The Supreme Court should grant certiorari on this case. There is a clear conflict between several federal court rulings, specifically and most clearly the Second Circuit’s dismissal of New York City’s virtually identical lawsuit in 2021and the ruling by the Hawaii Supreme Court. Both court rulings reveal a conflict on the issue of whether federal law precludes claims brought under state law and whether a given state may apply its laws to address purported injuries caused by emissions from another state. Moreover, the Hawaii Supreme Court decision clearly is incorrect: Interstate emissions, international emissions, and negotiations with foreign governments inherently are issues for the federal government to address.

The Interests of the U.S. and the Honolulu Climate Case Before the U.S. Supreme Court

The Interests of the U.S. and the Honolulu Climate Case Before the U.S. Supreme Court

12 Jan 2025 1 Comment

in economics of climate change, energy economics, environmental economics, environmentalism, global warming, law and economics, politics - USA, property rights Tags: climate alarmism, federalism

Energy, Business Groups Ask Supreme Court To Stop California From Forcing EVs On the Rest of America

09 Jul 2024 Leave a comment

in economics of regulation, energy economics, environmental economics, global warming, law and economics, politics - USA Tags: constitutional law, federalism

Numerous trade associations are asking the Supreme Court to review a lower court’s decision that effectively allowed California to push electric vehicles (EVs) on the rest of the U.S.

Energy, Business Groups Ask Supreme Court To Stop California From Forcing EVs On the Rest of America

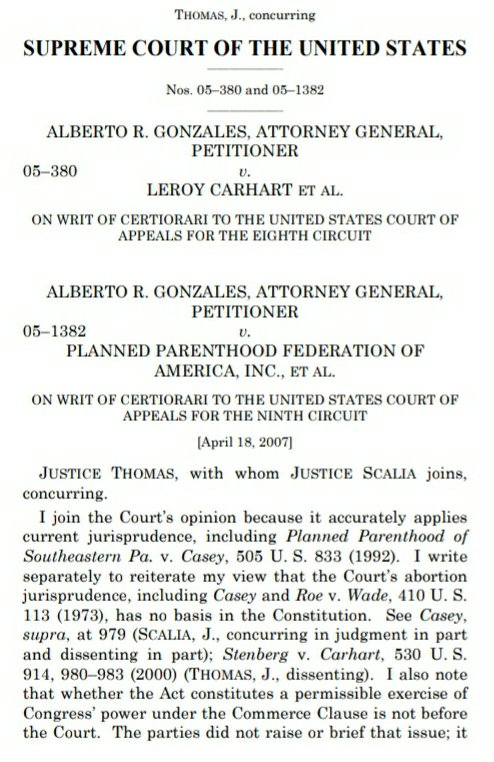

Scalia and Thomas on a federal abortion ban

13 May 2022 Leave a comment

in comparative institutional analysis, constitutional political economy, discrimination, gender, law and economics Tags: abortion rights, constitutional law, federalism

Why Is Marijuana Legal in Some States and Not Others?

24 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, economics of crime, economics of regulation, health economics, law and economics Tags: federalism, war on drugs

@DavidLeyonhjelm on deregulating the Australian labour market

17 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in applied price theory, economic history, economics of regulation, industrial organisation, job search and matching, labour economics, minimum wage, survivor principle, unions Tags: Australia, employment law, employment protection law, federalism, labour market deregulation, labour market regulation, union power, unions

Puerto Rico’s economy can’t handle the federal minimum wage

11 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, Federalism, income redistribution, labour economics, labour supply, minimum wage, politics - USA, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: federalism, living wage, Puerto Rico, sovereign default

Puerto Rico's economy can't handle the federal minimum wage. bit.ly/1IEJIEi http://t.co/D3mzOmlnJa—

Manhattan Institute (@ManhattanInst) July 07, 2015

If the right people don’t have power – Yes Prime Minister

03 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, economics of bureaucracy, Public Choice, TV shows Tags: devolution, federalism, Yes Prime Minister

The economics of federalism: states as decentralized competitors and political markets

08 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

New drug lags versus laboratory federalism

07 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, health economics Tags: drug lags, federalism, laboratory federalism

How to refute the case for a minimum wage when genuinely calling for a smarter federal minimum wage

30 Jun 2014 1 Comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, labour economics, minimum wage Tags: federalism, george stigler, minimum wage, monopsony

What if minimum wage rates could somehow be tied to specific locations as suggested by former White House economist Jared Bernstein puts it in an essay in the New York Times:

When we adjust a national minimum wage of $10.10 for regional differences, these are the amounts you’d need to have the same buying power: $11.94 in Washington, D.C., and $11.40 in California, but only $8.90 in Alabama and $9.08 in Kansas.

And of course, prices vary within states as well. In the New York City area, it would take $12.34 to meet the national buying power of $10.10; upstate around Buffalo, you’d need only $9.47. In the Los Angeles area, it would take $11.94; go up north a bit to Bakersfield, where prices are closer to the national average, and it’s $9.83.

