Creative destruction in content control

01 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of media and culture, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, survivor principle Tags: consumer sovereignty, creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, media bias

I might do most of these. Do you?

31 May 2015 2 Comments

in economics of media and culture, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation Tags: cell phones, creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, PCs, smart phones

Does Inequality Reduce Economic Growth: A Sceptical View

30 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, development economics, economic history, entrepreneurship, growth disasters, growth miracles, income redistribution, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking Tags: entrepreneurial alertness, Leftover Left, taxes and the labour supply, The inequality and growth, Thomas Piketty, top 1%, Twitter left

Tim Taylor, the editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, has written a superb blog post on why we should be sceptical about a strong relationship between inequality and economic growth. Taylor was writing in response to the OECD’s recent report "In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All,".

Taylor’s basic point is economists have enough trouble working out what causes economic growth so trawling within that subset of causes to quantify the effects of rising or falling inequality inequality seems to be torturing the data to confess. The empirical literature is simply inconclusive as Taylor says:

A variety of studies have undertaken to prove a connection from inequality to slower growth, but a full reading of the available evidence is that the evidence on this connection is inconclusive.

Most discussions of the link between inequality and growth are notoriously poor of theories connecting two. There are three credible theories in all listed in the OECD’s report:

The report first points out (pp. 60-61 that as a matter of theory, one can think up arguments why greater inequality might be associated with less growth, or might be associated with more growth. For example, inequality could result less growth if:

1) People become upset about rising inequality and react by demanding regulations and redistributions that slow down the ability of an economy to produce growth;

2) A high degree of persistent inequality will limit the ability and incentives of those in the lower part of the income distribution to obtain more education and job experience; or

3) It may be that development and widespread adoption of new technologies requires demand from a broad middle class, and greater inequality could limit the extent of the middle class.

About the best theoretical link between inequality and economic growth is what Taylor calls the "frustrated people killing the goose that lays the golden eggs." Excessive inequality within a society results in predatory government reactions at the behest of left-wing or right-wing populists.

Taylor refers to killing the goose that laid the golden egg as dysfunctional societal and government responses to inequality. He is right but that is not how responses to inequality based on higher taxes and more regulation are sold. Thomas Piketty is quite open about he wants a top tax rate of 83% and a global wealth tax to put an end to high incomes:

When a government taxes a certain level of income or inheritance at a rate of 70 or 80 percent, the primary goal is obviously not to raise additional revenue (because these very high brackets never yield much).

It is rather to put an end to such incomes and large estates, which lawmakers have for one reason or another come to regard as socially unacceptable and economically unproductive…

The left-wing parties don’t say let’s put up taxes and redistribute so that is not something worse and more destructive down the road. Their argument is redistribution will increase growth or at least not harm it. That assumes the Left is addressing this issue of not killing the goose that lays the golden egg at all.

Once you discuss the relationship between inequality and growth in any sensible way you must remember your John Rawls. Incentives encourage people to work, save and invest and channels them into the occupations where they make the most of their talents. Taylor explains:

In the other side, inequality could in theory be associated with faster economic growth if: 1) Higher inequality provides greater incentives for people to get educated, work harder, and take risks, which could lead to innovations that boost growth; 2) Those with high incomes tend to save more, and so an unequal distribution of income will tend to have more high savers, which in turn spurs capital accumulation in the economy.

Taylor also points out that the OECD’s report is seriously incomplete by any standards because it fails to mention that inequality initially increases in any poor country undergoing economic development:

The report doesn’t mention a third hypothesis that seems relevant in a number of developing economies, which is that fast growth may first emerge in certain regions or industries, leading to greater inequality for a time, before the gains from that growth diffuse more widely across the economy.

At a point in its report, the OECD owns up to the inconclusive connection between economic growth and rising inequality as Taylor notes:

The large empirical literature attempting to summarize the direction in which inequality affects growth is summarised in the literature review in Cingano (2014, Annex II).

That survey highlights that there is no consensus on the sign and strength of the relationship; furthermore, few works seek to identify which of the possible theoretical effects is at work. This is partly tradeable to the multiple empirical challenges facing this literature.

The OECD’s report responds to this inclusiveness by setting out an inventory of tools with which you can torture the data to confess to what you want as Taylor notes:

There’s an old saying that "absence of evidence is not evidence of absence," in other words, the fact that the existing evidence doesn’t firmly show a connection from greater inequality to slower growth is not proof that such a connection doesn’t exist.

