The NZ Herald’s Editor has declared its journalists will be promoted or fired on the basis of factors like how many clicks they get on their articles. Yes, the Herald is now officially “click bait”. We’re trying to avoid the mistake of writing shallow nonsense at this Blog. So on that note, here’s a somewhat…

Does the Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle mean National’s Foreign Investment Ambitions Won’t Raise NZ Productivity?

Does the Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle mean National’s Foreign Investment Ambitions Won’t Raise NZ Productivity?

26 Feb 2025 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, econometerics, economic history, financial economics, history of economic thought, international economics, macroeconomics, politics - New Zealand Tags: foreign investment

Walter Block defends multinational corporations in developing countries

18 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, growth disasters, growth miracles, industrial organisation, international economics, labour economics, labour supply Tags: foreign direct investment, foreign investment, multinational corporations, Walter Bloch

How Taxes Affect Investment Decisions For Multinational Firms

11 May 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: company tax rates, foreign investment, multinational corporations, tax competition

How Taxes Affect Investment Decisions For Multinational Firms onforb.es/1Oe5lKu by @ErikCederwall http://t.co/BduZZbHs2n—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) April 15, 2015

Why is NZ so hostile to foreign investment, 32nd in the Index of Economic Freedom 2015? USA is 66th!

02 Feb 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, international economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: bootleggers and baptists, foreign direct investment, foreign investment, free trade, Index of Economic Freedom

Source: 2015 Index of Economic Freedom

According to the Index of Economic Freedom 2015, in New Zealand

Foreign investment is welcomed, but the government may screen some large investments.

There was a major review of New Zealand foreign investment regulations about 10 years ago. The purpose of that review commissioned by the Labour government’s Minister of Finance, Dr Michael Cullen, was to deregulate the regulation of foreign investment in New Zealand.

At the time,under the Overseas Investment Act, the Minister of Finance could refuse permission to any investment. Australia’s current overseas investment regulations are the same. The federal treasurer may reject foreign investment proposals on the basis of an open-ended definition of national interest.

The last time that foreign investors had been refused permission to invest in New Zealand was in the early 1980s under then National Party Government Prime Minister Robert Muldoon. In a fit of pique, he refused permission to an Australian investor.

The revised foreign investment regulations limits the ability of government to reject foreign investors to narrow criteria such as the acquisition of sensitive land and large New Zealand companies. As part of this theme that foreign acquisitions of land was the main policy concern regarding foreign investment, the administration of the foreign investment regulations was moved out of a Overseas Investment Commission housed at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to the very low key Land Information Office:

The Overseas Investment Office (OIO) assesses applications from overseas investors seeking to invest in sensitive New Zealand assets – being ‘sensitive’ land, high value businesses (worth more than $100 million) and fishing quota.

Naturally, subsequent to this genuine attempt by the Labour government of 10 years ago to deregulate foreign investment regulation, a number of investments have been refused since then often on the pretext that some part of the investment acquired sensitive coastal land door or rural land. The criteria for regulating foreign investment is as follows:

As regards the criteria relating to the relevant “overseas person”, the OIO needs to be satisfied that:

- the “overseas person” has demonstrated financial commitment to the investment; and

- the “overseas person” or (if that person is not an individual) the individuals with ownership and control of the overseas person (such as the shareholders and directors of the overseas purchaser):

- have the business experience and acumen relevant to that investment;

- are of good character; and

- are not prohibited from entering New Zealand by reason of sections 15 or 16 of the Immigration Act 2009 (e.g. persons who have been imprisoned for certain periods of time).

As regards the criteria relating to the particular investment, the OIO needs to be satisfied that the overseas investment will, or is likely to, benefit New Zealand (or any part of it or group of New Zealanders). When considering this, the OIO has a range of factors that it must consider (including, for example, whether the investment will create new job opportunities, introduce new technology or business skills, advance a significant Government policy or strategy, or bring other consequential benefits to New Zealand).

The New Zealand Initiative recently reviewed this criteria for regulating overseas investment into New Zealand and found that:

the report finds that the criteria for approval do not test the economic benefit to New Zealanders, where sensitive land is sold to an overseas person not intending to live in New Zealand indefinitely.

