.

There is not a lot of inflation out there

17 Mar 2016 Leave a comment

in macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: deflation, inflation rate, liquidity trap, monetary policy

Has New Zealand been in deflation since 2012?

21 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

in global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: CPI bias, deflation, inflation, monetary policy

All agree that the consumer price index (CPI) is biased and overstates inflation. In 1996, economists hired by the Senate Finance Committee estimated that the U.S. CPI overstates annual inflation by 1.1% (Boskin et al. 1996). That estimated CPI bias has not gotten smaller with time. It is now up to 1.5%, even 2%.

One of the rationales for the inflation target of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand of 0-2% was the 2% was to account for the consumer price index was biased upwards. Targeting 0% would lead to mild deflation when inflation was properly measured.

The main biases in the consumer price index everywhere come from how to handle changes in the quality of goods and services and how to deal with completely new goods and services.

I thought I might see what happened if I took this one and a half percentage point annual bias in the CPI estimated for the USA and adjusted the New Zealand CPI inflation rates available at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s website over the last 20 years or so with this number.

If these consumer price index bias adjustments are correct, and they are roughly correct, inflation came to a dead stop in New Zealand after the global financial crisis in 2008, spiked again, and then moved into deflation in 2012. If anything, there’s been a mixture of price stability and the deflation since 2012.

People get quite hot and bothered with deflation. The New Zealand economy has been in a deflationary phase since the beginning of 2012 but it is recently grown so quickly that it is referred to in the media as the rock-star economy.

Breathless journalism aside , fears of inflation are just a legacy of the great depression in the 1930s. The only depression where deflation was accompanied by mass unemployment was the Great Depression. Mild deflation with good growth is a common phenomena as Atkinson and Kehoe found:

Are deflation and depression empirically linked? No, concludes a broad historical study of inflation and real output growth rates.

Deflation and depression do seem to have been linked during the 1930s. But in the rest of the data for 17 countries and more than 100 years, there is virtually no evidence of such a link.

Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?

31 Jan 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, Euro crisis, great depression, great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: deflation, fiscal policy, liquidity traps, monetary policy, stabilisation policy

Deflation has a bad reputation. People blame deflation for causing the great depression in the 1930s. What worse reputation can you get as a self-respecting macroeconomic phenomena?

The inconvenient truth for this urban legend is empirical evidence of deflation leading to a depression is rather weak.

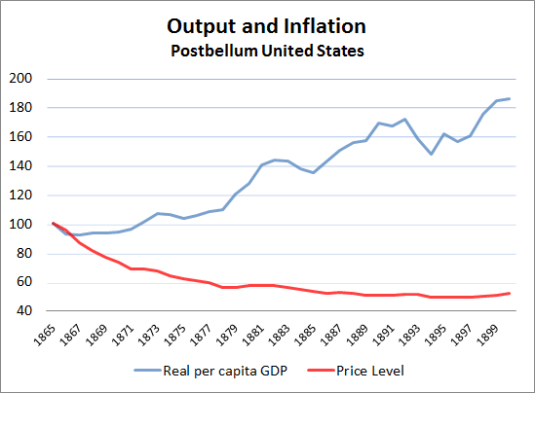

The most obvious is confounding evidence, is up until the great depression, deflation was commonplace. In the late 19th century, deflation coincided with strong growth, growth so strong that it was called the Industrial Revolution.

For deflation to be a depressing force, something must have happened in the lead up to the Great Depression to change the impact of deflation on economic growth.

Atkeson and Kehoe in the AER looked into the relationship between deflation and depressions and came up empty-handed.

Deflation and depression do seem to have been linked during the 1930s. But in the rest of the data for 17 countries and more than 100 years, there is virtually no evidence of such a link.

Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?

Andrew Atkeson, and Patrick J. Kehoe, 2004.

Are deflation and depression empirically linked? No, concludes a broad historical study of inflation and real output growth rates. Deflation and depression do seem to have been linked during the 1930s. But in the rest of the data for 17 countries and more than 100 years, there is virtually no evidence of such a link.

View original post 1,842 more words

Recent Comments