But anyone who has looked at economic studies on the determinants of economic growth knows that the problem of finding out what influences growth is very difficult, and the solutions aren’t always obvious.

The chosen theory of the OECD about the connection between inequality and economic growth is inequality leads to less investment in human capital at the bottom part of the income distribution.

[Inequality] tends to drag down GDP growth, due to the rising distance of the lower 40% from the rest of society. Lower income people have been prevented from realising their human capital potential, which is bad for the economy as a whole

I found this choice of explanation curious. So did Taylor as the problem already seems to have been solved:

There are a few common patterns in economic growth. All high-income countries have near-universal K-12 public education to build up human capital, along with encouragement of higher education. All high-income countries have economies where most jobs are interrelated with private and public capital investment, thus leading to higher productivity and wages.

All high-income economies are relatively open to foreign trade. In addition, high-growth economies are societies that are willing to allow and even encourage a reasonable amount of disruption to existing patterns of jobs, consumption, and ownership. After all, economic growth means change.

In New Zealand, interest free student loans are available to invest in higher education as well as living allowances for those with parents on a low income. There are countries in Europe with low levels of investment in higher education but that’s because of high income taxes not because of inequality.

The OECD’s report is fundamentally flawed which is disappointing because most research from the OECD is to a good standard.

via CONVERSABLE ECONOMIST: Does Inequality Reduce Economic Growth: A Skeptical View.

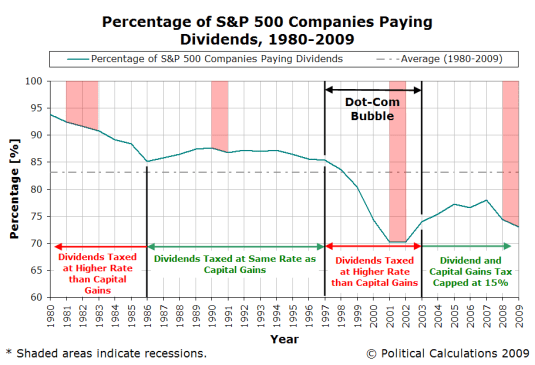

Did changes in capital gains and dividend tax rates caused the dot.com bubble to begin and end?

30 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, public economics Tags: capital gains tax, dot.com bubble, entrepreneurial alertness, tax arbitrage

…the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 left dividend tax rates unchanged – they continued to be taxed at the same rates as regular income in the United States, which provided a powerful incentive for investors to treat the two kinds of stocks very differently, favouring the low-to-no dividend paying stocks over those that paid out more significant dividends.

At least, until May 2003, when the compromises that led to, and ultimately the signing of the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 would set both the tax rates for capital gains and for dividends to once again be equal to one another, as they had been in the years from 1986 through 1997…

the founding and rapid growth of new computer and Internet technology-oriented companies in the early 1990s, which grew rapidly to become large companies and which as growth companies, did not pay significant dividends to shareholders, provided the critical mass needed for the 1997 capital gains tax cut to launch the Dot Com Bubble.

via Political Calculations: What Caused the Dot Com Bubble to Begin and What Caused It to End?.

Facebook started 10 years ago today

29 May 2015 Leave a comment

10 years ago today Facebook was founded by Mark Zuckerberg and his college friends http://t.co/IVFDFvu2VM—

History Pics (@HistoryPixs) February 04, 2014

The rise and rise of working billionaires

23 May 2015 Leave a comment

Big business is getting bigger

22 May 2015 Leave a comment

If it seems like big business is getting bigger, it is: 53eig.ht/1L127cr http://t.co/OX9eSj01yc—

(@FiveThirtyEight) May 18, 2015

Entrepreneurial alertness alert: Las Vegas advertised itself as a place to watch the nearby nuke tests

19 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, entrepreneurship, politics - USA Tags: atomic bomb tests, entrepreneurial alertness, Las Vegas

Back in the 1950s, Las Vegas advertised itself as a place to watch the nearby nuke tests. Bring the whole family! http://t.co/zMrCdskYLk—

Weird History (@weird_hist) December 06, 2014

Maybe this is why Twitter is struggling a bit

17 May 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, entrepreneurship Tags: creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, Facebook, market selection, The meaning of competition, Twitter

According to @Shareaholic, Facebook drives 20x as much traffic to websites as Twitter does statista.com/chart/2480/twi… http://t.co/c2TRVndt4K—

Statista (@StatistaCharts) July 22, 2014

More evidence of the rise and rise of the working rich, who build businesses

17 May 2015 1 Comment

in economic history, entrepreneurship Tags: CEOs, creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%

Er: more taxes on capital and wealth, anyone? (CBO latest). http://t.co/PT95Py3USu—

Richard V. Reeves (@RichardvReeves) November 17, 2014

The robots are coming, the robots are coming to property values

16 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economics of media and culture, entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, survivor principle, technological progress, transport economics, urban economics Tags: agglomeration, compensating differentials, creative destruction, driverless cars, drones, entrepreneurial alertness, land prices, land supply

A few years ago, Casey Mulligan wrote a fascinating little op-ed about the impact of drones on land prices and urban living.

