How to eliminate the gender wage gap in one easy step! Marry down? @women_nz @JulieAnneGenter

12 Oct 2019 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, discrimination, economic history, economics of love and marriage, entrepreneurship, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, marriage and divorce

The dark underbelly of the signalling value of engagement rings

19 Apr 2017 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, television Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, comparable worth, dating markets, gender, marriage and divorce, Seinfeld, signalling

The gender commuting gap between mothers and fathers

28 Aug 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, transport economics Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, commuting times, compensating differentials, female labour force participation, gender gap, gender wage gap

The first three bars in each cluster of bars are for men. in almost all countries mothers with dependent children spend less time commuting than childless women. This might suggest that working mothers have found workplaces closer to home than women without children. The gender gap in commuting where it is present in the country is larger than the gap between mothers and other women in their commuting time.

Source: OECD Family Database – OECD, Table LMF2.6.A.

Time spent in paid and unpaid work across the OECD by gender

30 Jul 2016 1 Comment

in economics of love and marriage, gender, labour economics, labour supply Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, female labour force participation, household production, marital division of labour

The importance of talking to your children @GreenCatherine @jacindaardern @Maori_party

06 May 2016 Leave a comment

Median Income for Married Couples with Both Spouses Working

23 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of love and marriage, labour economics Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, middle class stagnation, pessimism bias, wage stagnation

Poverty rates in two-earner families in the USA

19 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, child poverty, family poverty

HT: Matt Bruenig

No asymmetric marriage premium in commuting: the family commuting gap for mothers and fathers travelling to and from work by school age of child in the UK, Germany, France and Italy

04 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, transport economics, urban economics Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, commuting times, gender wage gap, reversing gender gap

Few labour market statistics have any meaning unless broken down by gender. The compensating differentials that explain much of the family pay gap extend strongly to commuting times.

Source: OECD Family Database – OECD, Table LMF2.6.A.

Mothers commute a good 15 to 20 minutes less than fathers in the UK, Italy, Germany and France. Single women commute 5 to 10 minutes further than mothers. Single men and fathers commute much the same distance.

Greater maternity leave will increase the gender wage gap

31 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, high-powered jobs, offsetting behaviour, Parental leave, paternity leave, unintended consequences

Haggling and the gender pay gap

29 Jan 2016 1 Comment

in discrimination, economics of love and marriage, gender, job search and matching, labour economics, occupational choice Tags: asymmetric marriage premium, gender wage gap, marital division of labour, marriage and divorce

Geoff Simmons attributes part of the gender wage gap to the reluctance especially among women in high-paying jobs to haggle over pay. These women at the top end of the labour market are more likely to accept the first offer.

This relative reluctance of women to haggle over their pay is important to explaining why the gender wage gap is much larger at the top end of the labour market than at the bottom according to Geoff Simmons. Women have to haggle more if the gender pay gap is to close further.

Haggling over the wage has costs as well as benefits as Richard Epstein explained 20 years ago within a search and matching framework when commenting on a paper written by Carol Rose in 1992:

If one party is known to gobble up virtually all the cooperative surplus, then that party will find it difficult to attract deals. People anticipate getting some portion of the gain and will have a tendency to migrate to other individuals and transactions when they do not have to be ever watchful of their fair share of the gain.

If women have the characteristics that Rose attributes to them, then they would be able to enter more deals and find jobs more easily than men. At this point it becomes an empirical question: whether the greater frequency of deals (or shorter periods of unemployment) offset the tendency to gain a larger share of the profits of any given transaction.

Women will find it easier to get a job because they haggle less and therefore negotiations are less likely to breakdown, which will increase their lifetime income. This reduction in the cost of search because of a greater prospect of a match offset the losses in wages from successful haggling.

Indeed, does not this reluctance to haggle among women make it more likely that employers will hire women and promote the because their reluctance to haggle makes them cheaper. This starts off a competition between employers that will slowly drive up the wages offered to women.

