Keep your eye on what happens to consumers alert: Murray Rothbard on dumping

01 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

Rate this:

Preferences are demonstrated through choices – nothing more and nothing less

04 Sep 2014 Leave a comment

Rate this:

Moral and other philosophical values had to be given greater consideration in economic analysis

14 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

Rate this:

Murray Rothbard (1982) on Israeli settlements in the West Bank

10 Aug 2014 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in International law, libertarianism, Murray Rothbard, war and peace Tags: Israel, Murray Rothbard, revanchism, West Bank

To be fair, on the State of Israel, Murray Rothbard was an anti-Zionist warmongering revanchist. In 1969, for example, he argued that there are some wars that can be blamed more on one state than another and that the Israelis were to blame for most of the Israeli-Arab wars.

Rate this:

Palestinian revanchism is a recipe for endless wars

06 Aug 2014 8 Comments

by Jim Rose in laws of war, Murray Rothbard, war and peace Tags: Gaza Strip, Hamas, irredentism, Murray Rothbard, revanchism, warmongering

Why are borders in 1861, 1919, 1945, 1948, 1956 or 1967 or any other time morally superior?

Palestinian revanchism is a recipe for endless wars. Revanchism is the desire to reverse territorial losses.

Revanchism is linked with irredentism, the conception that a part of the cultural and ethnic nation remains “unredeemed” outside the borders of its appropriate nation-state.

• A return of German revanchism would plunge Europe back into war as Germany marched to reclaim Western Poland and the Sudetenland lost after the massive ethic cleansing in 1945 and the moving of Poland 1/3rd to the left after Potsdam.

• The Balkans and Eastern Europe would be plunged into war to revise the 1945 and the 1919 boundaries.

• Irish revanchism and irredentism over protestant Northern Ireland led to war from 1922 onwards.

The just war doctrine of the Catholic Church found in the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, which is a convenient summary as any on what is and is not a just war, lists four strict conditions for legitimate defence by military force:

- the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain;

- all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be impractical or ineffective;

- there must be serious prospects of success;

- the use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated (the power of modern means of destruction weighs very heavily in evaluating this condition).

Hamas does not have any serious prospects of success in its attacks on Israel. Therefore any military action by Hamas is an unjust war

Rate this:

Why is Austrian business cycle theory held to such a high-bar?

14 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in Austrian economics, macroeconomics Tags: Austrian business cycle theory, Murray Rothbard, rational expectations

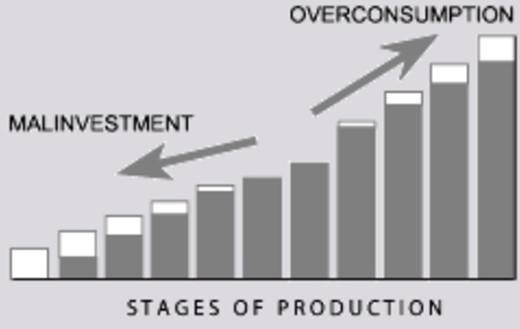

I find it surprising that so many concentrate on rational expectations when discussing Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT). Is Austrian business cycle theory the only modern business cycle theory that must reach such a high bar?

Many modern business cycle theories build on information costs and learning and explain that people make forecasting errors because of noisy information, and repeated monetary shocks keeping up this confusion.

A good general explanation of misperceptions theories of business cycle is in Alchian and Allen (1967), which Murray Rothbard called a brilliant textbook. The business cycle is not based on money illusion or on systematic mistakes.

People take time to acquire the necessary information to interpret what has shocked the economy and what these changes mean for them. Additional shocks complicate this learning so there are more errors and confusion continues to affect market choices. Learning is neither instantaneous nor is the requisite information free to collate. People must make do with the incomplete knowledge they have and make choices about market signals that might be spurious or be meaningful signs of change.

Mises, Hayek, and Rothbard all noted in the collection edited by Garrison, for example, that a one-shot monetary shock would be soon uncovered by entrepreneurs, the malinvestments quickly reversed, and the boom would bust. Monetary shock after monetary shock require repeated entrepreneurial revisions and it will take a long time for entrepreneurs to catch up. This is also in Alchian and Allen.

Rothbard (MES pp. 1002-1005) discusses one-time versus repeated and increasingly large in size monetary shocks as the basis for booms and the reasons for the on-going deception of entrepreneurs. The shocks must increase in size to keep injecting more unanticipated noise into monetary and entrepreneurial calculations.

ABCT proposes a more complicated signal extraction problem than in say the Lucas-Phelps islands model. Dispersed and slowly unfolding information must be produced as each new monetary shock ripples its own unique way across the economy, passing through different hands each time. Only slowly does the requisite knowledge about the relative prices effects of each new monetary shock emerge as the result of market interactions and become open to entrepreneurial discovery.

What is perhaps dismissed too easily by Rothbard (but not Mises) is that under a gold standard, increases in the output of gold mining can be well forecasted by entrepreneurs. Rothbard’s best ground is when he notes that "the credit expansion tampered with all their [entrepreneurs’] moorings." A stop-go monetary policy is by definition unpredictable. Gold output fluctuations are irregular but usually small. A unique contribution of ABCT is that the longer the boom, the deeper the bust.

Rate this:

Every time the Fed tightens the money supply, interest rates rise (or fall); every time the Fed expands the money supply, interest rates rise (or fall).

08 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in macroeconomics, Murray Rothbard Tags: inflation, interest rates, Murray Rothbard

The problem is that… there are several causal factors operating on interest rates and in different directions.

If the Fed expands the money supply, it does so by generating more bank reserves and thereby expanding the supply of bank credit and bank deposits. The expansion of credit necessarily means an increased supply in the credit market and hence a lowering of the price of credit, or the rate of interest. On the other hand, if the Fed restricts the supply of credit and the growth of the money supply, this means that the supply in the credit market declines, and this should mean a rise in interest rates.

And this is precisely what happens in the first decade or two of chronic inflation. Fed expansion lowers interest rates; Fed tightening raises them.

But after this period, the public and the market begin to catch on to what is happening. They begin to realize that inflation is chronic because of the systemic expansion of the money supply.

When they realize this fact of life, they will also realize that inflation wipes out the creditor for the benefit of the debtor. As creditors begin to catch on, they place an inflation premium on the interest rate, and debtors will be willing to pay it.

Hence, in the long run anything which fuels the expectations of inflation will raise inflation premiums on interest rates; and anything which dampens those expectations will lower those premiums. Therefore, a Fed tightening will now tend to dampen inflationary expectations and lower interest rates; a Fed expansion will whip up those expectations again and raise them.

There are two, opposite causal chains at work. And so Fed expansion or contraction can either raise or lower interest rates, depending on which causal chain is stronger.

Which will be stronger? There is no way to know for sure. Will In the early decades of inflation, there is no inflation premium; in the later decades, such as we are now in, there is. The relative strength and reaction times depend on the subjective expectations of the public, and these cannot be forecast with certainty

Rate this:

Recent Comments