As drones and driverless cars make it cheaper to move people around cities, the value of inner-city land will fall simply because their proximity to the action has diminished.

With drones and driverless cars, it will be easier to bring something in on the just-in-time basis rather than have it on hand as inventory or within walking distance because traffic congestion makes it too slow to call it up from the suburbs through the conventional commercial transport.

But we live in a world of trade-offs. More people may want to move into the city because it’s so much easier to move around and call things up by drone, driverless car and the share economy, so this may intensify agglomeration effects and increased land prices. Another big day out for the two handed economist.

Creative destruction in recorded music sales

16 May 2015 1 Comment

in entrepreneurship, industrial organisation, Music, survivor principle Tags: creative destruction, entrepreneurial alertness

CHART: Recorded Music Sales Have Collapsed and Were At a 40+ Year Low in 2013 http://t.co/p0zIdbutSx—

Mark J. Perry (@Mark_J_Perry) May 07, 2015

The Rise and Rise of the Super Working Rich

15 May 2015 1 Comment

in economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, human capital, industrial organisation, labour economics, occupational choice, property rights, survivor principle, theory of the firm Tags: entrepreneurial alertness, Eugene Fama, Leftover Left, separation of ownership and control, super-rich, superstar wages, superstars, top 1%, Twitter left, working rich

The rise of the rentiers is nothing new. What is new is the degree of financial globalization and liberalization that has supercharged the fortunes of the super-wealthy even beyond robber baron levels. But it’s no mystery how to reverse this. It’s a matter of setting better rules for markets and taxing earners at the top a bit more.

In the course of a deranged rant against the entrepreneurs in society, the Atlantic collected an excellent set of information suggesting that the working rich have replaced rentiers as the super-rich. Rentiers are the idle rich. A rentier is a person or entity receiving income derived from patents, copyrights, interest, etc.

In The Evolution of Top Incomes: A Historical and International Perspective (NBER Working Paper No. 11955), Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez concluded that:

While top income shares have remained fairly stable in Continental European countries or Japan over the past three decades, they have increased enormously in the United States and other English speaking countries.

This rise in top income shares is not due to the revival of top capital incomes, but rather to the very large increases in top wages (especially top executive compensation). As a consequence, top executives (the “working rich”) have replaced top capital owners at the top of the income hierarchy over the course of the twentieth century…

The Twitter Left claim that the surge in top compensation in the United States is attributable to an increased ability of top executives to set their own pay and to extract rents at the expense of shareholders. Obviously, from the chart below the pay the top 0.1% goes up and down with the share market. Top wages do not seem to have any independent power to dupe shareholders into overpaying them in bad times.

Xavier Gabaix and Augustin Landier found back in 2008 that what a major company’s CEO earns is directly proportional to the size of the firm that they are responsible for running. Executive compensation closely track the evolution of average firm value. During 2007 – 2009, firm value decreased by 17%, and CEO pay by 28%. During 2009-2011, firm value increased by 19% and CEO pay by 22%.

Xavier Gabaix and Augustin Landier also found that compensation for executives has risen with the market capitalization. From 1980 to 2003, the average value of the top 500 companies rose by a factor of six. Two commonly used indexes of chief executive compensation show close to a proportional six-fold matching increase.

Better executive decisions create more economic value. If the number of big companies is greater than the number of good chief executives, competitive bidding will push up executive pay to reflect the value of the talent that is available.

What happens to share prices when there is a surprise CEO resignation? Up or down? Apple went up and down in billions on news of Steve Jobs’ health.

When Hewlett Packard’s CEO Mark Hurd resigned unexpectedly, the value of HP stock dropped by about $10 billion! This makes his $30 million in annual compensation a bargain for shareholders. The fall in share price represents the difference between what the market expected from Hurd as Hewlett Packard’s CEO and what the market expects from his successor. Was Hurd under-paid?