Indeed, the criteria are unambiguously hostile, even excluding the gain to a New Zealand vendor. This opens the way for the imposition of approval conditions that could impose net costs on New Zealanders given the regime’s potentially adverse effects on land values

The regulation of foreign investment in other countries is much more specific about what it is trying to achieve,as New Zealand Initiative also noted in its recent review:

New Zealand’s comprehensive screening regime accounts for our poor international ranking in the OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.

Most other countries focus their regimes more narrowly on national security considerations, often relating to particularly sensitive industries or sectors.

The main reason the public supports foreign investment regulation is because the public doesn’t like foreigners, and politicians pander to that xenophobia. If foreign investment is reduced, more of total investment spending has to be funded from domestic saving.

Access to foreign savings – trade in savings – allows investment to be made sooner, consumption to be smoothed over hiatuses such as recessions, and consumption to be bought forward in the light of better times such higher output and higher future incomes as because of foreign investment.The

The large national gains from foreign capital inflows is not part of that debate. A recent review of the gains from foreign capital inflows to New Zealanders found access to foreign saving led to national income per head, net of the servicing cost of foreign capital:

- average income gains of $2,600 per worker arising on a cumulative basis from capital inflow over the period 1996 – 2006; and

- growth in the value of New Zealand’s assets has greatly exceeded the rise in external liabilities to the extent that national wealth per head has risen by $14,000 in 2007 prices between 1996 and 2006.

You can’t let facts bugger a good story.

The foreign investment is in response to the high returns in the local market and the inflow of foreign capital will continue until local rates of return match those in other countries. Equalisation of risk-adjusted rate of returns is central to the operation of capital markets.

Stopping this process of equalisation of returns on capital through regulation only benefits the capitalists inside the country because the curbing of foreign investment stops rates of return falling to those overseas. Foreign investment regulation reduces the wages of New Zealand workers because they have less capital and fewer modern technologies to work with.

Fortunately, local capitalists can work in league with economic populists on the left and the right and the anti-foreign bias of the voting public to make it more difficult for foreign investors to come to New Zealand and drive down the profits of New Zealand capitalists. Who gains from that? As Paul Krugman said:

The conflict among nations that so many policy intellectuals imagine prevails is an illusion; but it is an illusion that can destroy the reality of mutual gains from trade.

The current-account deficit is a false problem

01 Jul 2014 1 Comment

in applied welfare economics, international economics Tags: capital account surpluses, current account deficits, foreign investment, international trade in savings, John Cowperthwaite

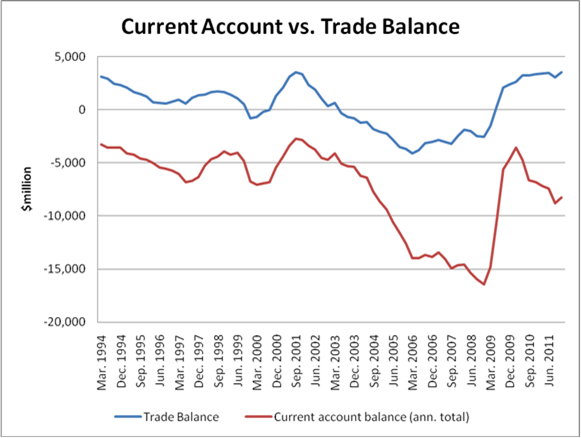

The current account balance equals net foreign investment. When net foreign investment is positive, the current account is in deficit. The current account balance is the result of the international trade in savings and the relative rewards and incentives of investing at home or abroad:

- The current account is in surplus when national saving is greater than net domestic investment; and

- The current account is in deficit when national saving is less than net domestic investment.

New Zealand can import more than it exports courtesy of this foreign investment.

- The difference between exports and imports, or net exports, is the trade balance.

- But for net foreign investment, the trade balance would have to always balance.

For most of the last 20-years, exports have been the same as imports, more or less, so the New Zealand current account deficit has little to do with the level of exports or imports.

A current account could be called a capital account surplus, but this label lacks that certain demonic ring the media laps up. Deficits are bad, surpluses are good. How can a surplus be bad? Who wants to cut a surplus?

John Cowperthwaite solved Hong Kong’s current account problems by not collecting trade statistics. His concern was:

If I let them compute those statistics, they’ll want to use them for planning.

Cowperthwaite refused to collect economic statistics

for fear that I might be forced to do something about them

If New Zealand did not collect trade statistics, would anyone be the worse off? How would we notice?

