inferences were so fragile that Ed Leamer’s 1983 Let’s Take the Con out of Econometrics paper made up-and-coming applied economists despair for their professional field and for their own careers:

The econometric art as it is practiced at the computer terminal involves fitting many, perhaps thousands, of statistical models. One or several that the researcher finds pleasing are selected for reporting purposes.

This search for a model is often well intentioned, but there can be no doubt that such a specification search invalidates the traditional theories of inference….

[A]ll the concepts of traditional theory…utterly lose their meaning by the time an applied researcher pulls from the bramble of computer output the one thorn of a model he likes best, the one he chooses to portray as a rose.

… This is a sad and decidedly unscientific state of affairs we find ourselves in.

Hardly anyone takes data analyses seriously.

Or perhaps more accurately, hardly anyone takes anyone else’s data analyses seriously.

Like elaborately plumed birds who have long since lost the ability to procreate but not the desire, we preen and strut and display our t-values [which measure statistical significance].

Leamer still doubts the progress towards techniques that separate sturdy from fragile inferences. Economists by and large simply do not want to hear that they cannot make major conclusions from the data sets. But not that they really do, but that is for a forthcoming post.

Before the great moderation spread wide, Brunner and Meltzer found that in the 1970s and 1980s, the 95% confidence intervals on next year’s forecasts for Gross Domestic Product and the Consumer Price Index are such that government and private forecasters in the USA and Europe could not distinguish between a recession and a boom, nor say whether inflation will be zero or ten per cent.

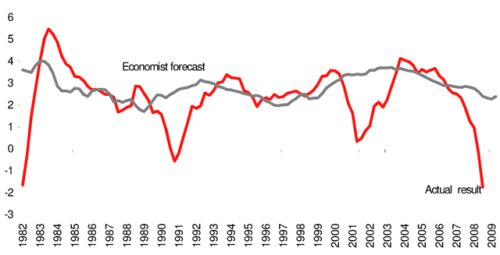

A review this week by Ahir and Lounganishows found that recent forecasting by the private and public sector has not improved:

none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as the previous year was drawing to a close.

Figure 1. Number of recessions predicted by September of the previous year

Source: Ahir and Loungani 2014, “There will be growth in the spring”: How well do economists predict turning points?” http://www.voxeu.org/

A policy-maker who adjusts policy based on forecasts for the following year has little reason to be confident that he has changed policy in the right direction.

While at graduate school, I wrote what was published as Official Economic Forecasting Errors in Australia 1983-96.

Australian Treasury forecasting errors were so large relative to the mean annual rate of change in real GDP and the inflation rate that, on average, forecasters could not distinguish slow growth from a deep recession or stable prices from moderate inflation.

The biography of Paul Keating by Edwards suggested that the Government of the day was well aware of the poor value of forecasts. So much so that forecasts may not have actually played a significant role in monetary policy making in Australia in the late 1980s onwards. John Stone said this to Keating when he assumed office as Treasurer in 1983:

As you know, we (and I in particular) have never had much faith in forecasting.

Not infrequently, our forecasts turn out to be seriously wrong.

… We simply do the best we can, in as professional manner as we can — and, if it is any consolation, no one seems to be able to do any better, at least in the long haul.

We always emphasize the uncertainties that attach to the forecasts — but we cannot ensure that such qualifications are heeded and plainly they often are not

To cast my results in Milton Friedman’s nomenclature for monetary lags, the recognition lag on a forecasting based monetary policy appears to be infinite because forecasters do not know if there will be a recession or 10% inflation afoot when their monetary policy changes take hold in 18 to 24 months.

Milton Friedman on the power of greed

06 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

So that the record of history is absolutely crystal clear. That there is no alternative way, so far discovered, of improving the lot of the ordinary people that can hold a candle to the productive activities that are unleashed by a free enterprise system.

The market is the basis of social peace as well as prosperity

06 Apr 2014 1 Comment

in economics, liberalism, Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman pointed specifically to the anonymity and impersonal nature of the market as a way that people that would otherwise hate each other if they met on any other basis could instead co-operate, work productively together and become friendly with each other.

“The great virtue of a free market system is that it does not care what colour people are; it does not care what their religion is; it only cares whether they can produce something you want to buy. It is the most effective system we have discovered to enable people who hate one another to deal with one another and help one another.”

Benevolence is not enough. The market process ensures that the unpopular and unpleasant also get fed and have jobs. The market is the basis of social peace as well as the only method by which the masses escaped from grinding poverty.

A taxonomy of political disagreement

06 Apr 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, Milton Friedman, politics Tags: Karl Popper

It is just too comforting to think that those you disagree with are ignorant or steeped in moral turpitude, preferably both.

Milton Friedman argued that people agree on most social objectives, but they differ often on the predicted outcomes of different policies and institutions.

This leads us to Robert and Zeckhauser’s taxonomy of disagreement:

Positive disagreements can be over questions of:

1. Scope: what elements of the world one is trying to understand?

2. Model: what mechanisms explain the behaviour of the world?

3. Estimate: what estimates of the model’s parameters are thought to obtain in particular contexts?

Values disagreements can be over questions of:

1. Standing: who counts?

2. Criteria: what counts?

3. Weights: how much different individuals and criteria count?

Any positive analysis tends to include elements of scope, model, and estimation, though often these elements intertwine; they frequently feature in debates in an implicit or undifferentiated manner.