There is an easy way to test for whether top executives cheat public shareholders. Compare the pay of large private companies, and public companies with a large or a few share holders, with public companies with diffuse share holdings. Private equity typically also pay its top executives very well, even though the capacity to dupe public shareholders are not a factor.

The burst of takeovers and leverage buyouts in the 1980s were very much driven by opportunities to profit from reducing corporate slack and downsizing flabby corporate headquarters of large publicly listed companies.

The response of the Left over Left of the day was support regulation to stop these mergers and takeovers rather than applauding them as giving lazy capitalists their comeuppance. This regulation undermined the market the corporate control rather than strengthened it as Michael Jensen explains:

This political activity is another example of special interests using the democratic political system to change the rules of the game to benefit themselves at the expense of society as a whole.

In this case, the special interests are top-level corporate managers and other groups who stand to lose from competition in the market for corporate control. The result will be a significant weakening of the corporation as an organizational form and a reduction in efficiency.

Central to the hypothesis of the Twitter Left of CEOs overpaying themselves is there is free cash within the business they pocket in pay rises, fringe benefits and lavished corporate headquarters rather than pay out in dividends or invest in profitable investments.

The interests and incentives of managers and shareholders frequently conflict over the optimal size of the firm and the payment of free cash to shareholders. What to pay the top executives is a minor manifestation of this common entrepreneurial difference of opinion the future of the business.

These conflicts in entrepreneurial judgements are severe in firms with large free cash flows–more cash than profitable investment opportunities. Jensen defines free cash flow as follows:

Free cash flow is cash flow in excess of that required to fund all of a firm’s projects that have positive net present values when discounted at the relevant cost of capital. Such free cash flow must be paid out to shareholders if the firm is to be efficient and to maximize value for shareholders.

Payment of cash to shareholders reduces the resources under managers’ control, thereby reducing managers’ power and potentially subjecting them to the monitoring by the capital markets that occurs when a firm must obtain new capital. Financing projects internally avoids this monitoring and the possibility that funds will be unavailable or available only at high explicit prices.

Michael Jensen developed a theory of mergers and takeovers based on free cash flows that explains:

- the benefits of debt in reducing agency costs of free cash flows,

- how debt can substitute for dividends,

- why diversification programs are more likely to generate losses than takeovers or expansion in the same line of business or liquidation-motivated takeovers,

- why bidders and some targets tend to perform abnormally well prior to takeover.

Michael Jensen noted that free cash flows allowed firms’ managers to finance projects earning low returns which, therefore, might not be funded by the equity or bond markets. Examining the US oil industry, which had earned substantial free cash flows in the 1970s and the early 1980s, he wrote that:

[the] 1984 cash flows of the ten largest oil companies were $48.5 billion, 28 percent of the total cash flows of the top 200 firms in Dun’s Business Month survey.

Consistent with the agency costs of free cash flow, management did not pay out the excess resources to shareholders. Instead, the industry continued to spend heavily on [exploration and development] activity even though average returns were below the cost of capital.

Jensen also noted a negative correlation between exploration announcements and the market valuation of these firms—the opposite effect to research announcements in other industries. Not surprisingly, after a successful corporate takeover, there is major changes to realise the untapped benefits they saw in the company that the incumbent management were not seizing capturing:

Corporate control transactions and the restructurings that often accompany them can be wrenching events in the lives of those linked to the involved organizations: the managers, employees, suppliers, customers and residents of surrounding communities.

Restructurings usually involve major organizational change (such as shifts in corporate strategy) to meet new competition or market conditions, increased use of debt, and a flurry of recontracting with managers, employees, suppliers and customers.

All modern theories of the focus in part or in full on reducing opportunistic behaviour, cheating and fraud in employment and commercial relationships. The market the corporate control, and mergers and takeovers realise large benefits from displacing underperforming manager teams. Premiums in hostile takeover offers historically exceed 30 percent on average. Acquiring-firm shareholders on average earn about 4 percent in hostile takeovers and roughly zero in mergers.

In terms of corporate control, Eugene Fama divides firms into two types: the managerial firm, and the entrepreneurial firm.

The entrepreneurial firms are owned and managed by the same people (Fama and Jensen 1983b). Mediocre personnel policies and sub-standard staff retention practices within entrepreneurial firms are disciplined by these errors in judgement by owner-managers feeding straight back into the returns on the capital that these owner-managers themselves invested. Owner-managers can learn quickly and can act faster in response the discovery of errors in judgement. The drawback of entrepreneurial firms is not every investor wants to be hands-on even if they had the skills and nor do they want to risk being undiversified.