People knew that unemployment and inflation were a problem long before statistics agencies descended upon us.

The better solutions to unemployment and inflation are rules-based and were developed again long before statistics were collected.

Rules based policy regimes that attempt to stabilise unemployment and inflation often reject discretionary responses to the latest statistical releases.

Indeed, the main focus of rules based policy regimes is to prevent monetary and fiscal policy from becoming an independent source of instability. The secret of inflation targeting is to do as little as possible and not make things worse by doing much more that keeping monetary supply growth in check.

What is the welfare cost of a current account deficit and how does it compare?

- Welfare cost of inflation of 10% is maybe 1-2% of national income; and

- The annual welfare cost of the post-war business cycle is about 1% of national income.

People apparently fear the current account because it may lead to recessions and inflation. But the current account must be a small component of the factors contributing to the welfare cost of inflation and the annual welfare cost of the post-war business cycle.

There are a large number of other factors that cause recessions and and one factor that causes inflation. These must get their share of the 1-2% of national income that is the welfare cost of post-war business cycles and inflation of 10%. Adding up constraints mean that the welfare cost of the current account deficit, if there is such a welfare cost, must be small.

Scobie, Zhang and Makin (2008) found average income gains of $2,600 per New Zealand worker on a cumulative basis from capital inflows over the period 1996 – 2006. International capital mobility allows New Zealand to fund additional investment from external sources which raises wages in New Zealand because there is more technology and capital per worker in New Zealand. To the extent that foreign investment occurs, it raises the amount of capital in a country, driving wages up and profits down.

The current account reflects the relative returns of investing at home and abroad and any consumption smoothing. People save and borrow to smooth out consumption during any temporary ups and downs in their annual incomes.

The current-account balance typically gets worse—moves into deficit—in good times. Reason for this is in good times, people anticipate higher permanent incomes in the future and start spending now before the higher income actually arrives.

New Zealand and Australia based their prosperity on borrowing in anticipation of future increases in production based on exploiting the ample land and natural resources in New Zealand and Australia. This increase of wealth could be spread out over many periods including before it actually arrived because of the ability to borrow in the international credit markets in anticipation of permanently higher future incomes.

Who gains from anti-imperialism and opposition to foreign investment?

21 May 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, David Friedman, development economics, Public Choice Tags: bootleggers and baptists, expressive voting, foreign investment, imperialism, marxist fallacies

Much more commonly, [economic imperialism] is used by Marxists to describe–and attack–foreign investment in “developing” (i.e., poor) nations.

The implication of the term is that such investment is only a subtler equivalent of military imperialism–a way by which capitalists in rich and powerful countries control and exploit the inhabitants of poor and weak countries.

There is one interesting feature of such “economic imperialism” that seems to have escaped the notice of most of those who use the term.

Developing countries are generally labour rich and capital poor; developed countries are, relatively, capital rich and labour poor. One result is that in developing countries, the return on labour is low and the return on capital is high–wages are low and profits high. That is why they are attractive to foreign investors.

To the extent that foreign investment occurs, it raises the amount of capital in the country, driving wages up and profits down.

The effect is exactly analogous to the effect of free migration. If people move from labour-rich countries to labour-poor ones, they drive wages down and rents and profits up in the countries they go to, while having the opposite effect in the countries they come from.

If capital moves from capital-rich countries to capital-poor ones, it drives profits down and wages up in the countries it goes to and has the opposite effect in the countries it comes from.

The people who attack “economic imperialism” generally regard themselves as champions of the poor and oppressed.

To the extent that they succeed in preventing foreign investment in poor countries, they are benefiting the capitalists of those countries by holding up profits and injuring the workers by holding down wages.

It would be interesting to know how much of the clamour against foreign investment in such countries is due to Marxist ideologues who do not understand this and how much is financed by local capitalists who do.

David D. Friedman

Opposition to immigration might protect the wages of local workers. Opposition to foreign investment might increase the profits of local capitalists.

How does more competition help the local capitalists? The foreign investment is in response to the high returns in the local market and that inflow of foreign capital will continue until local rates of return match those in other countries.

Equalisation of risk-adjusted rate of returns is central to the operation of capital markets.

Stopping this process of equalisation through regulation only benefits the capitalists inside the country. It reduces the wages of workers because they have less capital and fewer modern technologies to work with.

Recent Comments