David Friedman on the causes of the global financial crisis and the great recession

16 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

Rational Criminals and Profit-Maximizing Police

15 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in David Friedman, economics of crime, entrepreneurship, law and economics Tags: David Friedman, economics of crime, Gary Becker

Legal Systems Very Different from Ours – David Friedman’s forthcoming book

14 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, David Friedman, law and economics Tags: comparative economic analysis, comparative law, David Friedman, law and economics, Legal systems very different to ours

The central idea of David Friedman’s forthcoming book on legal systems of different societies is they face similar problems and solve them, or fail to, in an interesting variety of ways.

Looking at a range of such societies and trying to make sense of their legal systems provides a window into both problems and solutions, useful for the general project of understanding law—in particular but not exclusively from an economic point of view—and for the narrower project of improving it.

Unlike the usual course in comparative law, he did not look at systems close to ours such as modern Civil Law or Japanese law. Instead, Friedman examined systems from the distant past (Athens, Imperial China), from radically different societies (saga period Iceland, Sharia), or contemporary systems independent of government law (gypsy law, Amish).

System Chapters

Icelandic Law

18th c. English Criminal Law

Gypsy Law

Chinese Law

Athenian Law: The Work of a Mad Economist

Jewish Law

Islamic Law [Recently Updated]

Plains Indian Law

Puzzles of Irish Law

Amish Law

Somali Law [Recently Updated]

Commanche, Kiowa and Cheyenne: The Plains Indians

Thread Chapters

Enforcement Mechanisms: Civil, Criminal, And Lots More

The Incentive to Enforce: What and How Much

Embedded and Polylegal Systems

God as Legislator

Making Law

Guarding the Guardians

His Class web page is based on Student Papers from the SCU Seminar

David Friedman on Director’s law and and poverty and inequality under capitalism

13 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, David Friedman, Marxist economics Tags: David Friedman, Director's Law, poverty versus inequality, That Great Enrichment

HT: Cafe Hayek

Market Failure, Considered as an Argument both for and Against Government| David Friedman

24 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, David Friedman, liberalism, libertarianism Tags: David Friedman, externality, government failure, market failure

On net, are the results good or bad?

13 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, David Friedman, law and economics Tags: David Friedman

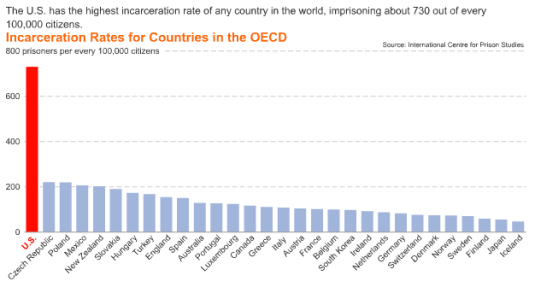

Prison numbers are too high?

11 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in David Friedman, economics of crime, labour economics, law and economics Tags: crime and punishment, David Friedman, prison numbers

How can prison numbers be too high? There are unsolved crimes: murders, robberies, sexual assaults and burglaries to name a few.

There are people out there who should have been arrested, convicted and sent to prison for serious crimes. Many of them are repeat offenders and career criminals.

I have never understood the reasoning behind the notion that prison numbers are too high.

Concerns about prison numbers being too high is exclusively a concern about the criminals who were sent to prison. Their victims are never mentioned nor are victims of unsolved crime who have been denied justice.

There is an economic literature on the efficient level of crime. Those that are concerned about prison numbers being too high explicitly reject the economics of crime literature for the purpose of framing public policy about criminal justice. The reason is obvious from this passage by David Friedman:

The economic analysis of crime starts with one simple assumption: Criminals are rational.

A mugger is a mugger for the same reason I am a professor-because that profession makes him better off, by his own standards, than any other alternative available to him.

Here, as elsewhere in economics, the assumption of rationality does not imply that muggers (or economics professors) calculate the costs and benefits of available alternatives to seventeen decimal places-merely that they tend to choose the one that best achieves their objectives.

If muggers are rational, we do not have to make mugging impossible in order to prevent it, merely unprofitable.

If the benefits of a profession decrease or its costs increase, fewer people will enter it-whether the profession is plumbing or burglary.

If little old ladies start carrying pistols in their purses, so that one mugging in ten puts the mugger in the hospital or the morgue, the number of muggers will decrease drastically-not because they have all been shot but because most will have switched to safer ways of making a living.

If mugging becomes sufficiently unprofitable, nobody will do it.

Putting more offenders in prison should decrease crime by both incapacitating incarcerated offenders and deterring potential offenders.

David Friedman – Market Failure: An Argument Both For and Against Government

04 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, constitutional political economy, David Friedman Tags: comparative institutional analysis, David Friedman, government failiure, market failure

David Friedman “Global Warming, Population, and the Problem with Externality Arguments”

01 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

The economics of the Dallas Buyers Club

15 Mar 2014 Leave a comment

in liberalism, politics - Australia, politics - USA, Public Choice, regulation Tags: AIDS, AZT, Dallas Buyers Club, David Friedman, drug lags, FDA, Matthew McConaughy, Sam Peltzman

Deciding if a new drug is safe is a serious issue. Separate to this is whether the drug is better than existing drugs.

In 1962, an amended law gave the FDA authority to judge if a new drug produced the results for which it had been developed. Formerly, the FDA monitored only drug safety. It previously had only sixty days to decide this. Drug trials can now take up to 10 years.

Who cares if a safe drug works or not? If a new drug does not work or is no better than the existing drugs on the market, the investors in the development of the new drug bear the (unrecoverable) development costs. Capitalism is a profit AND loss system. Losses are a signal that you should try something else.

Sam Peltzman showed in a famous paper in 1973 that these 1962 amendments reduced the introduction of effective new drugs in the USA from an average of forty-three annually in the decade before the 1962 amendments to sixteen annually in the ten years afterwards. No increase in drug safety was identified.

Drugs became available years after they were on the market outside the USA. To quote David Friedman:

“In 1981… the FDA published a press release confessing to mass murder. That was not, of course, the way in which the release was worded; it was simply an announcement that the FDA had approved the use of timolol, a ß-blocker, to prevent recurrences of heart attacks.

At the time timolol was approved, ß-blockers had been widely used outside the U.S. for over ten years.

It was estimated that the use of timolol would save from seven thousand to ten thousand lives a year in the U.S. So the FDA, by forbidding the use of ß-blockers before 1981, was responsible for something close to a hundred thousand unnecessary deaths.”

AZT double-blind trials collapsed in the mid-1980s in the USA because participants sold the drug in the black market.

If memory serves right, Australian drug regulators planned to duplicate these double-blind trials in Australia before approving the drug. Last time I checked, the physiology of Australians was the same as any other human being. What did they plan to find that justified the delay in approving AZT?

The duplicate double-blind AZT trials in Australia were abandoned not because they were mad and evil, but because again the participants sold the drug in the black market. That was to be expected too so the duplicate double-blind AZT trials in Australia in the 1980s were a double evil.

Recent Comments