The owners of a managerial firm advance, withdraw, and redeploy capital, carry the residual investment risks of ownership and have the ultimate decision making rights over the fate of the firm (Klein 1999; Foss and Lien 2010; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Jensen and Meckling 1976).

Owners of a managerial firm, by definition, will delegate control to expert managerial employees appointed by boards of directors elected by the shareholders (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b). The owners of a managerial firm will incur costs in observing with considerable imprecision the actual efforts, due diligence, true motives and entrepreneurial shrewdness of the managers and directors they hired (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983b).

Owners need to uncover whether a substandard performance is due to mismanagement, high costs, paying the employees too much or paying too little, excessive staff turnover, inferior products, or random factors beyond the control of their managers (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983b, 1985).

Many of the shareholders in managerial firms have too small a stake to gain from monitoring managerial effort, employee performance, capital budgets, the control of costs and the stinginess or generosity of wage and employment policies (Manne 1965; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Williamson 1985; Jensen and Meckling 1976). This lack of interest by small and diversified investors does not undo the status of the firm as a competitive investment nor introduce slack in the monitoring of payments to top executives.

Large firms are run by managers hired by diversified owners because this outcome is the most profitable form of organisation to raise capital and then find the managerial talent to put this pool of capital to its most profitable uses (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b, 1985; Demsetz and Lehn 1985; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988).

More active investors will hesitate to invest in large managerial firms whose governance structures tolerate excessive corporate waste and do not address managerial slack and and overpaid executives. Financial entrepreneurs will win risk-free profits from being alert and being first to buy or sell shares in the better or worse governed firms that come to their notice.

The risks to dividends and capital because of manifestations of corporate waste, reduced employee effort, and managerial slack and aggrandisement in large managerial firms are risks that are well known to investors (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jenson 1983b). Corporate waste and managerial slack also increase the chances of a decline in sales and even business failure because of product market competition (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983b).

Investors will expect an offsetting risk premium before they buy shares in more ill-governed managerial firms. This is because without this top-up on dividends, they can invest in plenty of other options that foretell a higher risk-adjusted rate of return. The discovery of monitoring or incentive systems that induce managers to act in the best interest of shareholders are entrepreneurial opportunities for pure profit (Fama and Jensen 1983b, 1985; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988; Demsetz 1983, 1986; Demsetz and Lehn 1985; Demsetz and Villalonga 2001).

Investors will not entrust their funds to who are virtual strangers unless they expect to profit from a specialisation and a division of labour between asset management and managerial talent and in capital supply and residual risk bearing (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). There are other investment formats that offer more predictable, more certain rate of returns.

Competition from other firms will force the evolution of devices within the firms that survive for the efficient monitoring the performance of the entire team of employees and of individual members of those teams as well as managers (Fama 1980, Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). These management controls must proxy as cost-effectively as they can having an owner-manager on the spot to balance the risks and rewards of innovating.

The reward for forming a well-disciplined managerial firm despite the drawbacks of diffuse ownership is the ability to raise large amounts in equity capital from investors seeking diversification and limited liability (Demsetz 1967; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983b; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). Portfolio investors may know little about each other and only so much about the firm because diversification and limited liability makes this knowledge less important (Demsetz 1967; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988).

It is unwise to suppose that portfolio investors will keep relinquishing control over part of their capital to virtual strangers who do not manage the resources entrusted to them in the best interests of the shareholders (Demsetz 1967; Williamson 1985; Fama 1980, 1983b; Alchian and Woodward 1987, 1988).

Managerial firms who are not alert enough to develop cost effective solutions to incentive conflicts and misalignments will not grow to displace rival forms of corporate organisation and methods of raising equity capital and loans, allocating legal liability, diversifying risk, organising production, replacing less able management teams, and monitoring and rewarding employees (Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b; Fama 1980; Alchian 1950).

Entrepreneurs will win profits from creating corporate governance structures that can credibly assure current and future investors that their interests are protected and their shares are likely to prosper (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b, 1985; Demsetz 1986; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). Corporate governance is the set of control devices that are developed in response to conflicts of interest in a firm (Fama and Jensen 1983b).

At bottom, the private sector is highly successful designing forms of organisation that allow large sums of money, billions of dollars to be raised in the capital market and entrusted to management teams.

via The Rise and Rise of the Super-Rich – The Atlantic and How the Richest 400 People in America Got So Rich – The Atlantic.

Recent Comments