To repeat what George Stigler said on the unsuitability of a nation-wide minimum wage in 1946 when there was monopsony, and therefore a small minimum wage increase is less likely to result in a reduction in employment:

If an employer has a significant degree of control over the wage rate he pays for a given quality of labour, a skilfully-set minimum wage may increase his employment and wage rate and, because the wage is brought closer to the value of the marginal product, at the same time increase aggregate output…

This arithmetic is quite valid but it is not very relevant to the question of a national minimum wage. The minimum wage which achieves these desirable ends has several requisites:

1. It must be chosen correctly… the optimum minimum wage can be set only if the demand and supply schedules are known over a considerable range…

2. The optimum wage varies with occupation (and, within an occupation, with the quality of worker).

3. The optimum wage varies among firms (and plants).

4. The optimum wage varies, often rapidly, through time.

A uniform national minimum wage, infrequently changed, is wholly unsuited to these diversities of conditions

A smarter federal minimum wage is a federal minimum wage of zero. Let each state and city set a minimum wage in accordance with its own economic conditions and the blackboard economics of monopsony and competition in the labour market.

As soon as you concede that there is not one single national labour market, other concessions must be made. This slippery slope includes that the monopsony power of employers might vary from state to state, city to city, and local labour market from local labour market.

Even a state or city minimum wage regulator would have to pretend to know an immense amount of information about the labour market with most of this information in a tacit form that cannot be summarised in statistics or other decision aids for regulators. As Hayek reminded in his classic in 1945 on The Use of Knowledge in Society:

the fact that the sort of knowledge with which I have been concerned is knowledge of the kind which by its nature cannot enter into statistics and therefore cannot be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form.

The statistics which such a central authority would have to use would have to be arrived at precisely by abstracting from minor differences between the things, by lumping together, as resources of one kind, items which differ as regards location, quality, and other particulars, in a way which may be very significant for the specific decision.

It follows from this that central planning based on statistical information by its nature cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place and that the central planner will have to find some way or other in which the decisions depending on them can be left to the "man on the spot."

The merits of federalism

29 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in Federalism, Public Choice Tags: federalism

- A divided government is a weak government.

- One great feature of the federal system is that we can try different policies in different states and see what works and what doesn’t.

- The laws of each state can more closely reflect local public opinion.

- The will of the people is constantly tested and re-measured in a federal system: elections at one level or another every year contested on local and national issues.

- People vote more often for different policy packages, rather than occasionally for a few up and down choices.

- The will of the people is constantly tested and re-measured in a federal system: elections at one level or another every year contested on local and national issues.

After 15 years of Maggie Thatcher, good and hard, British Labor reconsidered devolution because a federal state slows the impassioned majority down.

Who do members of parliament represent?

28 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, Federalism, James Buchanan, Joseph Schumpeter, Public Choice Tags: consititutional design, Edmund Burke, federalism, James Madison, Jospeh Schumpeter, JS Mill, theories of representation

The theoretical literature on political representation focused on whether representatives should act as delegates or as trustees. James Madison articulated a delegate conception of representation. Representatives who are delegates simply follow the expressed preferences of their constituents.

The classical liberals of the 18th century were highly sceptical about the capability and willingness of politics and politicians to further the interests of the ordinary citizen, and thought the political direction of resource allocation retards rather than facilitates economic progress.

Governments were considered to be institutions to be protected from but made necessary by the elementary fact that all persons are not angels. Constitutions were a means to constrain collective authority. The problem of constitutional design was ensuring that government powers would be effectively limited.

- Sovereignty was split among several levels of collective authority; federalism was designed to allow for a deconcentration or decentralization of coercive state power.

- At each level of authority, separate branches of government were deliberately placed in continued tension, one with another.

- The dominant legislative branch was further restricted by the constitutional establishment of two houses bodies, each of which was elected on a separate principle of representation.

These constitutions were designed and put in place by the classical liberals to check or constrain the power of the state over individuals. The motivating force was never one of making government work better or even of insuring that all interests were more fully represented.

Members of parliament as trustees are representatives who follow their own understanding of the best action to pursue in another view. As Edmund Burke wrote:

Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests; which interests each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates; but parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole; where, not local purposes, not local prejudices ought to guide, but the general good, resulting from the general reason of the whole.

You choose a member indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of parliament. …

Our representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion.

Burke does not seem to be a fan of federalism and vote trading to protect minorities. Madison liked conflict and tension as a constraint of power and the size of government.

Schumpeter disputed that democracy was a process by which the electorate identified the common good, and that politicians carried this out:

• The people’s ignorance and superficiality meant that they were manipulated by politicians who set the agenda.

• Democracy is the mechanism for competition between leaders.

• Although periodic votes legitimise governments and keep them accountable, the policy program is very much seen as their own and not that of the people, and the participatory role for individuals is usually severely limited.

Modern democracy is government subject to electoral checks. John Stuart Mill had sympathy for this view that parliaments are best suited to be places of public debate on the various opinions held by the population and to act as watchdogs of the professionals who create and administer laws and policy:

Their part is to indicate wants, to be an organ for popular demands, and a place of adverse discussion for all opinions relating to public matters, both great and small; and, along with this, to check by criticism, and eventually by withdrawing their support, those high public officers who really conduct the public business, or who appoint those by whom it is conducted

Representative democracy has the advantage of allowing the community to rely in its decision-making on the contributions of individuals with special qualifications of intelligence or character. Representative democracy makes a more effective use of resources within the citizenry to advance the common good.

Recent Comments