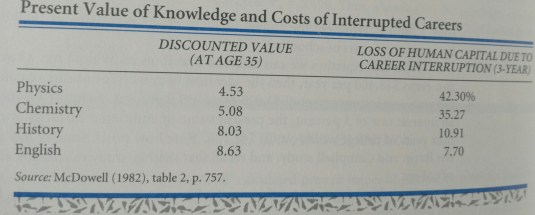

It is also the case that women invest in human capital that is more mobile between the jobs and they are more likely to quit the workforce and return again after motherhood.

The ability to quickly find a job after a career interruption is a competitive advantage rather than a disadvantage.

Men have more specialised human capital and are more likely to stay in one job so they have more to gain from haggling. In comparison, women invest in human capital that is more mobile between jobs because they anticipate downscaling or quitting because of motherhood.

In such a case, it is advantageous to have human capital that appeals to a wide range of employers and become can be quickly matched so that full-time or part-time employment and the associated income stream can start quick as quickly as possible. Workers who changed jobs more often and have shorter job tenures have less to gain and more to lose from haggling and not getting the job at all.

If women do not like to haggle, does this not imply they are less likely to be attracted the jobs with performance pay? Alan Manning investigated this specific question a few years ago.

The propensity of women to seek or avoid jobs with performance pay in a more competitive workplace is an important question because up to 40% of jobs have some form of performance pay which would put women off if they do not like to haggle as Geoff Simmons implies.

Manning used jobs with performance pay in the the 1998 and 2004 British Workplace Employees Relations Survey as a proxy for the level of competition in the workplace.

If Geoff Simmons is right, women should shy away from jobs with performance pay. Women should be less likely to hold these jobs with performance pay, other things being equal. That is precisely the hypothesis that Alan Manning explored. He is a world-class labour economist. What did he find?

We find very modest evidence for differential sorting into performance pay schemes by gender, and small effects of performance pay on hourly wages. Furthermore, and unlike the laboratory studies, we find no significant effect of the gender mix in the job on the responsiveness to performance pay.

We do find some evidence for an effect of performance pay on a measure of work effort in line with the experimental evidence but the bottom line is that a very small part of the gender pay gap can be attributed to these factors.

The gender pay is already tiny in New Zealand and only a tiny part of that can be explained as any reluctance of women to compete in the workforce such as through signing on for performance pay.

Manning found that the gender mix of jobs in occupation is not affected by the presence of performance pay but it should be if women are reluctant to angle and to be competitive as suggested by Geoff Simmons.

The reluctance of women to sign on for performance pay maybe be an aspect of the asymmetric marriage premium and the marital division of effort. Mothers, unlike fathers, cannot afford to go home at the end of the workday completely exhausted if there are children to care for.

Women have a long history of carefully selecting education and other human capital and occupations to anticipate the responsibilities of motherhood and minimising human capital depreciation during the associated career interruptions. Anticipating that motherboard is a lot of work is no stretch on that occupational sorting by women.

Women still do most of the household chores? Data on who does what in the house: goo.gl/3doqy4 #statistics https://t.co/fnY0d9OgkT—

DataStories (@LindaRegber) October 24, 2015

That division of effort between the sexes has got nothing to do with the behaviour of employers and everything to do with the marital division of labour. As to what to do about that Richard Posner raised a very good conundrum in a paper from 20 years ago:

The idea the government should try to alter the decisions of married couples on how to allocate time to raising children is a strange mixture of the utopian and the repulsive. The division of labour within marriage is something to be sorted out privately rather than made a subject of public intervention.

Liberal and radical frameless can if they wanted women to stay in the labour force and have no children or fewer children, or, persuade their husbands to assume a greater role in child rearing. Others can search the contrary. The ultimate decision is best left to private choice.

I remember from decades ago a couple at work who were very modern and trying to share the child rearing equally. Their three-year-old daughter was not very cooperative because she found that her mother was much better at braiding her hair than a father. That tantrum by their three-year-old was the beginning of the end of a grand plan.

Recent Comments