Likewise, normative analysis will also include elements of standing, criteria, and weights, whether or not these distinctions are recognised.

The origin of political disagreement is a broad church indeed in a liberal democracy. Those you disagree with are not evil, they just disagree with you. As Karl Popper observed:

There are many difficulties impeding the rapid spread of reasonableness. One of the main difficulties is that it always takes two to make a discussion reasonable. Each of the parties must be ready to learn from the other.

A nice case against the notion of the ignorance and moral turpitude of your opponents is the obituary by Brad DeLong for Milton Friedman which was as good as any written saying:

His wits were smart, his perceptions acute, his arguments strong, his reasoning powers clear, coherent, and terrifyingly quick. You tangled with him at your peril. And you left not necessarily convinced, but well aware of the weak points in your own argument

AND

Milton Friedman’s thought is, I believe, best seen as the fusion of two strongly American currents: libertarianism and pragmatism. Friedman was a pragmatic libertarian. He believed that–as an empirical matter–giving individuals freedom and letting them coordinate their actions by buying and selling on markets would produce the best results… For right-of-center American libertarian economists, Milton Friedman was a powerful leader. For left-of-center American liberal economists, Milton Friedman was an enlightened adversary. We are all the stronger for his work. We will miss him.

What is neoliberalism? Please tell me – show me one.

27 Mar 2014 4 Comments

in F.A. Hayek, macroeconomics, Milton Friedman, politics - Australia, politics - USA Tags: economic reform, Milton Friedman, neoliberalism, political change

I want to meet someone who believes neoliberalism was the leading light of the economic reforms since 1980. They can then tell me what neoliberalism is. Please, tell me.

The prefix “neo-” makes “neoliberalism” sound like something that morphed into something bad. Is neoliberalism something more than a sustained sneer – a personal attack as a way of avoiding debate?

Not only is there no single definition of neoliberalism, there is no one who identifies himself or herself as a neoliberal. At least communists and socialists were proud to be called so.

In Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan, Taylor Boas & Jordan Gans-Morse went in search of anyone who identifies one’s self as a neoliberal:

- They did not uncover a single contemporary instance in which an author used the term self-descriptively, and only one – an article by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman (1999) – in which neoliberal was applied to the author’s own policy recommendations.

- Digging into the archives, they did find that while Milton Friedman (1951) embraced the neoliberal label and philosophy in one of his earliest political writings, he soon distanced himself from the term, trumpeting “old-style liberalism” in later manifestoes (Friedman 1955). See “Neo-liberalism and its Prospects”, Milton Friedman Papers, Box 42, Folder 8, Hoover Institution Archives. 1951. Hardly a smoking gun?

What Boas and Gans-Morse found, based on a content analysis of 148 journal articles published from 1990 to 2004, was that the term is often undefined. It is employed unevenly across ideological divides; it is used to characterise an excessively broad variety of phenomena.

That is academic speak for neoliberalism is an empty slogan.

Neoliberalism was supposed to rule the roost under Reagan, Thatcher, Hawke and Lange-Douglas. The local branches of neoliberalism were Thatchernomics, Rogernomics, and Reaganomics.

Milton Friedman is said to have mesmerised several countries with a flying visit. The Friedman Monday Conference on ABC in 1975 and by Hayek in 1976 are still ruling the Australian policy roost, if some serious public commentators are to be believed.

In the 1980s and up to the mid-1990s, despite all the neo-liberal deregulation and Milton Friedman taking over monetary policy, mentioning Friedman’s name at job interviews would have been extremely career limiting, and that was at the Australian Treasury.

Back then, the much less radical Friedman was just graduating from being a wild man in the wings to just a suspicious character.

If you name dropped Hayek in the early 1990s, any sign of name recognition would have indicated that you were being interviewed by educated people.

When the Left gets on its high horse and goes on about Hayek and Friedman running neoliberalism, with Hayek as Friedman’s mentor, it is refreshing to remind all how little they had in common on macroeconomics. The University of Chicago Department of Economics did not offer Hayek a job in the late 1940s despite his outstanding record at LSE as Keynes’ principal critic in the 1930s.

While working at the next desk to a monetary policy section in the late 1980s, when mortgage rates were 18%, I heard not a word of Friedman’s Svengali influence:

- The mantra for several years was that the market determined interest rates, not the Reserve Bank. Joan Robinson would have been proud that her 1975 Monday conference was still holding the reins.

- Monetary policy was targeting the current account. Read Edwards’ biography of Paul Keating’s time as Treasurer and Prime Minister and his extracts from very Keynesian treasury briefings to Keating signed by David Morgan that reminded me of Keynesian Macro 101.

As a commentator on an Australian Treasury seminar paper in 1986, Peter Boxhall – freshly educated from the 1970s Chicago School – suggested using monetary policy to reduce the inflation rate quickly to zero. David Morgan and Chris Higgins almost fell off their chairs. These Treasury Deputy CEOs had never heard of such radical ideas.

In their breathless protestations, neither Morgan nor Higgins were sufficiently in tune with their Keynesian education to remember the role of sticky wages or even the need for monetary growth reductions to be gradual and, more importantly, credible, as per Milton Friedman.

By the way, Friedman’s presidential address to the AEA in 1967 is now recognised as perhaps the single most influential journal article of the 20th century. That article is the essence of good communication and empirical testing of competing hypotheses as was his 1976 Noble Prize lecture. No wonder both were hidden from impressionable undergraduates such as me a few years after.

Recent Comments